Introduction

I had rather be shut up in a very modest cottage with my books, my family and a few old friends, dining on simple bacon, and letting the world roll on as it liked, than to occupy the most splendid post, which any human power can give. Thomas Jefferson

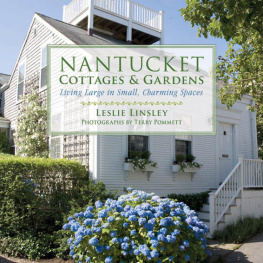

Beach house, farmhouse, saltbox or cabinwhat makes a cottage? This is the question we were often asked in the year we spent photographing a variety of cottages for this book.

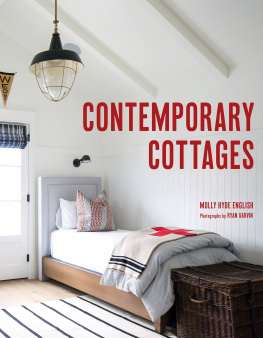

We found that what defines a cottage is much more than just an architectural type or style of dwelling. A good cottage is a home with a sensibility of mind and place that suggests comfort and simplicity, where modesty of scale and avoidance of pretense afford the freedom to live according to personal desires and tastes.

As Jefferson believed, a cottage is a place where richness is to be found in the luxuries of time and privacy, a place in which to garden, read, cook and enjoy lifes pleasures. Out of a fairly modest place, extraordinary things can come.

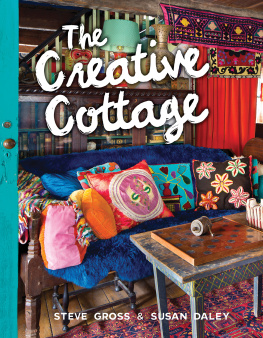

The cottages we discovered for this book are the homes of artists, preservationists and visionaries, people with creative abilities and imagination. They are not furnished according to any one period or style, but have evolved over years as a collage of things from different eras, containing old and new elements that come together to create a pleasing whole.

Although the homeowners show a proclivity for timeworn things that come from the past, they also exhibit a modern translation of decor and current tastes. From minimally furnished to ornately decorated ones, the houses have the strong tactile qualities of rough wood and beams, patched floors, creaky stairs and much patina.

Inside, the furnishings draw on memories, history and reminiscences and act as repositories of favorite things. There is a plenitude of art objects, books, heirlooms, vintage collections, painted murals, hand-made wallpapers and homemade furniture, as well as the wood-burning stoves and fireplaces, the geraniums on the windowsills, and the cozy nooks and cupboards usually associated with cottage life.

The houses shown are, in general, all fairly old ones, with the inhabitants liking things to look their age and having the understanding that an old house must be allowed to look like one, although anachronisms and modern conveniences are allowed. Some of the buildings did not actually even start out as cottages; there is a beach house that used to be a ship captains warehouse, and a country house that used to be a blacksmiths forge. But they were cleverly transformed into cottages by people who knew how to gently alter them and furnish them in a cottage-like spirit.

The homeowners have added on to their buildings with new rooms, walls, floors, ceilings and windows, as well as having subtracted the same, sometimes stripping away to leave only the bare essentials. They have discerned how to ingeniously make the most of small spaces, according to their desires and needs. It is a constantly changing process of renovation and revival.

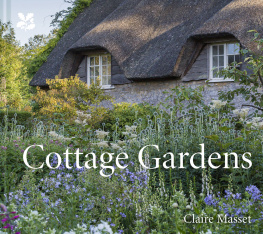

As cottages are generally rural, the houses also share a deep connection with the outdoors, and are on intimate terms with their natural environments, fitting well into their surrounding landscapes. Some have half-wild gardens or box-lined patios, some have screened porches for sitting and dining, and some have French doors that open out to blend indoors with outdoors easily. One of the chief luxuries of living in these places is being in close contact with nature and enjoying the views and the changing of seasons.

There will always be a longing for some people to escape to a small cottage situated in a forgotten village, perched on top of a forested mountain, hidden down a dirt road or clinging to the rocks beside the sea, like the ones shown in this book. We hope that these examples will inspire you to see the intrinsic beauty and possibilities of simple dwellings and to create your own outstanding version of the cottage.

Cape Cod Revival

Landscape painter John Dowd inhabits a 1750 cottage in Provincetown, an old seacoast town on the tip of Cape Cod. The town, which has been a whaling port, a Portuguese fishing village, a beach resort and a major art colony, has long attracted an array of artists, writers, eccentrics and visionaries, who brought with them an imaginative lifestyle.

Drawn there by the ocean light and the picturesque surroundings, artists found they could stay in inexpensive boarding houses and rent studios very cheaply. In the same way, Dowd came to Provincetown the summer after he graduated from Notre Dames School of Architecture, and worked at a guesthouse in exchange for free rent.

He began painting buildings in landscapes instead of designing houses and eventually found himself buying an old cottage that had been on the market for years. The house was unwanted, unloved, and covered in ugly aluminum siding, which, to his relief, all peeled off in one afternoon, like foil on a baked potato.

Though the house was not attractive in any way, it was big enough to have an art studio, and John felt there was character lurking behind some unsightly renovations. His idea was not to undertake a total makeover. Instead, he set out to put the house back the way it used to be, on a budget of just about zero, using building materials he mainly found or salvaged.

Having in his mind a memory of his grandparents antique-filled Victorian to emulate, and with an artists eye for detail, he haunted salvage yards and junk shops. Things began to come to him serendipitously, finding their way to the house and settling in, looking like theyd been there for a hundred years or more.

Fortuitously, John happened to find an elegant mantel and china cabinet from a similar Cape Cod cottage that fit perfectly into his own living room, which was missing those elements. For the kitchen, he came upon an old woodstove and a Victorian table like the ones he remembered from his childhood.

Reclaiming used things that had been rejected by others, John realized that what he liked best about them were the imperfections, which is what makes them more interesting. His house today serves not only as a repository of his personal memories but also as a small archive of Provincetown art history. Hanging on his walls