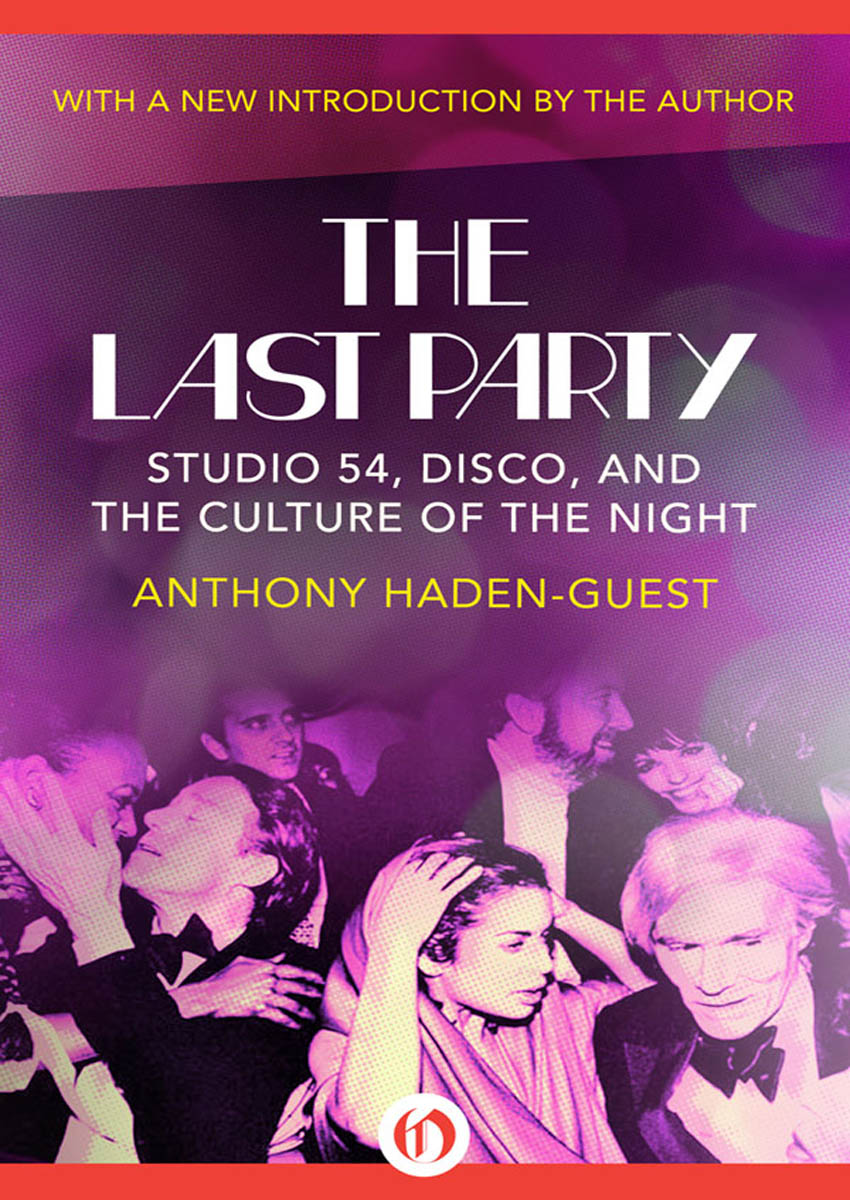

The Last Party

Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night

Anthony Haden-Guest

Now the night comes

and it is wise to obey the night

Homer, The Iliad, VII

TAKE YOUR PARTNERS

MAURICE BRAHMS GOT INVOLVED WITH MANHATTANS Nightworld entirely on account of John Addison, who arrived from South Africa in the early seventies. He was a second cousin of mine. He stayed with me in Brooklyn, Maurice Brahms says. The cousins were unalike. Brahms was of middling height, garrulous, straight, and dressed like a businessman, whereas Addison was tall, gay, secretive, and elegant. Brahms had a front-stage demeanor, like an actor doing monologue. Addison liked to lurk in the wings. But the cousins got on fine. Both were ambitious, tough, and sharp, and both could grip a dollar hard enough to make it squeal with pain.

Maurice Brahms had been in the restaurant business since he was seventeen. My father bought a restaurant for my uncle, but he died after a couple of years. I took it over, Brahms says. The place was the Colonel at 101 Park Avenue. John Addison had an uncle who owned a parakeet business in Ventura County in Southern California, and he himself had studied horticulture in South Africa, but horticulture not being huge in Manhattan, he signed up with Ford as a model. He did well from day one says Jerry Ford. He worked with Francesco Scavullo and became a long-term lover of the photographer. Addison also took a backup job as a waiter in Yellowfingers, a restaurant in midtown on Third Avenue. Unlike most MAWs (Model Actor Waiters) Addison quickly decided he liked the restaurant business. Preferred it, in fact, to the glam drudgery of modeling.

