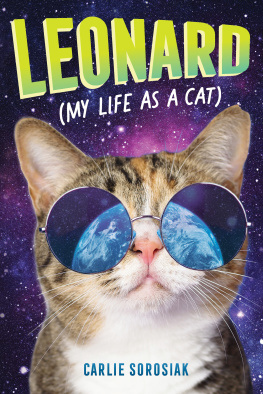

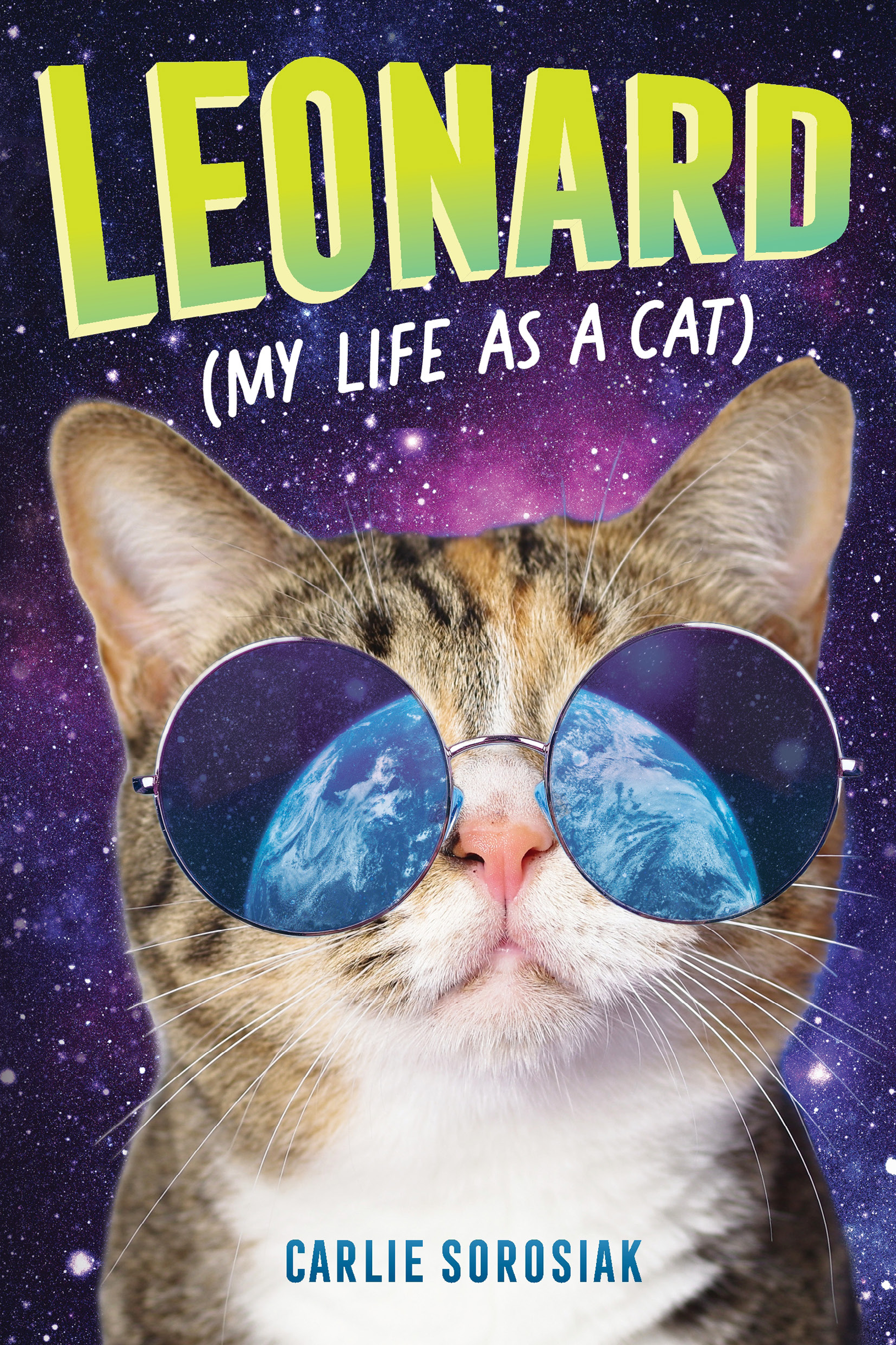

Humans have it all wrong about aliens. Sometimes I see images of us on televisionwith enormous eyes, with skin the color of spring leavesand I wonder: Who thought of this? What reason could they have? Olive always tells me not to watch those shows. Youll just give yourself bad dreams, she says. So we switch off the TV and curl up by the window, listening to the gentle hush of waves.

But the truth is, I really dont belong herenot permanently, not forever. Thats why were traveling in this Winnebago, zooming down dark roads at midnight. Olive is wearing her frayed overalls, and shes cradling me in her arms.

I dont squirm. I dont scratch. I am not that type of cat.

You wont forget me, she says, pressing her forehead to mine. Please promise you wont.

