Thank you for purchasing this Scribner eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

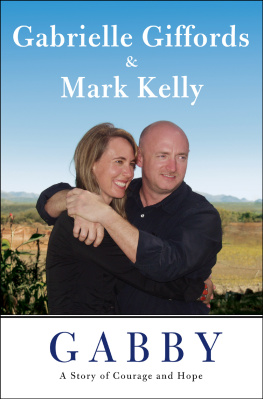

Copyright 2011 by Gabrielle Giffords and Mark E. Kelly

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition November 2011

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4516-6106-4 (print)

ISBN 978-1-4516-6109-5 (eBook)

In memory of

Christina-Taylor Green, Dorothy Morris,

John Roll, Phyllis Schneck, Dorwan Stoddard,

and Gabriel Zimmerman

CONTENTS

GABBY

CHAPTER ONE

The Beach

I used to be able to tell just what my wife, Gabby, was thinking.

I could sense it in her body languagethe way she leaned forward when she was intrigued by someone and wanted to soak up every word being said; the way she nodded politely when listening to some know-it-all who had the floor; the way shed look at me, eyes sparkling, with that full-on smile of hers, when she wanted me to know she loved me. She was a woman who lived in the momentevery moment.

Gabby was a talker, too. She was so animated, using her hands as punctuation marks, and shed speak with passion, clarity, and good humor, which made her someone you wanted to listen to. Usually, I didnt have to ask or wonder what she was thinking. Shed articulate every detail. Words mattered to her, whether she was speaking about immigration on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, or whether she was alone with me, talking about her yearning to have a child.

Gabby doesnt have all those words at her command anymore, at least not yet. A brain injury like hers is a kind of hurricane, blowing away some words and phrases, and leaving others almost within reach, but buried deep, under debris or in a different place. Its awful, Gabby will say, and I have to agree with her.

But heres the thing: While Gabby struggles for words, coping with a constant frustration that the rest of us cant fathom, I still know what shes thinking much of the time. Yes, her words come haltingly or imperfectly or not at all, but I can still read her body language. I still know the nuances of that special smile of hers. Shes still contagiously animated and usually upbeat, using her one good hand for emphasis.

And she still knows what Im thinking, too.

Theres a moment that Gabby and I are going to hold on to, a moment that speaks to our new life together and the way we remain connected. It was in late April 2011, not quite four months after Gabby was shot in the head by a would-be assassin. As an astronaut, I had just spent five days in quarantine, awaiting the last launch of space shuttle Endeavour, which Id be commanding. It was around noon on the day before the scheduled liftoff, and my five crew members and I had been given permission to see our spouses for a couple of hours, one last time.

Wed be meeting with our wives on the back deck of this old, run-down two-story Florida beach house that NASA has maintained for decades. It is on the grounds of the Kennedy Space Center, and theres even a sign at the dirt road leading to it that simply says The Beach House. The house used to have a bed that astronauts and their significant others would use for unofficial romantic reunions. Now its just a meeting place for NASA managers, and by tradition, a gathering spot where spouses say their farewells to departing astronauts, hoping theyll see them again. Twice in the space shuttles thirty-year history, crews did not make it home from their missions. And so after a meal and some socializing as a group, couples usually break away and take private walks down the desolate beach, hand in hand.

The 2,000-square-foot house is the only structure on the oceanfront for more than twenty-five miles, since NASA controls a huge chunk of Floridas space coast. Look in any direction and theres nothing but sand, seagulls, an occasional sea turtle, and the Atlantic Ocean. Its Florida pretty much the way it was centuries ago.

On our previous visit to this spot, the day before my shuttle mission in May 2008, Gabby and I were newlyweds, sitting in the sand, chatting about the mission, her upcoming election, and our future together. Gabby reminded me of how very blessed we both were; she often said that. She felt we needed to be very thankful for everything that we had. And we were.

The biggest problem on our minds was finding time to see each other, given our demanding careers in separate cities. It seemed complicated then, the jigsaw puzzle that was our lives, but in retrospect, it was so simple and easy. We couldnt have imagined that wed return for a launch three years later and everything would be so different.

This time, Gabby entered the beach house being pushed in a wheelchair, wearing a helmet to protect the side of her head where part of her skull was missing. It had been removed during the surgery that saved her life after she was shot.

While the others at the house had come in pairs (each astronaut with a spouse), Gabby and I showed up with this whole crazy entourageher mother, her chief of staff, a nurse, three U.S. Capitol Police officers, three Kennedy Space Center security officers, and a NASA colleague assigned to look after Gabby for the duration of my mission. The support Gabby now needed was considerable, and certainly not what my fellow crew members expected in their final moments with their wives. Instead of an intimate goodbye on a secluded beach, this became quite the circus. It was a bit embarrassing, but the men on my crew and their spouses were 100 percent supportive.

They understood. Gabby had just logged sixteen arduous and painful weeks sequestered in a Tucson hospital and then a Houston rehab center. She had worked incredibly hard, struggling to retrain her brain and fight off depression over her circumstances. For her doctors and security detail to give their blessings and allow her to travel, this was how her coming-out needed to be handled.

My crewmates and their wives greeted Gabby warmly, and she smiled at all of them, and said hello, though it was clear she was unable to make real small-talk. Some words and most sentences were still beyond her. Everyone was positive, but everyone noticed.

As I watched Gabby try to navigate the social niceties, I was very proud of her. She had learned since her injury that it could sap her energy and her spirits to be self-conscious about her deficiencies or her appearance. So she had found ways to communicate by employing upbeat hand motions and that terrific smile of hersthe same smile that had helped her connect with constituents, woo political opponents, and get my attention. She didnt need to rattle off sentences to charm a bunch of astronauts and their wives. She just had to tap into the person shes always been.

Next page