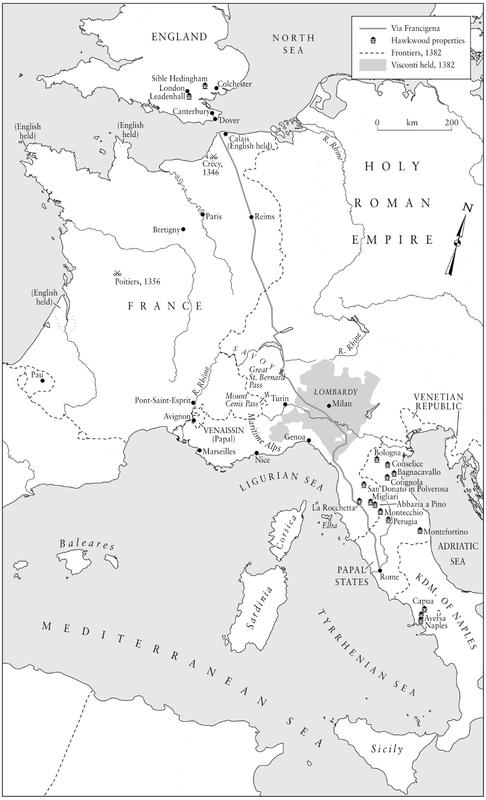

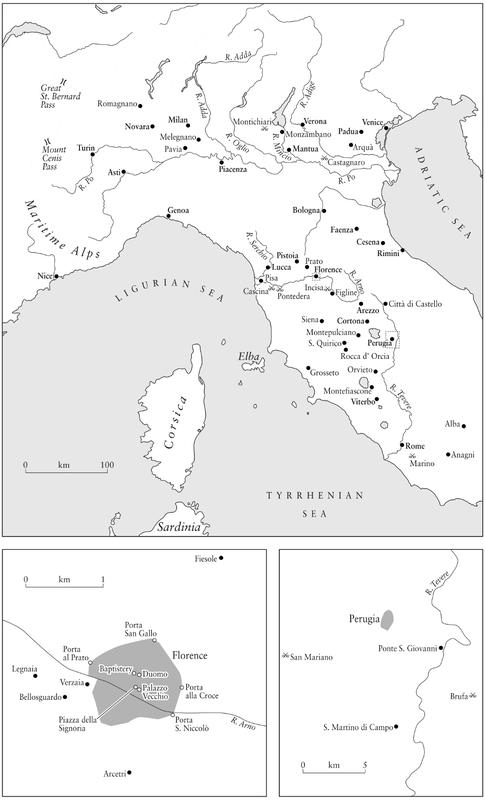

Northern and Central Italy showing the city-states.

I first heard of John Hawkwood in a conversation with Muriel Spark and Penelope Jardine that took place in Penelopes house near Monte San Savino in 1989. The first few shoeboxes of research were collected as a result of their initial encouragement, for which I would like to thank them. Ten years later, I mentioned the project to my editor Neil Belton, who convinced me to revive it. Since then, his enthusiasm has never waned, and his critical insights have proved indispensable. My agent, Felicity Rubinstein, has also given invaluable support. The book was read in draft form by Luke Syson, of the National Gallery, London; Terry Jones, author of Chaucers Knight; Peter Coss, Professor of Medieval History at Cardiff University; and Jonathan Sumption, QC, historian of the Hundred Years War. For their comments and corrections, I am very grateful. Any remaining errors are my own.

I started writing this book while Arts Editor at the New Statesman. My thanks to the editor, Peter Wilby, for allowing me to take several sabbaticals, and to Cristina Odone, Lisa Allardice, and Jill Chisholm for their support. In Italy, I was helped in various ways by Jennifer Storey, Domitilla Ruffo, Fabio Fassone, Claudia Ruffo, Ted Stanger, Catalina Manzanas, Jay Weissberg, and Frank Dabell. For her hospitality, my thanks to Contessa Orietta Floridi, whose inspirational restoration of the castle of Montecchio has ensured the survival of Hawkwoods most imposing residence.

