Dedication

This book is dedicated to Arfon Williams (Wil 71), formerly of the Royal Regiment of Wales, who has been a good friend to my father.

Author

Neil Grant studied archaeology at Reading University, and now works for English Heritage. His interests include firearms, medieval edged weapons and classical and medieval horsemanship.

Illustrators

Peter Dennis was born in 1950. Inspired by contemporary magazines such as Look and Learn he studied illustration at Liverpool Art College. Peter has since contributed to hundreds of books, predominantly on historical subjects, including many Osprey titles. A keen wargamer and modelmaker, he is based in Nottinghamshire, UK. Peter completed the battlescene illustrations in this book.

Born in Malaya in 1949, Alan Gilliland spent 18 years as the graphics editor of The Daily Telegraph, winning 19 awards in that time. He now writes, illustrates and publishes fiction (www.ravensquill.com), as well as illustrating for a variety of publishers (www.alangilliland.com). Alan completed the cutaway illustration for this book.

Acknowledgements

The author and editor would like to thank the staff and trustees of the Small Arms School Corps weapons collection for their invaluable assistance in the preparation of this book.

Editors note

Metric measurements are used in this book. For ease of comparison please refer to the following conversion table:

1km = 0.62 miles

1m = 1.09yd / 3.28ft / 39.37in

1cm = 0.39in

1mm = 0.04in

1kg = 2.20lb

1g = 0.04oz / 15.43 grains

Imperial War Museums Collections

Many of the photos in this book come from the huge collections of IWM (Imperial War Museums) which cover all aspects of conflict involving Britain and the Commonwealth since the start of the twentieth century. These rich resources are available online to search, browse and buy at

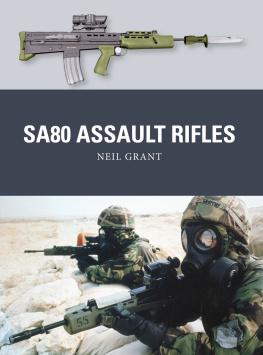

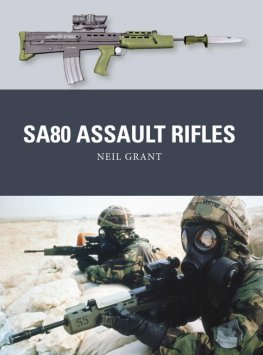

Front cover, above: An L85A1 Individual Weapon with an L3A1 Bayonet fitted. (Authors Collection)

Front cover, below: British troops armed with L85A1 Individual Weapons, wearing respirators and protective NBC suits during chemical warfare training just prior to the 1991 Gulf War.

( IWM GLF 400)

