ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.

Copyright 1999 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved . No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the publisher.

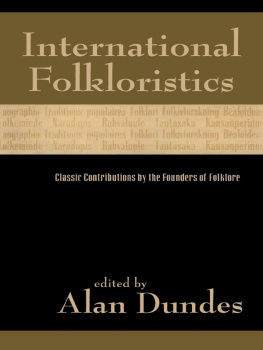

International folkloristics : classic contributions by the founders of folklore / edited by Alan Dundes.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Folklore. I. Dundes, Alan.

Preface

This book came into being for several reasons. First and foremost was to confirm the existence of international folkloristics as an independent, worldwide, world-class academic discipline. Second was to present a selective historical view of some of the theoretical highlights of the evolution of folkloristics, the study of folklore. And third was simply a pragmatic wish to facilitate the teaching of folkloristics. The letters and articles included in this volume are all writings I think serious students of folklore should read.

There has been much turbulent debate about the definition of folklore ever since the term was proposed in 1846. Some folklorists oppose its usage on nationalistic grounds, not wishing to employ an English word for their traditions. But even some English and American folklorists are not happy with the term and would like to do away with it and replace it with some other word. If one defines folkloristics as the study of folklore (as linguistics is the study of language), however, then it seems reasonable to retain folk-lore as the subject matter of folkloristics.

One way of defining folklore is to divide the word into its two constituent parts: folk and lore. A folk is any group of people whatsoever who share at least one common linking factor. It does not matter what that linking factor is; it could be nationality, ethnicity, religion, occupation, kinship, or any similar factor. Folk is a flexible concept, and a folk can be as large as a nation and as small as a village or a family. Moreover, individuals can obviously belong to more than one folk group. A single person may know family folklore, ethnic folklore, occupational folklore, religious folklore, and national folklore.

Lore refers to several hundred forms or genres, any one of which could occupy the attention of a folklorist for a lifetime. Folklore genres include epic, myth, folktale, legend, folksong, proverb, riddle, folk dance, superstition, games, gestures, foodways, folk costume, and many, many more. Genres may range from the very complexfor example, a festival or holiday celebrationto the relatively simple, such as tonguetwisters and curses. All folklore, no matter what genre, will exhibit multiple existence, meaning that an item will exist in more than one time and place; moreover, as a result of the transmission process from person to person, there will inevitably be variation. No two versions will be exactly the same. The presence of multiple existence and variation distinguishes folklore from so-called high culture and also from mass or popular culture. Great novels, symphonies, paintings do not change over time, and there is usually just one version of them. The same is true for motion pictures, television programs, comic books, and other types of popular culture. Moreover, the authorship of detective stories, science fiction, westerns, and romances is known, whereas the authorship of folklore is usually not known. Most folklore is transmitted orally or by example (e.g., gestures), but some folklore is writtenfor example, autograph book verse, epitaphs, latrinalia (bathroom wall writings), and photocopier or FAX folklore. These latter genres do manifest multiple existence and variation and therefore qualify as bona fide folklore.

Folklore as defined in the nineteenth century tended to be much more limited than the conception here. The folk were thought to be peasants, the illiterate in a literate society. Without literacy, the only forms of folklore were restricted to those that were orally transmitted. In Europe where the discipline of folkloristics began, the peasant was virtually the sole focus of folkloristics. The German term Volkskunde and the Scandinavian notion of folk life (rather than folklore) tended to refer to all aspects of peasant existence (or what anthropologists would call ethnography). Volkskunde or folk life was therefore essentially peasant ethnography. This meant that on the one hand the European concept of folk was rather narrow compared to the any group whatsoever definition, but at the same time the lore portion of the European concept was much broader than a specific set of genres inasmuch as it included everything a peasant did or thought.

It is necessary to know the older European concept of folk to understand the essays written by nineteenth- (and some twentieth-) century folklorists. Peasants were and are, of course, one type of folk, but the point is that they are not the only type of folk. There are many urban folk groupsfor example, labor unions, civil rights groups, and professional athleteswith each of these groups sharing its own specific folk speech, folk beliefs, and other traditions. The shift from defining folk as peasant to folk as a variety of diverse groups, both rural and urban, is an important part of the evolution of international folkloristics. The recognition that although oral tradition is undoubtedly the most common means of transmitting folklore it is no longer considered a sine qua non as a criterion for defining folklore represents another critical change in the nature of folkloristic research.

Anyone who teaches folklore knows very well that no two folklorists would necessarily agree on exactly what required readings should be assigned. There are, as in any field of inquiry, legitimate differences of opinion as to what the classics are. Moreover, most college and university courses in folklore tend to be restricted either by national boundaries or intentional limitation of genre. Hence a course in, say, mythology or American folklore would be unlikely to insist that students enrolled read the majority of the essays in this book. On the other hand, it is my personal conviction that anyone interested in any aspect of folklore in whatever national context or whatever genre ought to be familiar with the contents of this book. There is an important intellectual heritage in folkloristics, and it deserves to be better known.

Clearly, then, there is bias in the selection of folklorists contributions for this unusual anthology. Had it been conceived by some other folklorist, no doubt different essays might have been included and almost certainly some of those found in this volume would have been omitted. Not all of those whose writings were chosen qualify as full-fledged folklorists. Yeats was a poet, Freud was a psychoanalyst, Gramsci was a Marxist philosopher of political protest, but all of them nevertheless made significant contributions to folkloristics. To be sure, the majority of those selected were dedicated folklorists, including Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Mannhardt, Reinhold Khler, Giuseppe Pitr, Kaarle Krohn, Axel Olrik, Arnold van Gennep, Vladimir Propp, and Carl Wilhelm von Sydow. The essays are presented more or less in chronological order to give some sense of the evolution of international folkloristics. Despite the diverse national origins of the contributors, the careful reader will discover that the majority of the folklorists knew one another and were familiar with their international colleagues publications.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.