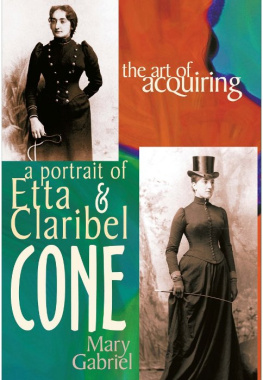

The Art of Acquiring

A Portrait of Etta and Claribel Cone

MARY GABRIEL

2002 by Mary Gabriel

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any

electronic means, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the publisher,

except by a reviewer, who may quote passages in a review.

All works and photographs reproduced herein are done so with

permission, gratefully acknowledged, of the Baltimore Museum of

Art, and are in the Cone Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art,

formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore.

Published by Bancroft Press

books that enlighten.

PO Box 65360, Baltimore, MD 21209

800.637.7377

www.bancroftpress.com

ISBN 1-890862-06-1

Library of Congress Card Number: 2002109262

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

Cover design, insert design, and author photo:

Steven Parke, What?design ()

Interior design: Theresa Williams ()

Preface

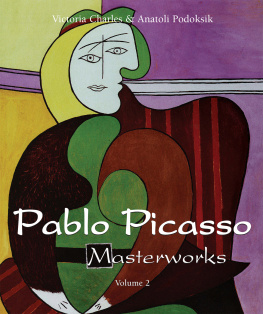

A s an undergraduate at the Maryland Institute College of Art, I first encountered the Cone collection in its natural habitatthe stark white walls of the Baltimore Museum of Art. Absorbed by the art in brilliant displaythe Matisses, Picassos, and magnificent Gauguin, Vahine no te Vi (Woman With Mango)I wouldn't have given even a moment's thought to the collectors, Etta and Claribel Cone, if the museum had not recreated, albeit behind glass, a small sliver of one of the rooms in one of the private Baltimore apartments where the Cone sisters had originally housed all their illustrious holdings.

This BMA recreation was no bigger than a large closet, but it glowed with warmth, and it beckoned with a sensuality precisely mirroring the Matisse paintings that I, the aspiring student of painting, had just been examining and dissecting. At that moment, I was struck by the fact that the Cone sisters not only bought paintings to live with, but had stepped through the canvases to live in the paintings they bought.

I was both amazed and curious. For me, the essential question was: why did two seemingly severe, upright women, both born around the time of the U.S. Civil War, both clinging to the cloak of Victorianism in their dress and attitude, surround themselves with such avant-garde and erotic art? Etta and Claribel Cone were paying tens of thousands of dollars for art pieces that were as scandalous in their day as Robert Mapplethorpe's or Damien Hirst's are in ours.

In my search for an answer, I found only more questions, so I began to read. The ample literature narrating the events of 1905 Paris, when Leo Stein discovered Picasso and Matisse, frequently mentions the two Cone sisters, I discovered. But Etta and Claribel Cone are most often referred to peripherally as Baltimore acquaintances of Leo Stein and his sister, Gertrude, who had decided to be a writer. Sometimes Etta and Claribel are described as the Steins distant relations. And just as often, they are dismissed as wealthy spinsters convinced by Gertrude Stein to spend some of their fortune on artists they neither understood nor appreciated. They are depicted as decidedly lesser lights in the luminous Paris of the early twentieth century.

In those rare instances where the two sisters gain even a modicum of credit for courageously collecting works by artists the world ridiculed, Dr. Claribel Cone is identified as the more important and visionary of the two sisters.

From this early research, I reached one preliminary conclusion that I believe still to be correct. Had they been men, annually purchasing works by Czanne, Matisse, and Picasso, the two sisters would have immediately been accorded the status and stature of accomplished art collectors. Because they were women, however, and women from Baltimore, no less, they were dismissed as indiscriminating shoppersand not just for art, but for many other collectibles as well.

History, I later concluded, was content to ignore or misrepresent the Cones. I came increasingly to blame their plight on Gertrude Stein. In her famous book, The Autobiography oj Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude dismissed the sisters of the world's greatest artists to survive and thriveand contemporary audiences to appreciate them first-hand. But for the collectors, art history might well have taken an entirely different shape and direction.

During their lifetimes, the Cone sisters allowed selected visitors to view their collection, and lent pieces to specific exhibitions, but the entire Cone Collection was not available for public view until after Etta's death in 1949, when it was bequeathed to the Baltimore Museum of Art. In January 1957, the BMA opened the Cone Wing, and the works went on permanent exhibition, finally allowing the public to see exactly what those two crazy sisters had been hiding in their Baltimore apartmentswhat exactly had kept them so busy for so many decades.

They roamed the galleries of Europe like addicts, for 45 years that spanned two world wars, and built and donated one of the most important art collections in the world. Yet the story of Etta and Claribel Cone has been the subject of only a handful of publications. In her latter years, Etta Cone herself worked furiously on, and spared no expense for, a catalogue setting forth all the elements of the collection. But when the catalogue became popular, she decided not to reprint it or to widen its distribution.

The Baltimore Museum of Art, which houses the collection, has published several Cone catalogues linked to exhibitions or anniversaries, the most recent being Jack Flam's Matisse in the Cone Collection: The Poetics of Vision (its 2001 publication coincided with the April 2001 opening of the renovated Cone Wing); and Brenda Richardson's Dr. Claribel & Miss Ettafirst published in 1985, and reprinted in 1992, it apparently went out of print in 2000.

In addition, Barbara Pollock, for Bobbs-Merrill, authored a biography of the sisters in 1962, The Collectors: Dr. Claribel and Miss Etta Cone, which is out-of-print as I write this prologue, and has been for some time.

Finally, various members of the Cone family have added their writings on the sisters over the years.

But in the general literature of 20th century art history, the full and accurate story of the two Cone sisters has been omitted. In this book, I have attempted to do what is long overdue: resurrect and bring to life two of the world's greatest art collectors, and to depict their undying passion for art that so many others initially despised, and that now is almost universally revered.

Mary Gabriel

Baltimore

July 5, 2002

Prologue

Baltimore, 1930

... My two Baltimore ladies... are sistersone of them... a great beauty, noble and glorious, lovely hair with ample waves in the old stylesatisfied and dominatingthe other with a majesty of a Queen of Israel... but with a depth of expression which is touchingalways submissive to her glorious sister but attentive to everything...

Henri Matisse to Simon Bussy, May 24, 1934

O n December 17, 1930, Etta Cone waited anxiously in her Baltimore apartment for Henri Matisse to arrive. Eight stories above a once grand street, now the site of scattered gambling dens and prostitutes, Etta and her sister Claribel had built a virtual shrine to the French master. Like his paintings, their rooms off the dark halls of the Marlborough Apartments were vibrant with exotic patterns and bursting with color: Eastern rugs on the floor, needlework pillows on overstuffed chairs, and Indian shawls and Italian textiles that luxuriously draped every available surface.