Preface

Being out

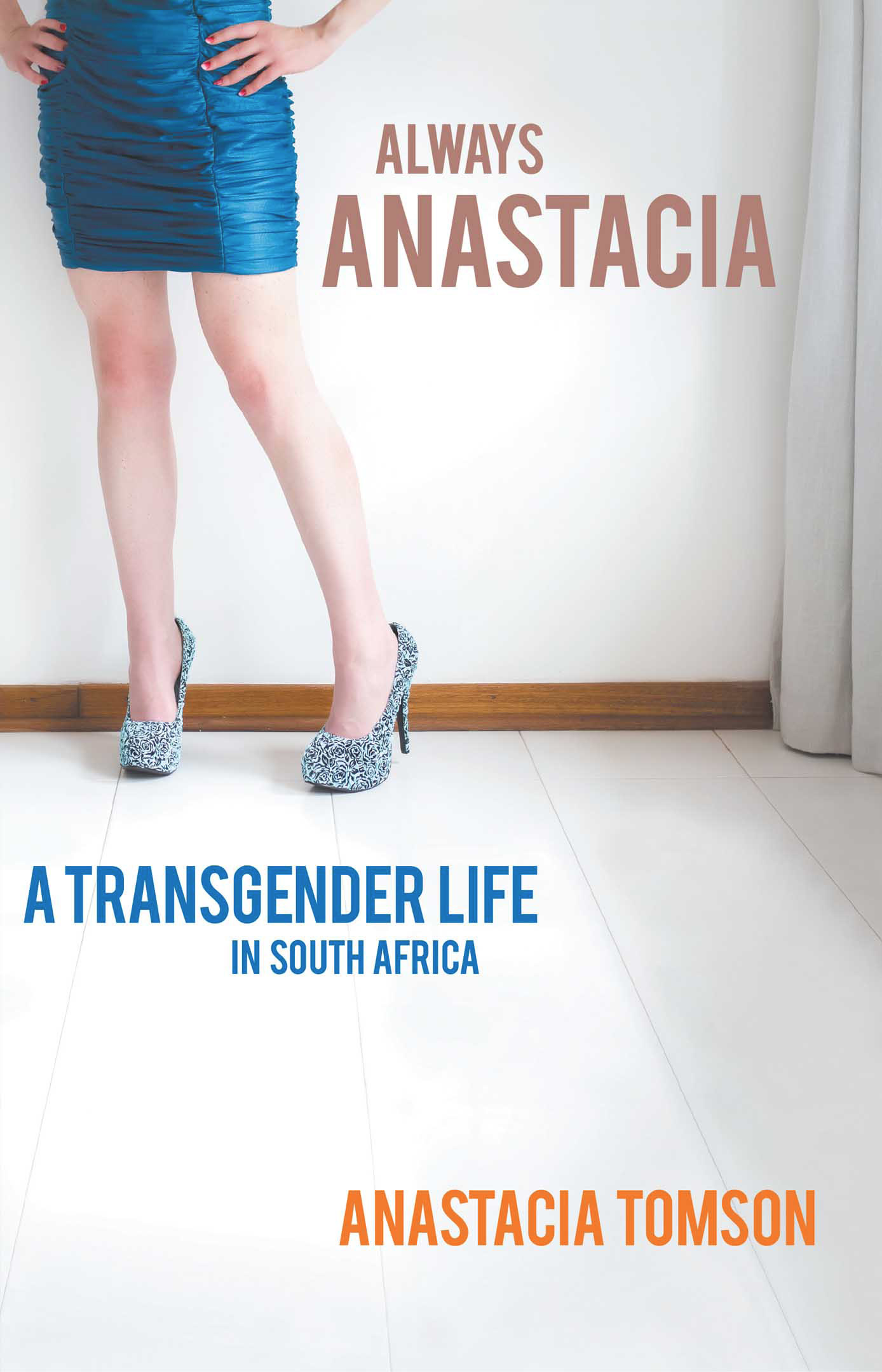

When I first understood that I needed to transition in order to live, I started thinking about the kind of life that I would pursue. Specifically, I spent much time thinking about the prospect of going stealth.

It was a real temptation, the idea of packing my bags and disappearing to some other town with no ties to the life I had pretended to live. Leaving behind my old name, my traumatic childhood, my confusing adolescence, and those first hollow years of my adult life.

I could settle somewhere new, where no one would recognise me.

Transition is a gruelling process. There is hardship at every turn: dealing with ignorant and insensitive health-care professionals to gain access to treatment, trying to convince government departments to amend identity documents, fighting against a conservative society that would sooner write people off as freaks than try to understand their struggles or ease their strenuous journeys.

