W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Eight Little Piggies: reflections in natural history / Stephen Jay Gould.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Natural historyPhilosophyPopular works. 2. Evolution (Biology)Popular works. I. Title.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

A Reflective Prologue

THESE ESSAYS , volume six in a continuing series, confront history on the broadcast scale of lifes evolution during 3.5 billion years. Since macrocosms are fractals of microcosms, the series also records a personal history. In the sweetest introduction I have ever received (for a talk at the Academy of Natural Sciences in San Francisco) former major league ballplayer and current ecoactivist Bruce Bochte recounted my article on why Joe DiMaggios 56 game hitting streak is the greatest accomplishment in the history of baseball (see Essay 31 in Bully for Brontosaurus ). He then pointed out that I was working on a 208 monthly essay streak, also unbroken since its inception in January 1974. Over such a long stretch of adulthood, ranging from relative youth (in my early thirties) to distinct middle age (I just passed the half-century mark), many passages must be noted as the ineluctable changes of life unfold. Two aspects of ontogeny seem especially relevant to this continuing series.

First, Eight Little Piggies is a book of middle life, and it does contrast, entirely favorably I think (but I am no longer talking to my thirtysomething self), with my youthful Ever Since Darwin . I suppose that the major sign of this particular passage lies in my exploration of a traditional essay genre that I had previously shunnedthe contemplative and highly personal ruminations in Section 4, Musings. These essays, on memory, persistence, and authenticity, talk about the importance of unbroken connections within our own lives and to our ancestral generationsa theme of supreme importance to evolutionists who study a world in which extinction is the ultimate fate of all and prolonged persistence the only meaningful measure of success.

These essays may treat familiar themes, but at least they follow my idiosyncratic procedure of building, via oddly tangential connections, from a small and concrete item or incident to a broad generalityfrom sitting with my grandfather on some warehouse steps to characteristic pathways of false memory in our favorite stories (Essay 11); from a graveyard and the invisibility of a large factory in Amana, Iowa, to our need for bucolic myths and the false concept of past golden ages (Essay 12); from calling cards and a visit with a 97-year-old paleontologist who knew C. D. Walcott to the importance we place on continuity and nonvicarious experience (Essay 13); and from a breakfast in San Francisco to a taxonomy of authenticity and the role of vernacular customs and architectures in the preservation of regional diversity (Essay 14). All these essays feature our treatment and distortion of historical recordsa kind of ultimate subject for any paleontologist!

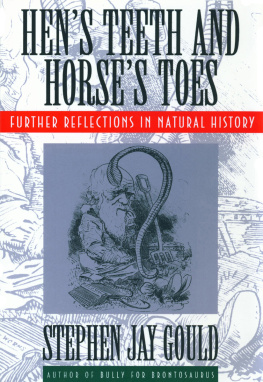

Second, the six volumes form a sensible series, each with a different central focus appropriate to its time in three ways: stage in my own life, reaction to current events, and position in the developing logic of an extended discourse on evolution and history. The first volume, Ever Since Darwin (1977), centers upon the basic explication of Darwinian principles (where else would one start?). The Pandas Thumb (1980) develops the largely unrecognized extensions and corrections of Darwinism that run so counter to many sociocultural hopes and expectations (as in the principle of imperfection embodied in the title example). Hens Teeth and Horses Toes (1983) had an immediate focus that now, and happily, seems a bit outdated (but by no means dead)the attack of creation science (biblical literalism) upon teaching evolution, and our victories both in courtrooms and in cogent and decent argument. The Flamingos Smile (1985) emphasizes the importance of randomness and unpredictability in the history of life. This theme had a double and immediate origin at two levelsmy own bout with cancer at the most personal, and the proposal and successful development of the asteroidal impact theory of mass extinction at the broadest and most general. Bully for Brontosaurus (1991), following a longer gap for rumination and synthesis, then put the two central themes togetherthe mechanics of Darwinism with the unpredictability of complex temporal sequencesto form, finally, a full scale disquisition on the nature of history and its primary theme of contingency (also explored in my intervening Wonderful Life , 1989).

I like to think of these volumes as building rather than replacing. The old foci carry over and weave together, tightening up thereby and leaving room for new extensions. Yet one theme of transcendent (and growing) importance has been almost absent (and shamefully so) from my writings heretofore. How can any naturalist, any self-professed lover of diversity, ignore the subject of anthropogenic environmental deterioration and massive extinction of species on our present earth? Oh, I have not entirely bypassed this central concern of my profession. Side comments and paragraphs abound, and even a full essay or two (Essay 29 on nuclear winter in The Flamingos Smile , for example). But I have never addressed this theme centrally and head on.

My reluctance reflects no failure of strong feelings. Quite the contrary. If anything, I have desisted because my feelings are too powerfullying in the domain that Wordsworth described as thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears (and perhaps for words as well). I had never found any distinctive words to convey these common emotions. I could not bear merely to write the shibboleths of the movementor, even worse, to emote for show, catharsis, or accountability, but with nothing different to add to the hyperabundance of current expostulations.

Perhaps I have finally found something to say that might be helpful, rather than only repetitive. Eight Little Piggies includes a sectionplaced primus inter pares on the sadness of anthropogenic destruction. But if I have finally found a voice, I came to it in my usual wayentirely unanticipated and via a quirky item arising from a personal experience then adumbrated along a forest of tangents. I went to French Polynesia with my son in the summer of 1991 and learned that the island of Moorea had served as the model for Rogers and Hammersteins Bali Hai of South Pacific . I also knew that Moorea, and other adjacent islands, had recently experienced a tragically unnecessary extinction of a large, beautiful, and historically important fauna of land snails (the genus Partula ) that had been the lifes work of Henry Crampton, a great scholar of land snails who was revered within the profession, if unknown outside. (My technical research is on land snails, so this is my community.)