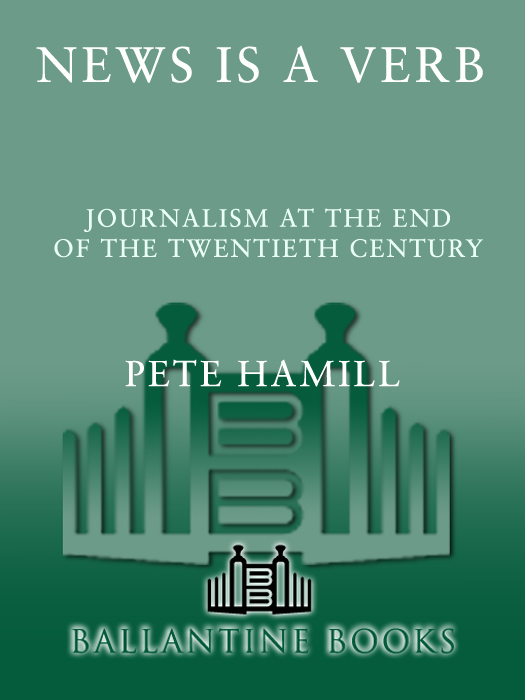

T HE LIBRARY OF

C ONTEMPORARY T HOUGHT

Americas most original voices

tackle todays most provocative issues

PETE HAMILL

N EWS IS A V ERB

Journalism at the End of the

Twentieth Century

With the usual honorable exceptions, newspapers are getting dumber. They are increasingly filled with sensation, rumor, press-agent flackery, and bloated trivialities at the expense of significant facts. The Lewinsky affair was just a magnified version of what has been going on for some time. Newspapers emphasize drama and conflict at the expense of analysis. They cover celebrities as if reporters were a bunch of waifs with their noses pressed enviously to the windows of the rich and famous. They are parochial, square, enslaved to the conventional pieties. The worst are becoming brainless printed junk food. All across the country, in large cities and small, even the better newspapers are predictable and boring. A movie director once said of a certain screenwriter: He aspired to mediocrity, and he succeeded. Many newspapers are succeeding in the same way.

The Library of Contemporary Thought

Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group

Copyright 1998 by Deidre Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by The Ballantine Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

http://www.randomhouse.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hamill, Pete, 1935

News is a verb / Pete Hamill.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76676-2

1. JournalismUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

PN4867.H36 1998

071.30904dc21 98-5896

v3.1

This book is in memory of the following men and women, journalists all, who were killed doing their jobs in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos

- Arpin, Claude

- Bailly, Francis

- Bellendorf, Dieter

- Birch, Michael

- Bun Ly, Thun

- Burrows, Larry

- Cantwell, John

- Capa, Robert

- Caron, Gilles

- Castan, Sam

- Chan, Nun

- Chapelle, Dickey

- Chellappah, Charles

- Colne, Roger

- Dara, Chan

- Eggleston, Charles R.

- Ellison, Robert J.

- Ezcurra, Ignacio

- Fall, Bernard

- Faye, Sam Kai

- Flynn, Sean

- Frosch, J. Frank

- Gallagher, Ronald D.

- Hangen, Welles

- Herbert, Gerard

- Hirons, Alan

- Huet, Henri

- Hung Cuong, Duong

- Ichinose, Taizo

- Ishii, Tomoharu

- Ishiyama, Koki

- Khoo, Terry

- Kolenberg, Bernard

- Kusaka, Akira

- Laramy, Ronald B.

- Laurent, Michel

- Leandri, Paul

- Lekhi, Ramnik

- Miller, Gerald

- Mine, Hiromishi

- Mongkol, Tou Chhom

- My, Huynh Thanh

- NoonanJr., Oliver E.

- Pigott, Bruce S.

- Potter, Kent

- Reese, Everette

- Reynolds, Terry L.

- Rose, Jerry

- Sakai, Kojiro

- Sakai, Tatsuo

- Savanuck, Paul D.