Many people act as if they have rights to transgender peoples bodies, asking us intimate and inappropriate questions and expecting answers. Some touch without permission, and become offended when we rebuke them. People fixate and quiz us on our sexuality. They ask after our genitalia, whether weve had surgical procedures, whether we intend to. How we knew, whom weve told, whether we sit or stand to pee, how we have sex. Transgender people who wish just to sink into anonymity and live the peaceful life for which they have fought have my unending empathy and respect.

There was a time when I wanted that too when I used to say that I was not an activist. That I did not need to make my voice heard to make a difference. I was content to initiate change through my work, and felt that my activism was quiet and non-confrontational.

But, as I grew more confident in my identity, I discovered that not only did I have a voice, but that it insisted on making itself heard. I was a proud woman and a proud feminist. Discrimination and oppression based on gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or race had always worried me, but I had never known how to address them. I had never felt that I had the agency to speak out, or anything worth saying.

As my self-respect grew, I re-examined my priorities. I wanted to live the life that I felt I deserved, in peace. But I also wanted people to understand the lengths to which I had gone to be seen for who I was. I was not ashamed of being trans, and I did not want to have to live in fear of my secret being discovered someday.

I knew there would be a price that to make some kind of difference to those who faced struggles similar to mine, Id have to lay bare the intimate details of my life. But I knew, also, that doing so would bring me freedom. My dark secret could hold no power over me if it wasnt a secret at all.

So, I made my decision. I came out first individually, to friends and family, and then to the world. I made no attempts to hide who or what I was. It was not easy, but embracing my truth has allowed me to strengthen so many of my bonds and relationships. Of course, a few have suffered. Some friends, even ones who are mentioned in this book, have grown distant from me. Some of them still associate with me, though our dynamic has shifted irrevocably; others refuse to talk to me at all. But my connection with those who have stood by me is stronger than ever.

I chose to combat prejudice and hatred with empathy and understanding. I am many things: a woman, a friend, a doctor, a confidant. I am transgender. Sometimes I am afraid and overwhelmed. I am a human being, and these are my experiences. I hope you enjoy sharing them my pain and my happiness.

I entrust my secrets to you. All I ask for in return is your compassion.

With pride

Day 0, 1 July 2015

I rub the sleep from my eyes as I open them, squinting at the bedside clock. Eight oclock earlier than I expected it to be. The first weekday morning in a long time that I havent been roused by an alarm clock. The sensation is novel.

I feel the morning chill of the Johannesburg winter against my face, as the scent of freshly brewed coffee wafts from the kitchen into my bedroom. I am grateful that I neglected to turn off the timer switch, despite my plans to sleep in. I gaze briefly at the bare, off-white walls of my bedroom, reminding myself that I still havent got around to hanging the prints of the wildlife photographs I used to take while working in Mpumalanga four years ago.

As I crawl out of bed, it takes a few moments for the reality to settle in: today is the first day that I am free of the expectations of maleness to which I have been subject for so many years. For months, I had been presenting exclusively as female in every setting barring my workplace. My job has been the last outpost of that old shell of a life.

I pull back the curtains and stare, for a moment, out my bedroom window, watching the palm trees in my neighbours yard swaying in the breeze. The feeling is surreal: that I no longer have to act every day, switching back and forth between voices, mannerisms, vocabulary. That I am free to live the life I believed would never be mine to live. It is overwhelming. I feel relief, but even so, I know that I cant comprehend just how enormous this change has been.

Yesterday was my last evening at the practice. It was heart-wrenching and bittersweet. I left without fanfare, without the opportunity to say my goodbyes properly. That chapter of my life ended anticlimactically, with a whimper far more than a bang. I still feel that I need closure, but that will have to wait for another time. Right now, I am just relieved to be absolved of that job and its responsibilities.

I stand in front of the mirror as I remind myself that I no longer have to wear the uniform. I can grow my nails, and paint them. I am free, finally, to have my ears pierced. I can use the voice that Ive spent so many hours meticulously cultivating with Michelle, my speech therapist. I no longer have to hide my disgust at being called boet or sir, or tolerate any references to my deadname.

I have fought hard, held back for decades by a body that did not fit and an identity that did not belong. At first, it had seemed like transition was a vague and unattainable aspiration, a romantic ideal that was incompatible with reality. But now after five months of hormone therapy, countless sessions of painful laser hair removal and multiple appointments with doctors and psychologists it is very much a reality.

This is far from the end of the road, however. Hormone therapy will be lifelong. At some stage, I envision perhaps undergoing surgery, or surgeries. I continue to wait for the Department of Home Affairs to make the changes to my name official and to amend my legal gender. But none of these details seem to matter terribly much in the face of my new-found freedom. Transition is no fanciful daydream it is the life that I am living, and no longer has to share its time with falsehood.