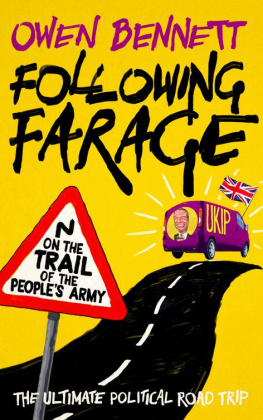

F OR THOSE OF YOU looking for a forensic analysis of the successes and failures of Nigel Farage and the United Kingdom Independence Party, I apologise. This book is not it.

But for those of you who want an idea of what it is like to report on, drink with, laugh at, and even, at times, defend the Peoples Army and its seemingly indestructible commander-in-chief, please read on.

In place of expertise, I offer you anecdotes. In place of objectivity, I offer you the opinions of a hack struggling to get to grips with a world he has always wanted to be a part of, but is slightly unsure of what to do when he gets there.

My journey on the trail of the Peoples Army saw me develop many friends both inside and outside the party. The ones inside shall remain nameless for obvious reasons, but those outside deserve my thanks.

Robert Hutton was far too generous with his time, Philip Cowley was far too generous with his ideas, and Christopher Hope was far too generous with his patience. John Stevens, Laura Pitel, Rowena Mason, Tamara Cohen, Mary Turner and Michael Deacon deserve special mention for their roles as supporting artists in this tale, as do Matthew Holehouse, Alex Wickham, Giles Dilnot, Dan Hodges and Isabel Hardman.

My colleagues at the Express, Alison Little, Martyn Brown, Macer Hall and Jackie Murray, all deserve special thanks for their advice and tolerance. The same goes to Jason Beattie, Kevin Maguire, Jack Blanchard and Ben Glaze at the Daily Mirror.

Special thanks, and an apology, go to Alessandra Pino, who heard more about Nigel Farage over the course of writing this book than can be healthy.

And, of course, thanks to my family, who know what theyll be getting for Christmas this year.

We were written off as a party, we were cranks, gadflies, fruit flies, extremists, and the Prime Minister even called us closet racists, so weve had to put up with a bit of stick over the years to get to where we are.

Nigel Farage, 3 April 2013, in Lydney,

Gloucestershire, during his Common Sense tour

11 APRIL 2013

D EXYS FUCKING MIDNIGHT RUNNERS , he spat out with venom. The groups biggest hit Come On Eileen was blaring out of the pubs speakers.

Not a fan? I asked. (Us journalists can pick up on subtle hints like these.)

Nigel Farage sniffed before replying: Honestly, I would ban music in pubs.

He took another gulp of his ale.

I didnt really know what to say to that. Ive got nothing against Dexys. Granted, Geno is a far superior tune to Come On Eileen, but I dont think it was Kevin Rowlands musical shift from a Northern Soul-influenced New Wave act to chart-topping pop star that had annoyed Farage.

Despite the anti-Dexys or, rather, music in general proclamation, Farage looked relaxed. Of course he was. He was in his comfort zone drinking warm ale in a pub after spending an hour working up a thirst by canvassing. He was relaxed now, but the day hadnt started off smoothly.

The UKIP bus had broken down, making him late. An hour and a half before our lunchtime pint, I had been with a small crowd of UKIP supporters gathered by the clock tower in the town centre waiting for Farages arrival. There were no more than thirty of them, but they stood out. To be honest, any group of people gathered together in Hoddesdon town centre on a damp, grey morning in April is going to stand out. The Hertfordshire town is not known for its hustle and bustle. The purple balloons attached to a table, complete with a giant UKIP banner tied between two bollards, added to the spectacle.

But still, it was only thirty people. I certainly didnt look at them and think they were a Peoples Army. But this was April 2013, before all the Peoples Army rhetoric. Before the UKIP fox was in the Westminster hen house. Before defections.

Farage was well known, but still seen by many especially in the media as an eccentric. Some felt he was dangerous; some felt he was comical; most felt he was irrelevant.

UKIP had a handful of MEPs, but they kept defecting, getting sacked or saying ridiculous things such as all Muslims should sign a declaration promising they werent going to become terrorists.

The party seemed destined to be on the political fringes. Even after successes in the European elections in 2009 and 2004, UKIP had failed to win any seats in the Commons in the following years general elections. It only had seven local councillors across England, and support for the party was erratic its polling fluctuated between 10 and 17 per cent in the first eleven days of that April alone.

Farage was coming to Hoddesdon as part of that years local election campaign, and it was to be my first of many encounters with him.

Margaret Thatcher had died earlier that week, and suddenly everyone was a Eurosceptic Tory again. Good old Maggie, she wouldnt have taken any of this nonsense from the EU. She would have controlled immigration. She would have defended our high-powered vacuums. She wouldnt have voted to keep us in a single-market union in 1975. Well, maybe not the last one.

I was working for the Hertfordshire Mercury and, although Hoddesdon wasnt my patch I had recently been given the much quieter beat of Buntingford I had been sent down to report on Farages visit.

I had already begun shifting on the Daily Express website at weekends, and, in a few weeks, would be leaving the world of local news and joining the Express permanently hence the Mercury editors decision to relegate me to the trainee beat of Buntingford to serve out the last few weeks of my notice.

Farage was running late and so, notebook in hand, with a pen slotted into the wire rings at the top, I paced around.

I had already done my vox pops, picking out a number of supporters to get comments from the youngest, the eldest, anyone who looked vaguely interesting.

No one had said anything too remarkable too much immigration, sick of Europe, down with this sort of thing and I knew, even as I spoke to them, their comments probably wouldnt get in the piece. Vikki, the papers photographer, was taking some pointless snaps. She knew they were pointless but, like me, wanted to look busy. It was all very different from what the local UKIP organiser had promised in his press release: UKIP leader Nigel Farage will parade through Hoddesdon in a branded bus as part of his tour of the county ahead of the local elections next month.

I was expecting an American-style, open-top election bus, complete with a loud hailer bellowing out into the streets of Hoddesdon that everyone must Vote UKIP in the upcoming election.

I was expecting a carnival atmosphere; a swarm of people descending on the town centre, all hoping for a glimpse of their Dear Leader all hoping for a wave from the man with a cigarette in his mouth, a pint in his hand and St George in his heart.

I was expecting too much, clearly.

As it was, with the grey April sky overhead threatening rain, I, like the others, was waiting to see if Farage would arrive at all.

UKIPs local organiser, a market-stall holder called David Platt, chatted with members of the crowd before he bounded up to me. He cheerily told me the UKIP bus had broken down near Norwich, and Farage and other party members were on alternative transport.

![Atkinson - An army at dawn: [the war in North Africa, 1942-1943]](/uploads/posts/book/178818/thumbs/atkinson-an-army-at-dawn-the-war-in-north.jpg)