First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright David Murphy 2015

ISBN: 978 1 78159 292 2

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47387 293 6

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47387 292 9

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47387 291 2

The right of David Murphy to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Illustrations

Unless otherwise stated, images are from the authors collection.

List of Maps

Maps drawn by Dr Ronan Foley, Department of Geography, University of Maynooth

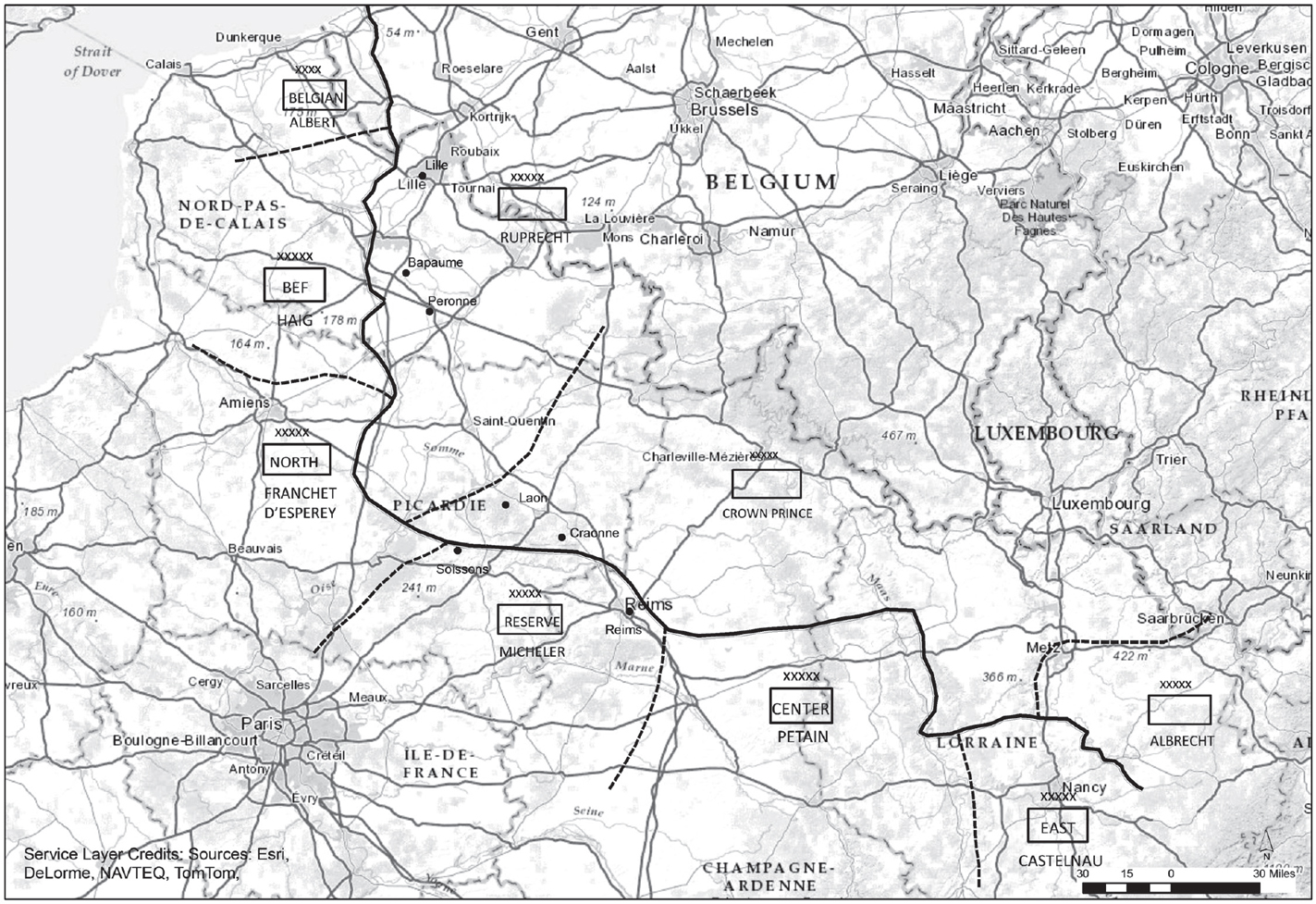

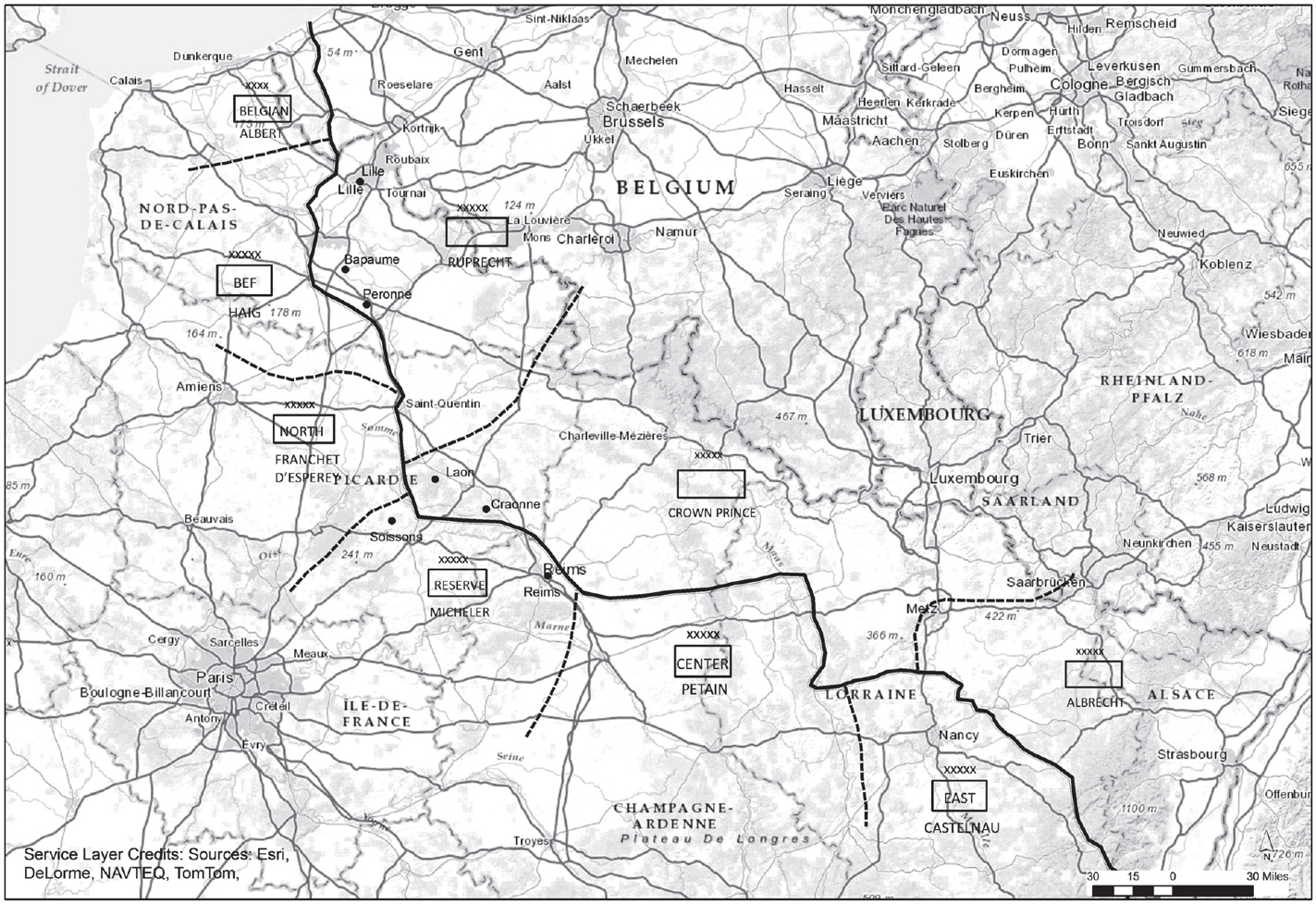

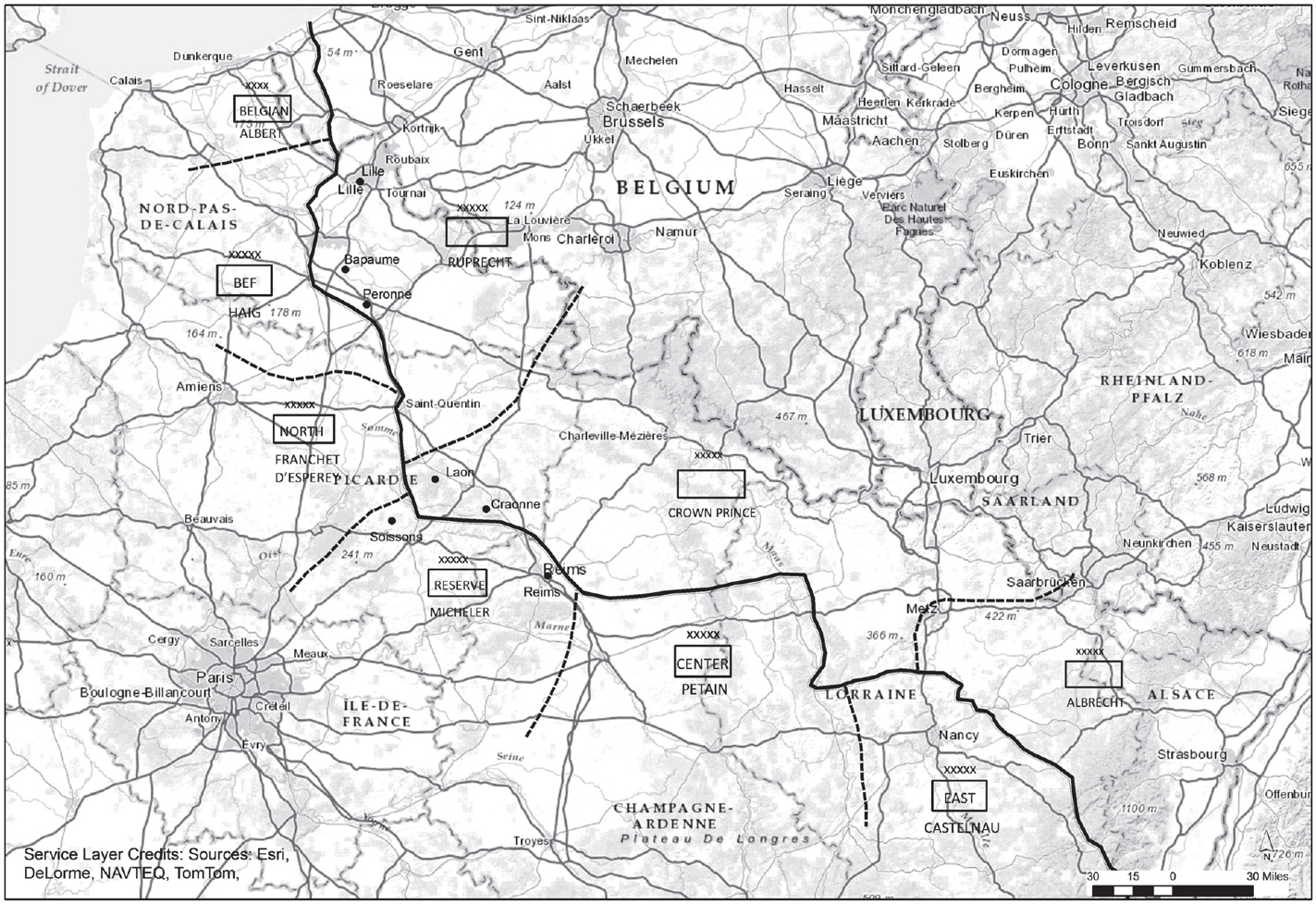

Map 1. The front line in February 1917.

