Photo on page 35 courtesy AP Photo/Julio Cortez.

Photo on page 38 courtesy AP Photo/Jessica Hill.

All other photographs courtesy of the author.

2017 Alissa Parker

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, Ensign Peak, at permissions@shadowmountain.com. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of Ensign Peak.

Visit us at shadowmountain.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

(CIP on file)

ISBN 978-1-62972-279-5

Printed in the United States of America

Edwards Brothers Malloy, Ann Arbor, MI

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

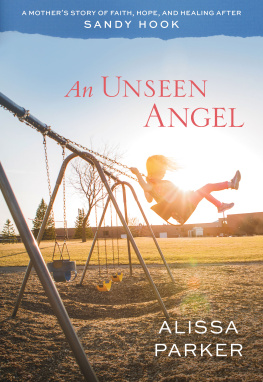

Cover image credits:

Book design Ensign Peak

Art direction: Richard Erickson

Cover design: Heather G. Ward

Interior design: Shauna Gibby

Cover photo: Annie Otzen/Getty Images

Photograph of Emilie courtesy of the author

For Emilie

You helped me see the beautiful connections that bind us together forever.

And for Madeline and Samantha

This book is my gift to you. I hope you always remember the love you shared with your sister.

Prologue

March 23, 2013

Newtown, Connecticut

I looked out the bay window of my living room and my heart started pounding. A grey Connecticut State Police SUV had just eased to a stop in the driveway. My husband, Robbie, put his arm around my shoulder, as if to say, Its going to be all right. But I wasnt all rightI was anxious, queasy, and frightened. It had been three months since twenty first-grade children and six adults had been killed by a lone gunman at Sandy Hook Elementary School. My daughter Emilie was one of those victims. Their investigations now complete, the police were here to return the clothes she had been wearing at the time of the shooting.

One of the officers, a woman I knew well by now, started down our stone walkway. Shortly after the shooting I had talked to her on the telephone about what Emilie had worn that daya dark pink shirt, a pink pleated skirt with ruffles, pink leggings, and black and pink snow boots. Emilie loved pink, I told her. Many times since then she had respectfully walked me through the grim details of the police investigation, one of the hardest ordeals of my life. When the investigation concluded, I requested Emilies personal items, and she promised to hand-deliver them to our home.

Robbie opened the front door and said hello. I expected the officer to hand me a sealed bag with the word EVIDENCE on it. Instead she was holding a child-sized trunk. It was white with pink polka dots, and it had a rounded lid fastened with a metal latch. She carried it by the pink rope handles on the sides. A note the size of a business card was tied to a pink bow on top.

She handed the trunk to Robbie, who removed the note, and we read:

How lucky I am to have something

that makes saying good-bye so hard.

A.A. Milne

Our eyes welled up. By the time we looked up to thank the officer, she was gone. We watched her drive off, then sat on our living-room sofa, the trunk resting on our laps. With sunlight streaming through the window, we looked at each other and, without saying a word, we each knew what the other was feelingapprehension. Are we really ready to see how our daughter was murdered?

Robbie slowly opened the lid of the little trunk, and the fresh scent of laundry detergent emerged. Emilies clothes were neatly folded. It was almost as if someone had tried to wash away all traces of that awful day. My eyes were immediately drawn to the item on topa purple fleece scarf that my mother had made for Emilie just one week before the shooting. I had forgotten about it until I saw it in the trunk. My mind went back to that morning in December when I had stood in the living room with Emilie, wrapping the scarf around her neck and tying it in a knot before she headed for the bus stop. She had worn that scarf all week long. It was her way of adding a fashionable accent to her outfits.

Robbie removed it from the trunk and unfolded it, and instantly I convulsed. The scarf had six bullet holes. Nauseous, I took the scarf from Robbie and ran my index finger over the holes. Then I arranged it just as I had done that morning for Emilie. When I bunched up the fabric I realized that the six holes represented the trajectory of a single bullet passing through the folds of fleece wrapped around her neck. I realized that it was probably the shot that killed my child. I looked at Robbie and we cried.

In the aftermath of the shooting I was desperate to know the details of what had happened to Emilie. Facts, I desperately hoped, would lead to understanding, to the bleak necessity of closure. Still, I kept these facts at an emotional arms length. For instance, I had chosen not to look at Emilies body at the funeral home before the mortician dressed her for the closed-casket memorial service. My last memory of Emilie was a happy one of her innocently running for the school bus, and I refused to replace that sunny image of her with anything more disturbing. I got through each day by considering the violence in her classroom as something abstract. That was my coping mechanism. I didnt want to think too deeply about what happens when a semiautomatic rifle is used to fire round after round of ammunition into a classroom of first graders, so I blocked those images from my mind.

Going through Emilies clothes in the chest presented me with the undeniable, concrete reality of what had happened to our daughter. There was nothing abstract about the frayed strands of fabric around the holes. No amount of laundry detergent could expunge the proof of violence. The other items in the trunkespecially her shirt, which was sprayed with holesconfirmed the unthinkable. One moment I was putting my little girl on the school bus at the end of our road. An hour later, a man that my daughter had never mettwenty-year-old Adam Lanzaentered her classroom, pointed a gun at her, and pulled the trigger. Again. And again. And again. There was no getting around that fact. My six-year-old daughter didnt simply pass away on December 14, 2012. She was brutally murdered in the second deadliest school shooting by a lone individual in American history.

Writing a book about losing Emilie wasnt something I had planned to do. To begin with, Im very private and reserved. Also, after Emilie died I couldnt bear to think about what had happened to her, much less write about it. Nor, I believe, do most people want to read about something so sad. But violence, grief, and loss are not what this book is primarily about; at least, I prefer not to look at it that way. Although it contains tragedy, my story is ultimately not tragic. The story I feel compelled to share is one of help and healing. It is a story of how Gods love and protection surrounded me during my darkest hour.

I have always believed that family is eternal, that we are bound with our loved ones by a tie that outlasts disaster and death. But when Emilie died, my faith in this principle was put to the ultimate test. I asked God again and again to help me feel Emilies presence, to confirm that she still was with me and that our family was and is forever connected. In His own time, He gave me this reassurance. I was granted very sacred personal experiences that allowed me to see and feel Emilie in the small and simple occurrences of daily life. I have no doubt whatsoever that Emilie lives, that she is still a part of my family, and that we will be reunited in Gods time.