- Sawada, Kyoichi

- Schuyler, Philippa Duke

- Shimamoto, Keisaburo

- Shimkin, Alexander

- Stone, Dana

- Sully, Francois

- Syvertsen, George

- Takagi, Yujiro

- Takano, Isao

- Van Thiel, Pieter R.

- Vichith, Sou

- Wakabayashi, Hiroo

- Waku, Yoshihiko

- Yanagisawa, Takeshi

- Source: The Freedom Forum Journalists Memorial, Washington D.C.

CONTENTS

Introduction

T HIS IS NOT an objective or neutral essay. The subject is so deeply entwined with my life that I cant write about it in a cold, detached manner. Quite simply, I love newspapers and the men and women who make them. Newspapers have given me a full, rich life. They have provided me with a ringside seat at some of the most extraordinary events in my time on the planet. They have been my university. They have helped feed, house, and educate my children. I want them to go on and on and on.

The newspaper that gave me my life was the New York Post, as published by a remarkable, idiosyncratic woman named Dorothy Schiff and edited by a tough, smart, old-style newspaperman named Paul Sann. I started there on June 1, 1960, working the night side as a reporter. The Post was then, and is now, a tabloid. That blunt little noun has a pejorative quality these days, but tabloid really is a neutral word, describing the shape of the page. Tabloid cant, with any accuracy, describe the style, content, or intentions of Newsday, the National Enquirer, the Rocky Mountain News, the New York Daily News, the Boston Herald, the Star, the New York Post, the Philadelphia Daily News, or the Globe. All are published in tabloid format. But the Star, the National Enquirer, and the Globe are supermarket weeklies, whose basic goal is to entertain their readers, usually with tales of celebs-in-trouble. The rest are dailies, engaged in the traditional effort to inform their readers about their city, their nation, and the world. All tabloids are different, shaped by separate traditions and geographies. The daily newspapers that have enduredtabloid or broadsheetare those that best serve the communities in which they are published. But the supermarket weeklies dont serve communities; they are national publications driven by an almost primitive populism. Like the mass-circulation Fleet Street tabloids that are their models, they are really about class. Their unsubtle message is as primitive as an ax: Dont feel so bad about your life, lady, these rich and famous people are even more miserable than you are.

So there are tabloids, and there are tabloids. Im proud to have spent most of my working life as a tabloid man at the Post, the New York Daily News, and New York Newsday. At the Post, I served my apprenticeshipcovering fires and murders, prizefights and riotsand did so in the best of company. Reporters in those days were not as well educated as they are now. Some were degenerate gamblers. Some had left wives and children in distant towns, or told husbands they were going for a bottle of milk and ended up back on night rewrite on a different coast. Some of them were itinerant boomers who worked brilliantly for six months and then got drunk, threw a typewriter out a window, and moved on. Some were tough veterans of the depression and World War II and were sour on the whole damned human race. But all of them were serious about the craft. And oh, Lordwere they fun.

It was their pride that they could turn out a fine, tough, tight newspaper with a fifth of the staff of the New York Times, and do it with great style. Let the Times be the New York Philharmonic; they were happy to play in the Basie band. They understood, and accepted, the limitations placed upon them by the tabloid format. Because space was very tight, every word must count. The headlines must sparkle. The photographs must add to the story, not simply illustrate it. And every story must have a dramatic point. There was no room for detailed analysis of the collapse of manufacturing in New York; you had to find a factory that was closing and a proud man or woman who might never work again. You couldnt just report a fire; you had to tell us about the people whose baby pictures and wedding albums had gone up, literally, in smoke. You had to look for good guys and bad guys, whenever they existed, and then save them from being cartoons with skepticism and doubt. Sometimes they slopped over into sentimentality or its twin brother, sensationalism, by expressing emotions they didnt feel. Most of the time, they were content to adopt a hard-boiled cynical manner, accompanied by a wink.