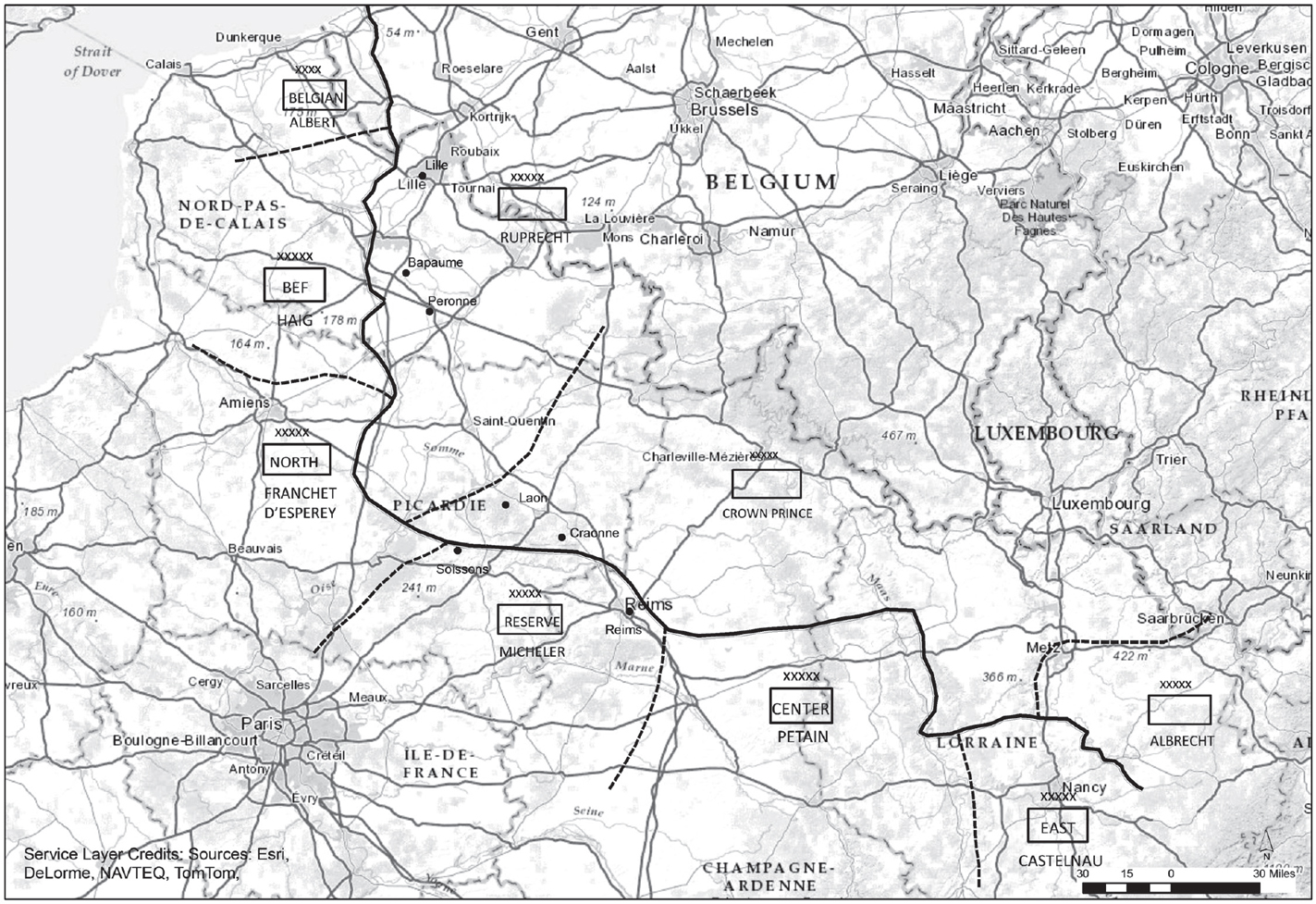

Map 2. The front line in April 1917 after the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line.

