TO MIMI AND DORON

The man of letters is the enemy of the world.

Charles Baudelaire

To describe the fatal character of contemporary things

the painter uses that most modern recoursesurprise.

Guillaume Apollinaire

CONTENTS

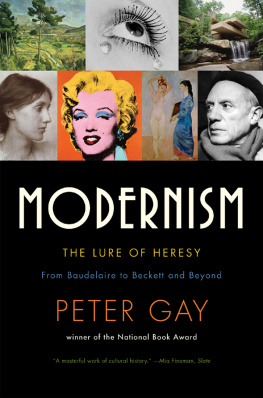

T HIS BOOK IS A STUDY OF MODERNISM, ITS RISE, TRIUMPHS, AND decline. As the reader will quickly discover, it is the work of a historian; I shall disregard chronology when I find that useful or necessary, but my dominant direction will be to move forward from past to present, from chapter to chapter, and within each chapter. It is a historians book, too, in that I have not stayed within the confines of formal analysis of novels and sculptures and buildings, but will, if briefly, place the works of modernists into the world in which they lived.

Yet the book is not a history of modernism, which, given the mass of available materials, would be almost unthinkable in a single volume, or else reduced to nothing better than a pile of thumbnail sketches. Where are William Faulkner and Saul Bellow among the novelists? William Butler Yeats and Wallace Stevens among the poets? Where are Francis Bacon and Willem de Kooning among the painters, and why have I said so little about Matisse, and then only as a sculptor? Was it reasonable to skip composers like Aaron Copland and Francis Poulenc, or Richard Neutra and Eliel Saarinen among the architects? Can I justly hope to cover path-breaking movie directors by confining myself to four of them? Where are topics like opera and photography? In a history, I would have had to find room for them all. But, as the introductory section, A Climate for Modernism, should make clear, I have looked for what modernists had in common, and the social conditions that would foster or dishearten them.

I have, then, treated painters and playwrights, architects and novelists, composers and sculptors as exemplars of indispensable elements in the modernist period. But I have aimed to make my choices, selective as they are, to add up to a usable definition of modernism, its scope, its limits, and its most characteristic expressions. I should emphasize at the outset that in making my selections I have not been guided by my political views, at least not consciously. I have after all provided detailed observations for such key modernists as the Fascist Knut Hamsun, the bigoted High Anglican T. S. Eliot, and the hysterical anti-feminist August Strindberg. I deplore their ideologies, but I found them vital witnesses. Yet, as I have said, the point of this study is not to compile an expansive catalog of all the strands and leading figures in modernism, but to examine their presence in culture and to discover, if possible, whether they coalesce to define a single cultural entity. My slogan has been that of the Founding Fathers: E pluribus unum .

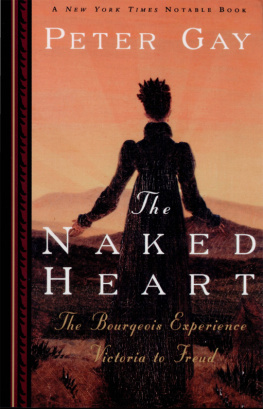

BUT WHERE IS FREUD? Does he not belong, after all, among the most dramatic of modernists? Certainly, when we assess Freuds taste, we must deny him that title. In art, music, and literature, he was a perfectly conservative bourgeois. He admired Ibsen but was silent about Strindberg; he liked among living novelists the skillful craftsman and socially sensitive but scarcely avant-garde John Galsworthy, and seems not to have known the novels of Virginia Woolf, even though she and her husband Leonard were his English publishers; the pictures on his walls reveal no sign of response to Austrian moderns like Klimt or Schiele, and his furniture shows that the experimental designs of Viennese modernists had made no inroads on him. His principled opposition to the received social and cultural attitudes of his class lay elsewhere.

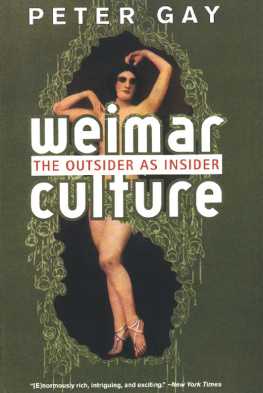

Indeed, when we note the reluctant, usually bitterly antagonistic reception of Freuds ideas across the twentieth century, especially on sexuality, his uncompromising role as a dissenter quickly becomes apparent. If much of the Freudian view of the human animal present and past appears to be fairly commonplace today, that is so because for a century much of the respectable world has made its progress toward him. It has adopted phrases from the psychoanalytic dictionarysibling rivalry, defensive maneuver, passive-aggressivewithout acknowledgment. Hence it is not far-fetched to describe the first set of sympathetic colleagues who began weekly meetings in Freuds Viennese apartment from 1902 on as an avant-garde in the healing professions, especially after that Wednesday group graduated to become the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association. It was, and remained, at war with conventional medicine and psychiatry, and was firmly led by a single, confident innovator. As we shall see, F. T. Marinetti, the dominant figure among the Futurists around the time of the First World War, and Andr Breton, among the Surrealists in the 1920s, occupied rather similar positions. They were the Freuds of their clans.

THE IMPACT OF FREUD S psychoanalytic theories on modern Western culture has not yet been fully mapped. Indirect as much of it was, it was certainly enormous, especially among educated bourgeois, whose tastes were also inextricably implicated in the origins and progress of modernism. Whether it is the matter of parents speaking to their children frankly about such delicate topics as where babies come from; a loosening of the meaning of family, so that unmarried couples living together are no longer shocking as they once were; a markedly growing acceptance by society for what used to be called perversions like homosexuality and lesbianism; a sharply increased awareness of the ravages that human aggressiveness can causesharply increased but, as recent history teaches only too painfully, not enough to influence policy; and other, similar cultural habits. This is not to deny that in some circles, the Freudian way of thinking remains as indigestible as it was a century ago.

But not, I must emphasize, for me. I am aware that there are still debatable, and still debated, clinical and theoretical issues in psychoanalytic thinking like the causes of dreams, the maturation of female sexuality, and the healing properties of the talking cure as against the ministrations of medication. But these are matters that, however they are eventually resolved, will not make Freuds (and his followers) ways of thinking about the mind, its functioning and malfunctioning, irrelevant. His view of human nature, to summarize it tersely, features placing mind into its natural world, which means that it is susceptible to causal laws, whether physiological or psychological; the devious, inadequately recognized activity of the dynamic unconscious; and the inescapable lasting discord between libido and aggression. The psychoanalytic technique of fostering free association in his patients was the equivalent of the Impressionist painter taking his easel out of doors or the modernist composer abandoning traditional key signatures. Freud, the self-declared scientist of the mind, was in sizable company in making contradictory feelingsambivalencecentral to his picture of the world. This tragic vision renders a life of conflict an essential element in historyincluding that of modernism.

Next page