Juice bars were big in those days. Addison opened one up not far from the Ford Model agency, under the 59th Street Bridge. He called it Together. He was a night person and I was a day person. I never had a nightlife, says Brahms. He opened up my eyes. When I saw how many people were going out at twelve oclock at night. And paying five dollars for a Coca-Cola and five dollars for admission! And I had a restaurant and I would get thirty-five cents for a Coke and they would scream and yell it was too much money. I said what the hell am I doing? I should be doing what hes doing. Thats part of the magic of the night, the way that the moon and stars, though invisible, smothered in the contaminated skies of big cities, nonetheless manage to charm silver and gold out of pockets that are zippered shut in the daylight.

Fancy clubs at the time, like El Morocco and Le Club, were straitlaced, if not completely straight, so Le Jardin, which was on two separate floors in the Diplomat Hotel on West Forty-third Street, the penthouse and the basement, was a breakthrough. Though fashionable straights were made welcome, Le Jardin was essentially gay. And there were some very pretty women there, notes Bill Oakes of RSO. Which was obviously one reason gay discos broke out. Women could go and dance there without guys hitting on them. Also welcome were every sort of exotica. Patti Smith sang at Le Jardin, for instance, soon after making it at CBGB as chanteuse. Le Jardin was stylish, with bowls of fruit and cheese on tables. It was a bellwether of what was to come.

Brahms and Addison started to make the rounds of Nightworld. The place that Brahms found riviting was a gay club, Flamingo. Flamingo had been started in 1975 by Michael Fesco, a former Broadway dancer, a gypsy in the chorus of Irma La Douce. It mostly had gay male members, who each paid six hundred dollars a year. Flamingo was in an upstairs loft space, and there were two stunning women on the door, with gardenias behind their ears and Tuinal smiles. Since there was some fear of drug busts the club had an unlisted telephone number, but initiates knew they would find it under Gallery for the Promotion of People, Places, and Events at 599 Broadway.

Michael Fesco, a club owner and promoter, says that running a gay club at the time was a breeze. For the seven years that I was at Broadway and Houston, we never had any problem with the neighbors, he says. Everybody was gay, queer. Who cared? Now it seems like everyone cares. AIDS came along and the whole gay issue became a kind of a phenomenon. And we got into a lot of trouble with the religious right and rednecks around the country.

The only women regulars at Flamingo, the Tuinal smiles aside, were a couple of disco music nuts. I would haul along the latest records in a milk crate or a canvas tote bag, says one of them, Robin Sciortino. The club was famous for the intensity of its ambience and for its theatrically inventive parties. There were Black parties and White parties, says a habitu, writer Stuart Lee. He remembers a live pig scarfing down copies of Vogue and Harpers Bazaar that people would toss into its pen, and set pieces such as a Crucifixion with the models dressed as Roman legionaries, and a Jesus Christ who would, from time to time, turn his eyes heavenward and ascend a cross.

Maurice Brahms, a straight middle-aged businessman, wasnt offended by the Flamingos inventive cabaret at all. I saw a tremendous potential for the gay market that wasnt being utilized. All the clubs that they had were raunchy and secondary, he told me. Even Flamingo itself didnt scratch the surface. If people will pay this much for soda with a jukebox, my God, what if somebody built a real club for the gay population? It could explode.

Brahms began to nose around looking for a venue. He finally lighted upon a former envelope factory at 653 Broadway. You had those Hare Krishna people there. And the landlord was getting only two hundred dollars a month, Brahms says. The landlord asked me for a thousand dollars a month. I told him, Ill give you twelve or thirteen hundred, but I want a lease of fifteen years. Where I can do whatever I want. He gave me everything I wanted. He thought I was crazy.

I spent like a hundred and fifty thousand dollars opening that club. That was unheard of, to put that kind of money in. It was painted black inside, with neon balls. And it had no name outside. I felt the whole mystique of the place was to make a person struggle to find it. There were mirrors on the sides. If you looked in the mirror, the neon balls just went on forever. Which gave the club its name: Infinity. Brahms says, We advertised in Michaels Thing, a gay magazine, and we did a membership, and I said, COMING SOON! COMING SOON! with a penis sign and then ITS FINALLY COME!

And as part of the decor there was a six-foot penis of pink neon at Infinitys opening in the fall of 1975. I made two openings, one for eight oclock and one for ten oclock, Brahms says. He had invited his straight, or at least uptown list, for eight, assuming they would clear the place to make room for the downtown gay crowd. But at ten-thirty the room was still so crowded, he says. Nobody left. There were probably two thousand people in the street. That was the market I had really targeted, and they couldnt get in.

We didnt have anyone at the door with a guest list, Brahms says. It didnt exist. Its wonderful when theres no other place to go. I was the only place to go. Nobody knew how to spell discothque. Brahmss fingers fluttered through clippings. Donna Summer and the Pointer Sisters. They were just there, partying. Nobody paid them. They paid admission when they came in.

My policy was: Everybody pays! I wasnt there to become famous. I was there to make as much money as I possibly could. His fingers flew through his press clips and he found a 1975 headline in