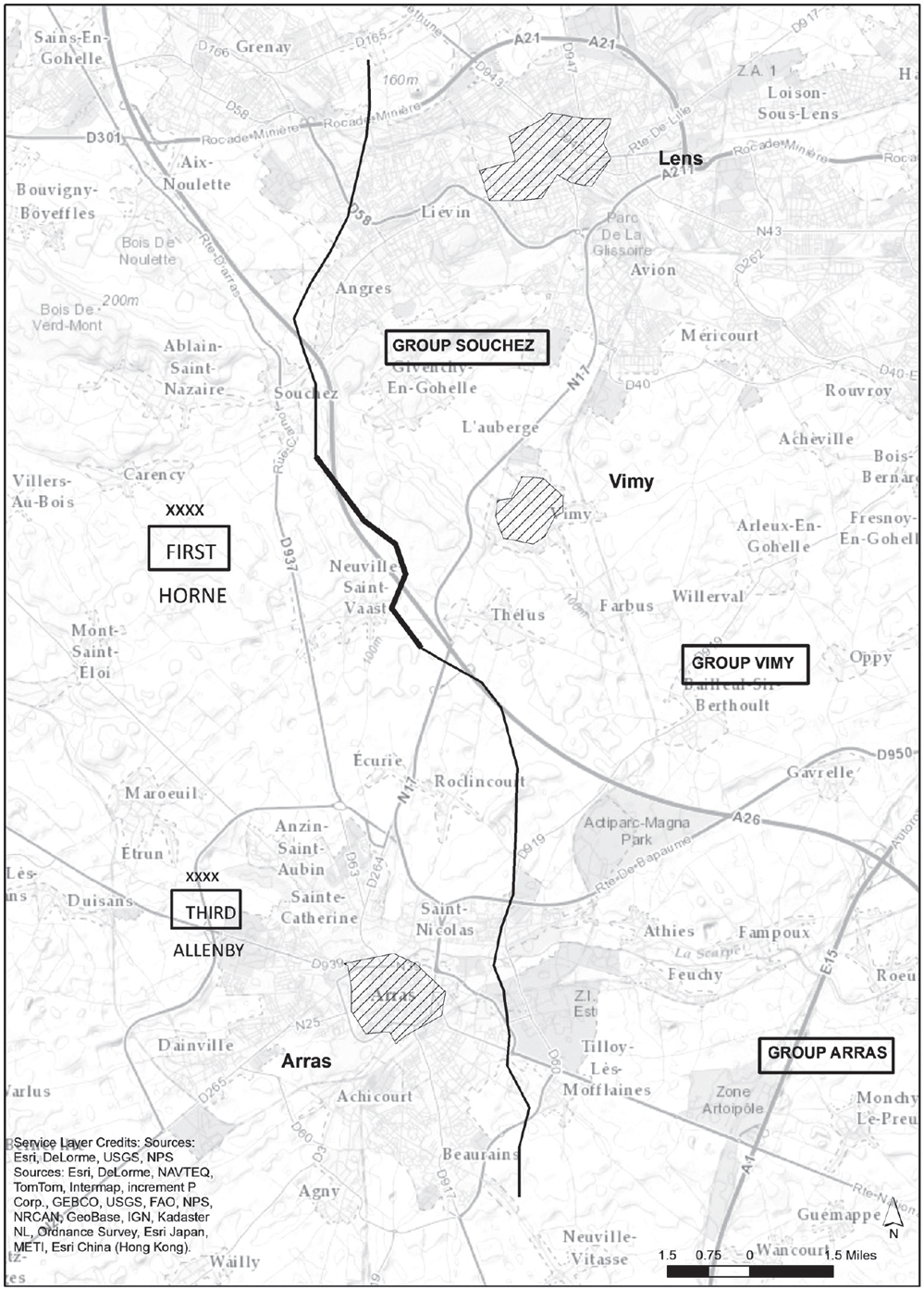

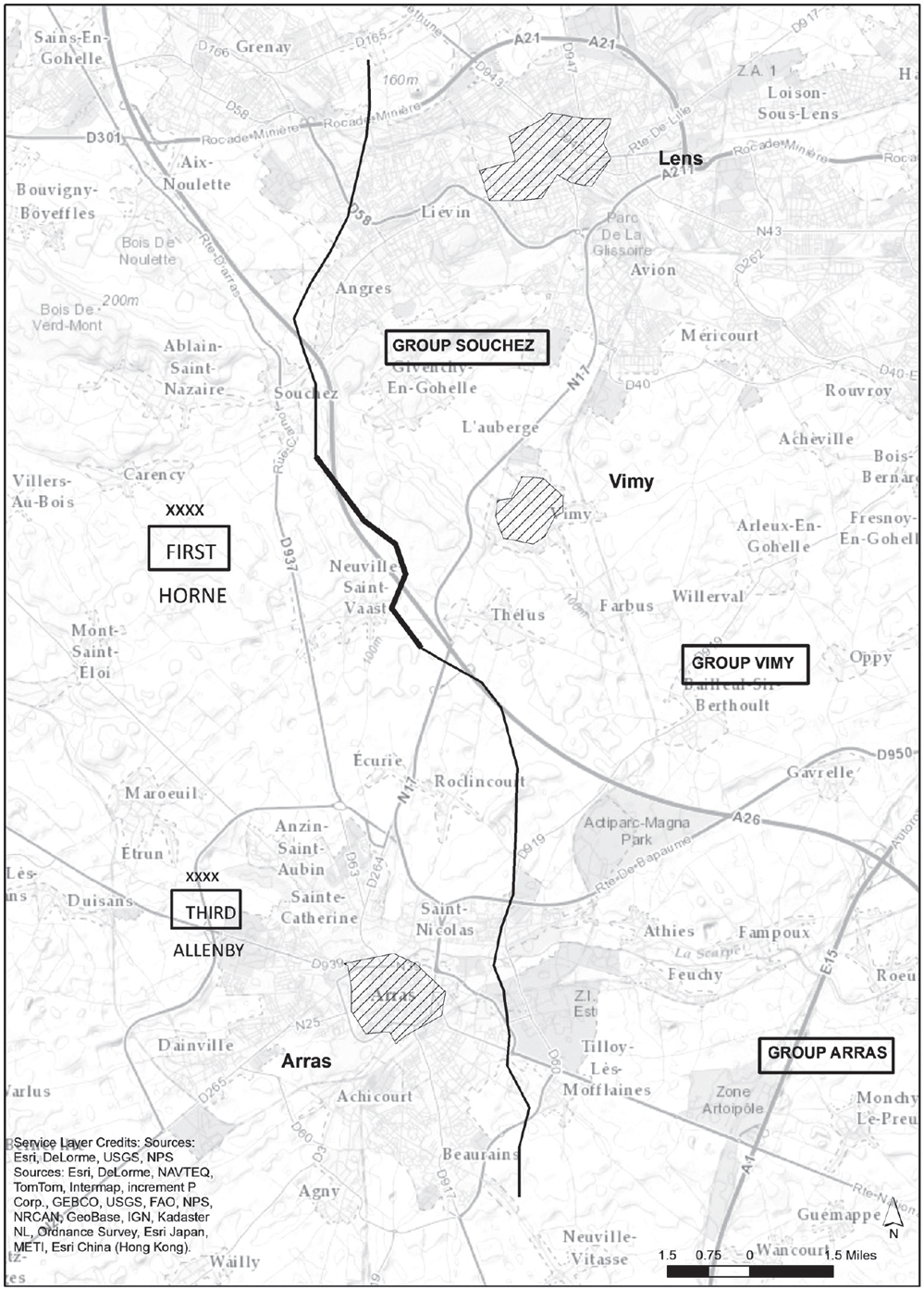

Map 3. The BEF area of operations at Arras and Vimy, April 1917.