She smells of cinnamon toast and raspberry shampoo. There are daisy barrettes in her hair. And for a second, I consider lying to herout of love. The words are right there: I will always remember. I could never forget. But Ive been honest with her this whole time, and the rules of intergalactic travel are clear.

Tomorrow, I will forget everything Ive ever felt.

In my mind, Olive will exist only as data, as pure information. Ill remember her daisy barrettes, our Saturday afternoons by Wrigley Pierbut not how it felt to share a beach towel, or read books together, or fall asleep under the late June sun. And Olive doesnt deserve that. She is so much more than a collection of facts.

Halfheartedly, I summon a purr. It rattles weakly in my chest.

You get to go home, Olive says, the ghost of a smile on her face. Home.

The Winnebago speeds faster, then faster still. Outside, the sky is full of stars. And I want to communicate that I will miss thisfeeling so small, so earthly. Am I ready to go back? Half of me is. And yet, when I close my eyes, I picture myself clinging to the walls of this motor home.

Olive sets me down on the countertop, the plastic cool under my paws. Opening her laptop, she angles the keyboard toward me, a gesture that says, Type, will you? But I shake my head, fur shivering.

You dont want to talk? she asks.

What can I say? I owe it to Olive not to make this any harder. So I wont use the computer. I wont tell her what Ive been hopingto maybe carry one thing back. Maybe if I concentrate hard enough, a part of Olive will imprint on a part of me, and I will remember how it felt. How it felt to know a girl once.

Okay, she says, shutting her laptop with a sigh. At least eat your crunchies.

So I eat my crunchies. Theyre trout-flavored and tangy on my tongue. I chew slowly, savoring the morsels. This is one of my last meals as a cat.

I havent always lived in this body. Leonard wasnt always my name.

Olive pats my head as I lick the bowl clean. I know you didnt want to be a cat, she says, so softly that my ears prick to hear her, but you are a very, very good cat.

I want the computer now. My paws are itching to type: You are a very, very good human. Because she is. And she will be, long after Im gone.

If you allow yourself, you might like our story. Its about cheese sandwiches and an aquarium and a family. It has laughter and sadness and me, learning what it means to be human.

On my journey to Earth, I was supposed to become human.

That is where Ill begin.

For almost three hundred years, I had wished for hands. Every once in a while, I pictured myself holding an object in my own palm, with my own fingers. An apple, a book, an umbrella. Id heard the most wonderful rumors about umbrellasand rain, how it dotted your skin. Humans might take these things for granted (standing in the street, half shielded by an umbrella in a summer rainstorm), but I promised myself, centuries ago, that I would not.

It was all just so tremendously exciting, as I hitched a ride on that beam of light.

This trip to Earth was about discovery, about glimpsing another way of life.

And I was ready.

On the eve of our three hundredth birthdays, all members of our species have the opportunity to spend a month as an Earth creatureto expand our minds, gather data, and keep an eye on the neighbors. I couldve been a penguin in Antarctica or a wild beast roaming the plains of the Serengeti; I couldve been a beluga whale or a wolf or a goose. Instead, I chose the most magnificent creature on Earth: the common human.

Perhaps you find my decision laughable. I feel the need to defend it. So please think about penguins, who refuse to play the violin. About wolves, who have no use for umbrellas. Even geese take little joy in the arts. But humans? Humans write books, and share thoughts over coffee, and make things for absolutely zero reason. Swimming pools, doorbells, elevatorsI was dying to discover the delight of them all.

Still, it was a terrifically difficult choice, narrowing it down. Because there are so many different types of humans. Did I want to wear shorts and deliver mail? Would a hairnet look flattering on me? Could I convincingly become a television star? After nearly fifty years of thought, I decided on something humbler. More suited to my interests.

A national park ranger. A Yellowstone ranger. Wasnt it perfect? Id give myself a mustache and boots and have a dazzling twinkle in my left eye. In my mind, Id practiced the way Id flick my wristsId have wrists, you seetoward the natural exhibits. In front of a crowd of human tourists, Id walk with an exaggerated swing of my hips and carry many useful things in my pockets: a Swiss Army knife, a butterfly net, a variety of pens for writing. Humor is a valued trait among humans, so for an entire year, I exclusively prepared jokes.

How many park rangers does it take to change a light bulb? Twenty-two. Do you get it? Twenty-two! (I wasnt entirely sure that I understood humor; my species is pure energy and cant exactly feel in our natural state. But wasnt there something inherently funny about the curve of a two, let alone two twos?)

Setting off from my home planet, I imagined the feeling of laughter, how it might rattle my belly. It was a nice distraction, considering the strangeness of it all. My species is a hive mind, meaning we think and exist as one, like drops in the ocean of Earthand I wasnt prepared for the sensation of leaving them. There was a quiet pop as we separated. Then I was alone, for the first time in three hundred years.

Honestly, I wasnt entirely sure what to do with myself. In the distance were the crystallized mountains of my planet, rivers of helium gleaming under stars, and all I could summon was a single thought: For now, goodbye.

The beam of light hummed as I latched on.

To kill time on the journey, I practiced more jokes. Why did the chicken cross the road? Because he was genetically hardwired as an Earth creature to do so. Knock-knock?