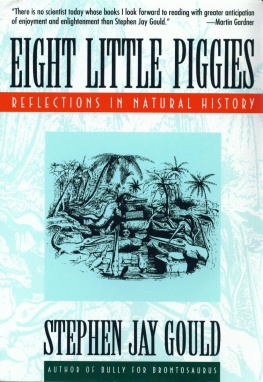

Treasures and Oddities of Natural History Collectors from Peter the Great to Louis Agassiz (with R. W. Purcell)

The Flamingos Smile

Reflections in Natural History

Stephen Jay Gould

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Losing the Edge originally appeared in Vanity Fair in March, 1983. Reprinted by kind permission.

Strike Three for Babe originally appeared in The New York Times on November 19, 1984, as The Strike That Was Low and Outside.

Copyright 1984 by The New York Times Company. Reprinted by permission.

SETI and the Wisdom of Casey Stengel originally appeared in Discover Magazine , Time, Inc., in March 1983. Reprinted by kind permission.

Sex, Drugs, Disasters, and the Extinction of Dinosaurs originally appeared in Discover Magazine , Time, Inc., in March 1984. Reprinted by kind permission.

Copyright 1985 by Stephen Jay Gould

All rights reserved.

First published as a Norton 1987

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Gould, Stephen Jay.

The flamingos smile.

1. Natural historyEssays.

I. Title.

QH81.G673 1985 508 85-4916

ISBN: 978-0-393-30375-9

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10110

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

10 Coptic Street, London WC1A 1PU

F OR D EB

for everything

Contents

Reversals

Boundaries

Two Admirable Creationists

The Cloven Hoofprint of Theory

The Chain of Being

Eugenics Past and Present

The Flamingos Smile

Prologue

IN THE MEDIEVAL GLASS of Canterbury Cathedral, an angel appears to the sleeping wise men and warns them to go straight home, and not return to Herod. Below, the corresponding event from the Old Testament teaches the faithful that each moment of Jesus life replays a piece of the past and that God has put meaning into timeLot turns round and his wife becomes a pillar of salt (the white glass forming a striking contrast with the glittering colors that surround her). The common theme of both incidents: dont look back.

The Flamingos Smile is my fourth volume of essays from monthly columns in Natural History Magazine; it also contains my hundredth contribution to a genre that I once considered both more ephemeral and impossible to sustain. Thus, I will also break Lots injunction, hope for a sweeter fate, and look back upon the previous volumes.

One brand of Scotch often graces New Yorker back covers with its claim that Angus Mac-somebody-or-other (and ancestors of that ilk) have been throwing the caber on the same field since 1367, give or take a few years. Some things never change, the bottom line (literally) proclaims. Some things better change (however difficult under punctuated equilibrium), if only to allay boredom, but fundamental themes (like a successful blend) should revel in persistence. If my volumes work at all, they owe their reputation to coherence supplied by the common theme of evolutionary theory. I have a wonderful advantage among essayists because no other theme so beautifully encompasses both the particulars that fascinate and the generalities that instruct.

Evolution is one of the half-dozen shattering ideas that science has developed to overturn past hopes and assumptions, and to enlighten our current thoughts. Evolution is also more personal than the quantum, or the relative motion of earth and sun; it speaks directly to the questions of genealogy that so fascinate ushow and when did we arise, what are our biological relationships with other creatures? And evolution has built all those creatures in stunning varietyan endless source of delight (though not the reason for their existence!), not to mention essays.

To map the changes within this persistence, I reread the prefaces to my other volumes and found a coordinating theme, linked to times of composition, for each. Ever Since Darwin , as a first attempt, presented the basics of evolutionary theory as a comprehensive world view with implications for a political world (of years just following the Vietnam War) that treated human diversity more generously. The Pandas Thumb highlighted a series of debates (about rates and results) that arose among professional evolutionists and imparted renewed vigor and range to this view of life. Hens Teeth and Horses Toes appeared in the shadow of resurgent Yahooismso-called creation science as preached by Falwell and companyand required a gentle defense of both the veracity and humanity of evolution.

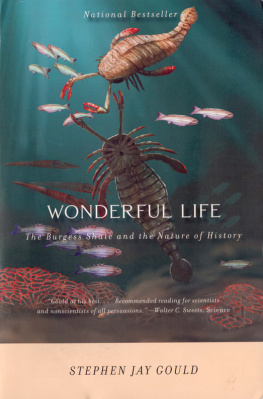

The Flamingos Smile has a different kind of triggera specific discovery with cascading implications. It now seems, to use the favored jargon of the profession, highly probable that an errant asteroid or shower of comets provoked the great Cretaceous extinction (dinosaur death knell and, conversely, the Introit for our own evolution). Moreover, such quintessentially fortuitous and episodic restructurings of life have occurred several times, perhaps even on a regular cycle of some 2530 million years. The particulars are striking (pun intended, I suppose), but the general implications are even more arresting, and beautifully coincident with persistent themes that infest all my columnsthe meaning of pattern in lifes history (partly random and, in any case, not designed for us or towards us); the social implications of scientific assaults upon pervasive biases of Western thought (my favorite four horsemen of progress, determinism, gradualism, and adaptationismall severely questioned by the impact theory of mass extinction). At the center stands the one theme that transcends even evolution itself in generalitythe nature of history. The Flamingos Smile is about history and what it means to say that life is the product of a contingent past, not the inevitable and predictable result of simple, timeless laws of nature. Quirkiness and meaning are my two not-so-contradictory themes.

All this sounds awfully tendentious and may lead readers to fear that potential pleasure has been sacrificed on a bloated altar of imagined importance (my volumes have become progressively longer for an unchanging number of essaysa trend more regular than my mapped decline of batting averages from essay 14, and a warning signal of impending trouble if continued past a limit reached, I think, by this collection). My potential salvation in the face of admitted egotism must remain an unswerving commitment to treat generality only as it emerges from little things that arrest us and open our eyes with ahawhile direct, abstract, learned assaults upon generalities usually glaze them over. Even my most grandiloquent essay (emphatically not my best)number 29 on continuity itselfarose as a gloss on a small observation: the mingling of sacred and profane in the iconography of Pio Quatros Palace in the Vatican.

I placed my essays on reversals and boundaries (part 1) at the beginning because they best exemplify this style of letting generality cascade out of particularsthree essays on inversions of general expectations (flamingos that feed upside down; female insects that supposedly eat their mates after copulation; flowers and snails that change from male to female, and sometimes back again); and two on continua and the problem of boundaries in nature (are Portuguese men-of-war individuals or colonies, are Siamese twins one person or two). Each essay is both a single long argument and a welding together of particulars.