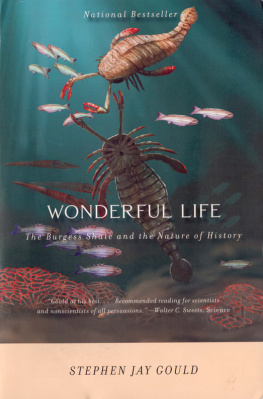

Wonderful Life

To NORMAN D. NEWELL

Who was, and is, in the most noble

word of all human speech, my teacher

Contents

This book, to cite some metaphors from my least favorite sport, attempts to tackle one of the broadest issues that science can addressthe nature of history itselfnot by a direct assault upon the center, but by an end run through the details of a truly wondrous case study. In so doing, I follow the strategy of all my general writing. Detail by itself can go no further; at its best, presented with a poetry that I cannot muster, it emerges as admirable nature writing. But frontal attacks upon generalities inevitably lapse into tedium or tendentiousness. The beauty of nature lies in detail; the message, in generality. Optimal appreciation demands both, and I know no better tactic than the illustration of exciting principles by well-chosen particulars.

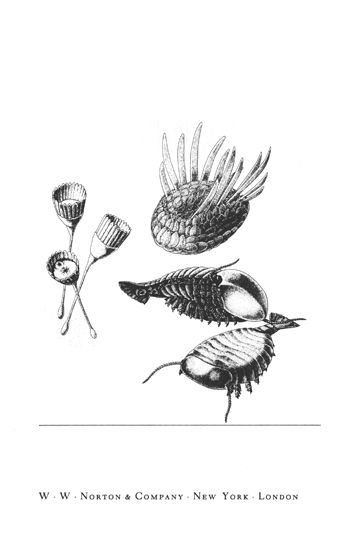

My specific topic is the most precious and important of all fossil localitiesthe Burgess Shale of British Columbia. The human story of discovery and interpretation, spanning almost eighty years, is wonderful, in the strong literal sense of that much-abused word. Charles Doolittle Walcott, premier paleontologist and most powerful administrator in American science, found this oldest fauna of exquisitely preserved soft-bodied animals in 1909. But his deeply traditionalist stance virtually forced a conventional interpretation that offered no new perspective on lifes history, and therefore rendered these unique organisms invisible to public notice (though they far surpass dinosaurs in their potential for instruction about lifes history). But twenty years of meticulous anatomical description by three English and Irish paleontologists, who began their work with no inkling of its radical potential, has not only reversed Walcotts interpretation of these particular fossils, but has also confronted our traditional view about progress and predictability in the history of life with the historians challenge of contingencythe pageant of evolution as a staggeringly improbable series of events, sensible enough in retrospect and subject to rigorous explanation, but utterly unpredictable and quite unrepeatable. Wind back the tape of life to the early days of the Burgess Shale; let it play again from an identical starting point, and the chance becomes vanishingly small that anything like human intelligence would grace the replay.

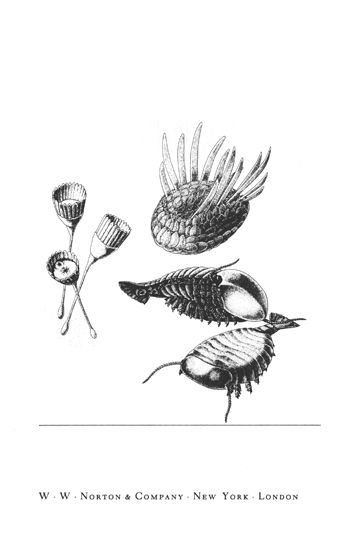

But even more wonderful than any human effort or revised interpretation are the organisms of the Burgess Shale themselves, particularly as newly and properly reconstructed in their transcendent strangeness: Opabinia, with its five eyes and frontal nozzle; Anomalocaris, the largest animal of its time, a fearsome predator with a circular jaw; Hallucigenia, with an anatomy to match its name.