Researching primary source material in the collections of the Archivio di Stato, the Italian State Archives, is often a baffling experience. For their advice and suggestions, I am indebted to the archivists and librarians of the Archivio in Lucca, Perugia, Cortona, Ravenna, Rome, Siena, Florence, and Cesena. My thanks also to the staff of the Archivio Storico Comunale of Bagnacavallo, the Biblioteca Comunale of Cotignola, the Istituto Storico Italiano per il Media Evo in Rome, and the Biblioteca Nazionale in Rome. In England, I was assisted by archivists at the Public Record Office and the Essex Record Office, and the librarians of the British Library and the London Library. For his help in researching and assembling the illustrations for the plate sections, I am grateful to Henry Volans at Faber and Faber.

Writers can develop antisocial ticks and general oddness: for their tolerant and kind response to this, unqualified thanks to Conrad Roeber, Anna Mike, Roger Thornham, Ann Pasternak-Slater, George Peck, Fiona Marques, Alexander Stonor Saunders, Julia Stonor, and Michael Wylde.

Finally, Carmen Callils support went far beyond the call of duty of any friendship. Without her bewildering faith in this book, it would not have been written.

In the third bay of the north aisle of the Duomo of Florence is Paolo Uccellos fresco portrait of John Hawkwood. Painted in terra verde against a dark red background, it is barely visible at first in the penumbra (Michelangelo criticised the dimness of these badly lit cathedrals as places where nuns could be raped and criminals could hide). The figure of Hawkwood emerges only slowly out of the brooding greyness. We see him on horseback, carrying his baton of command, riding towards the high altar, beneath the vortex of Brunelleschis impossible dome. Under the huge, spherical flanks of his white ambler, a simple Latin inscription reads: Ioannes Acutus Eques Britannicus Dux Aetatis Suae Cautissimus Et Rei Militaris Peritissimus Habitus Est This is John Hawkwood, British knight, esteemed the most cautious and expert general of his time.

The frescos dimensions twenty-five feet from top to bottom its imperial gravitas, and its position opposite the doors leading out of the cathedral into its history haunted square, and thence towards the civic centre of Florence, all speak unambiguously to the importance of its subject. There can be few more assertive sites than this in the narrative of the Renaissance, that great efflorescence of political and artistic expression which we continue to celebrate as a highpoint of civilised life. And yet Uccellos memorial constitutes a statement of extraordinary paradox: Hawkwood was indeed a knight, but he was also a ruthless mercenary, a notorious military journeyman whose activities shocked an age accustomed to atrocity, and earned him a reputation as the Son of Belial.

How did a man who was said to have inspired the proverb Inglese italianato un diavolo incarnato An Englishman Italianised is a devil incarnate come to be adopted and celebrated as a son of Florence, birthplace of the Renaissance? What had happened between his arrival in Italy in 1361 and his death in 1394 to erase the memory of his perfidious and most wicked deeds? Was Hawkwood not responsible for one of the most infamous massacres of his time, an episode worthy of a Senecan tragedy? Did he not manage the business of war so well that there was little peace in Italy in his day?

Ungrateful Florence! exclaimed Byron, for failing to provide a memorial to the all-Etruscan three of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. Florence, who denied Dante a resting place, erected a noble monument to a robber, complained the Victorian writer Ferdinand Gregorovius, who, pompous as his name, took the honour accorded to Hawkwood as a personal affront. But Gregorovius was surely right to question how an English mercenary was chosen above the Italian laureates to enter the pantheon of uomini illustri, great and famous men.

Hawkwoods story forces us to re-examine the true origins of the Renaissance, and the value systems on which it was based. It is a story that brings us uncomfortably close to a world without moral endings. Nothing is certain once this frontier has been crossed.