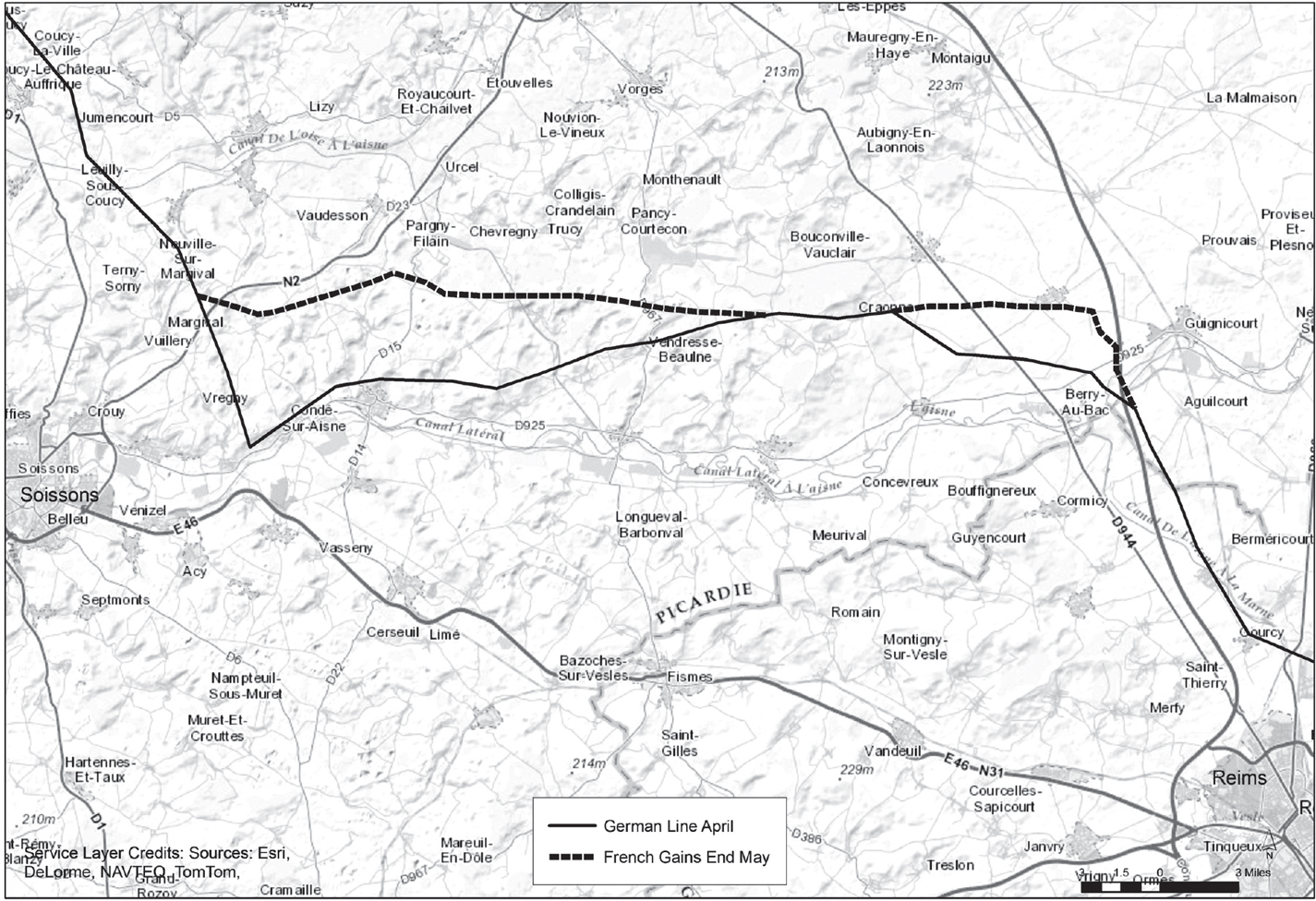

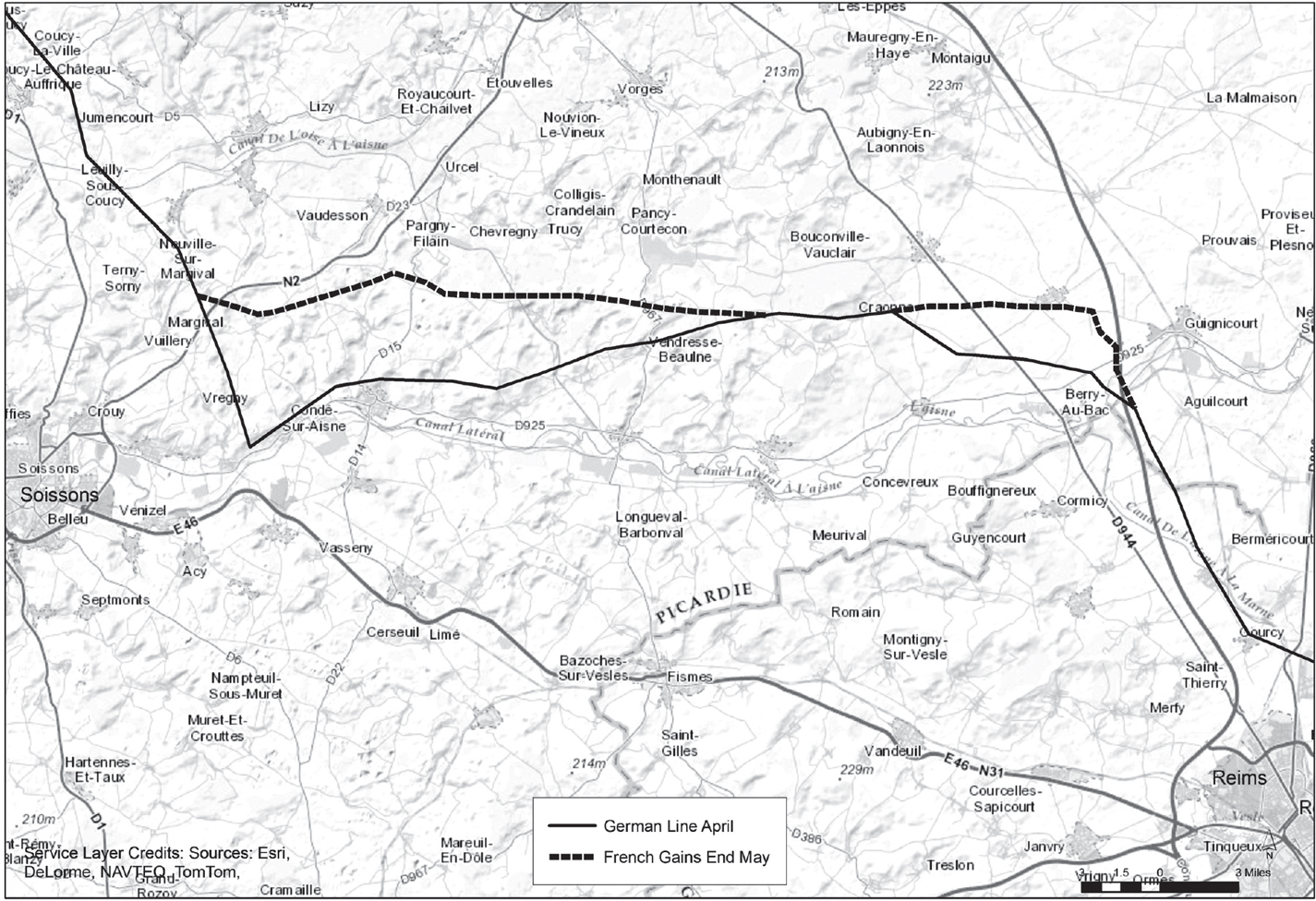

Map 4. French territorial gains by the end of the Nivelle Offensive in May 1917.