The title of this book expresses the duality of our wonderat the beauty of the organisms themselves, and at the new view of life that they have inspired. Opabinia and company constituted the strange and wonderful life of a remote past; they have also imposed the great theme of contingency in history upon a science uncomfortable with such concepts. This theme is central to the most memorable scene in Americas most beloved filmJimmy Stewarts guardian angel replaying lifes tape without him, and demonstrating the awesome power of apparent insignificance in history. Science has dealt poorly with the concept of contingency, but film and literature have always found it fascinating. Its a Wonderful Life is both a symbol and the finest illustration I know for the cardinal theme of this bookand I honor Clarence Odbody, George Bailey, and Frank Capra in my title.

The story of the reinterpretation of the Burgess fossils, and of the new ideas that emerged from this work, is complex, involving the collective efforts of a large cast. But three paleontologists dominate the center stage, for they have done the great bulk of technical work in anatomical description and taxonomic placementHarry Whittington of Cambridge University, the worlds expert on trilobites, and two men who began as his graduate students and then built brilliant careers upon their studies of the Burgess fossils, Derek Briggs and Simon Conway Morris.

I struggled for many months over various formats for presenting this work, but finally decided that only one could provide unity and establish integrity. If the influence of history is so strong in setting the order of life today, then I must respect its power in the smaller domain of this book. The work of Whittington and colleagues also forms a history, and the primary criterion of order in the domain of contingency is, and must be, chronology. The reinterpretation of the Burgess Shale is a story, a grand and wonderful story of the highest intellectual meritwith no one killed, no one even injured or scratched, but a new world revealed. What else can I do but tell this story in proper temporal order? Like Rashomon, no two observers or participants will ever recount such a complex tale in the same manner, but we can at least establish a groundwork in chronology. I have come to view this temporal sequence as an intense dramaand have even permitted myself the conceit of presenting it as a play in five acts, embedded within my third chapter.

Chapter I lays out, through the unconventional device of iconography, the traditional attitudes (or thinly veiled cultural hopes) that the Burgess Shale now challenges. Chapter II presents the requisite background material on the early history of life, the nature of the fossil record, and the particular setting of the Burgess Shale itself. Chapter III then documents, as a drama and in chronological order, this great revision in our concepts about early life. A final section tries to place this history in the general context of an evolutionary theory partly challenged and revised by the story itself. Chapter IV probes the times and psyche of Charles Doolittle Walcott, in an attempt to understand why he mistook so thoroughly the nature and meaning of his greatest discovery. It then presents a different and antithetical view of history as contingency. Chapter V develops this view of history, both by general arguments and by a chronology of key episodes that, with tiny alterations at the outset, could have sent evolution cascading down wildly different but equally intelligible channelssensible pathways that would have yielded no species capable of producing a chronicle or deciphering the pageant of its past. The epilogue is a final Burgess surprisevox clamantis in deserto, but a happy voice that will not make the crooked straight or the rough places plain, because it revels in the tortuous crookedness of real paths destined only for interesting ends.

I am caught between the two poles of conventional composition. I am not a reporter or science writer interviewing people from another domain under the conceit of passive impartiality. I am a professional paleontologist, a close colleague and personal friend of all the major actors in this drama. But I did not perform any of the primary research myselfnor could I, for I do not have the special kind of spatial genius that this work requires. Still, the world of Whittington, Briggs, and Conway Morris is my world. I know its hopes and foibles, its jargon and techniques, but I also live with its illusions. If this book works, then I have combined a professionals feeling and knowledge with the distance necessary for judgment, and my dream of writing an insiders McPhee within geology may have succeeded. If it does not work, then I am simply the latest of so many victimsand all the clichs about fish and fowl, rocks and hard places, apply. (My difficulty in simultaneously living in and reporting about this world emerges most frequently in a simple problem that I found insoluble. Are my heroes called Whittington, Briggs, and Conway Morris; or are they Harry, Derek, and Simon? I finally gave up on consistency and decided that both designations are appropriate, but in different circumstancesand I simply followed my instinct and feeling. I had to adopt one other convention; in rendering the Burgess drama chronologically, I followed the dates of publication for ordering the research on various Burgess fossils. But as all professionals know, the time between manuscript and print varies capriciously and at random, and the sequence of publication may bear little relationship to the order of actual work. I therefore vetted my sequence with all the major participants, and learned, with pleasure and relief, that the chronology of publication acted as a pretty fair surrogate for order of work in this case.)

Next page