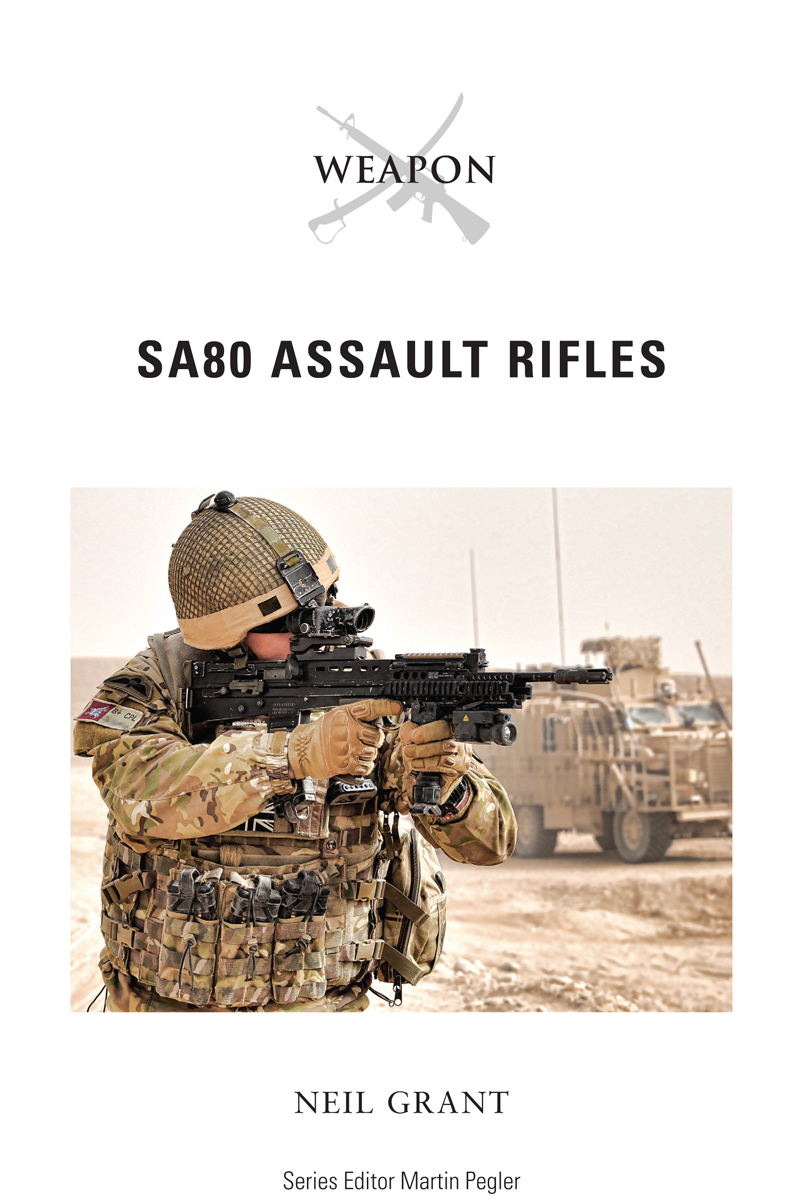

Title page: A soldier from 23 Engineer Regiment keeps watch with an L85A2 in Afghanistan in 2011. The Magpul polymer magazines are stored upside down in his webbing, with loops fitted to the bases for quick extraction. (MOD Crown copyright 2011)

Artists note

Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the artwork plates in this book were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All enquiries should be addressed to:

Peter Dennis, Fieldhead, The Park, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire NG18 2AT, UK, or email

The publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon this matter.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The SA80 is among the most controversial small arms adopted by a major power since World War II. Strictly speaking, the term SA80 refers to the whole Small Arms for the 1980s programme, including the L85 Individual Weapon (IW, as the British Army termed the rifle version), L86 Light Support Weapon (LSW), L22 Carbine and L98 Cadet Rifle. In practice, however, the term usually refers to the rifle version.

On paper, the concept looked excellent. The IW would replace both the 919mm Sterling submachine gun (SMG) and the 7.6251mm Self Loading Rifle (SLR), while the LSW would replace those examples of the L4A4 Light Machine Gun (essentially re-barrelled World War II-era Bren guns) still remaining in service and most examples of the L7 General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG), leaving only a few of the latter in use in specialized roles. The two new weapons would have a high degree of commonality, dramatically reducing the number of spare parts required in the supply chain. Their adoption would also simplify infantry training, since anyone familiar with one of the weapons would automatically be able to use the other. Meanwhile, advanced design features would result in the new weapons being more compact than anything else available an obvious advantage given the British Armys preoccupation at that time with mechanized warfare against Warsaw Pact forces in Central Europe and with urban patrolling in Northern Ireland. Even better, the new weapons and their ammunition would be significantly lighter than the designs they would replace, enabling soldiers to carry more ammunition despite the extra weight of the body armour coming into service at the same time as the new weapons.

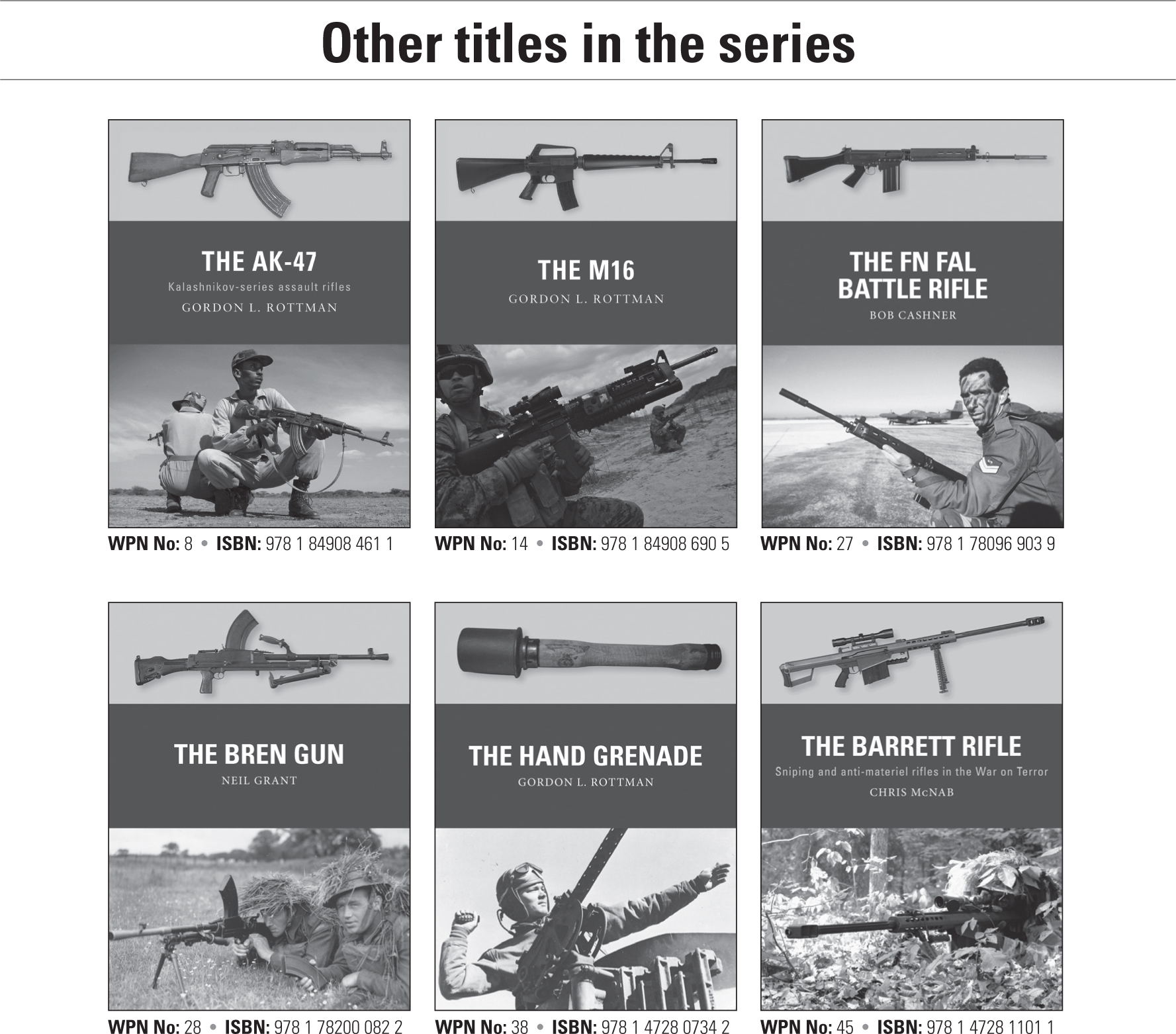

The main weapons of the SA80 system the L85A2 Individual Weapon (below) and L86A1 Light Support Weapon (above). The cocking handle changed from the original round type on the A1 weapon to a curved one on the updated A2 weapon. (Authors Collection)

The reality proved less rosy. The British Army actually found itself fighting very different wars from those it had anticipated, and weapons designed for mechanized combat in Europe proved less suitable for dusty desert environments. Some felt that the older and more powerful 7.62mm rounds would have penetrated the thick mud-brick walls of Afghan compounds better than their lighter 5.56mm replacements. The compromises required to keep the LSW compatible with the rifle version proved incompatible with the qualities needed from a good machine gun, and combat experience led to the GPMG making a comeback. Worse, corner-cutting in design and manufacture led to problems of poor reliability; and the reluctance of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to admit that the problems existed, and their tardiness in rectifying them, saddled the weapon with a poor reputation that damaged troop confidence and hindered any significant foreign sales. The problems with the SA80 became so notorious that they became a long-running scandal for the press to exploit. Serious consideration was even given to simply scrapping the weapon and buying a foreign design, rather than rectifying the problems.

Whatever ones opinion of the SA80 family, it has undoubtedly been a significant weapon, albeit not always in a positive sense. It has armed almost every British soldier for the last three decades, and will continue to do so for at least another decade, making it a notably long-serving weapon. It has been involved in the heaviest and most sustained fighting British troops have experienced since the Korean War in the early 1950s, including the First and Second Gulf Wars, the Iraqi insurgency that followed, and the long campaign in Afghanistan. It has led to the most significant changes in British small-unit organization since World War II, with consequent effects on tactics and doctrine. Finally, although its replacement has not yet been selected, the SA80 will almost certainly be the last wholly British-designed and -built rifle issued to the British Army.