Abbreviations

AFGG | Les armes franaises dans la grande guerre (11 tomes, Paris, 192237) |

BEF | British Expeditionary Force |

C-in-C | Commander-in-Chief |

GAC | Groupe darmes du centre |

GAE | Groupe darmes de lest |

GAN | Groupe darmes du nord |

GAR | Groupe darmes de reserve |

GQG | Grand Quartier Gnral |

MEBU | Manschafts-Eisen-Beton Unterstand |

MG | Machine Gun |

SHD | Service Historique de la Dfense, Chteau de Vincennes |

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to many people for their help in completing this book. In France, my thanks go to the staff at the Service Historique de la Dfense in Vincennes. In particular, I would like to thank Colonel Rmy Porte and Dr Nathalie Genet-Rouffiac. I am extremely grateful to Christian Lapie for allowing me to reproduce a photograph of his sculpture Constellation de la Douleur on the Chemin des Dames. I would also like to thank the staff at the French Embassy in Dublin, including Salendre Maxence and Stephane Aymard.

In Ireland, I would like to thank my colleagues at the Department of History at Maynooth University, in particular Dr Ian Speller and Professor Marian Lyons. The assistance of Catherine Bergin, Peter Twomey and Dr Luke Diver was also much appreciated. The assistance of Dr Ronan Foley of the Department of Geography at Maynooth University in preparing the maps for this volume is gratefully acknowledged. I began this research some time ago while carrying out research in Paris for a project of Professor Ciaran Brady of Trinity College, Dublin, and I am grateful for that opportunity to work in French archives. I am also grateful for the input of Professor John Horne of TCD, Tom Burke of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association and Professor Gary Sheffield at the University of Wolverhampton. My thanks go also to Lar Joye of the National Museum of Ireland and Professor Harry Laver of South-Eastern Louisiana University. In the Irish Defence Forces, I would like to acknowledge the assistance and advice of Lt Col. Gareth Prendergast, Capt. Joe Gleeson and Capt. Alan Kearney. At Pen & Sword Publishing, my thanks go to Rupert Harding and Sarah Cook for their efforts in editing and preparing this volume for publication.

The assistance and advice of my sister Sharon was much appreciated. A special mention-in-dispatches to my wife Georgina, for her help and patience during this process.

Introduction

Nivelle had a plan. It was based on the combination of overwhelming artillery support and well-prepared infantry attacks which had served him so well at Verdun. And it would succeed in forty-eight hours, or it could be called off. No more Sommes, no more Verduns.

O n 14 July 1919 a grand victory parade took place in Paris. On the first Bastille Day since the end of the war, the people of France lined the Champs dElysees and the streets around the Arc de Triomphe. Parisians turned out in force while thousands travelled by train from around France to be present to mark the victory over the Central Powers and also to commemorate Frances great sacrifices in the war. Planning for the event was not without its problems. Tragically, the French air ace Jean Navarre was killed on 10 April while practising to fly through the Arc as part of the parade. In the final run-up to the parade, some territorial troops arrived in shabby uniforms and had to be hastily re-equipped at the last minute. During the night of 13/14 July a memorial cenotaph became stuck under the Arc itself and had to be freed by a unit of sweating army engineers. Also, members of the public invaded the seating reserved for dignitaries and had to be dislodged during the night by police, backed up by cavalry.

On 14 July the parade itself went ahead without any major hitch. A three-hour-long procession of troops passed through the Arc de Triomphe. They were led by a group of the war wounded and mutils in their wheelchairs, followed by Marshals Foch and Joffre, and Ptain leading army units; contingents from the other Allied nations also participated. The celebrations continued for the rest of the day with joyous crowds gathering in the squares and open areas of Paris.

There had also been some political unpleasantness before the event. Field Marshal Haig had to be persuaded to attend, while General Diaz, the senior Italian general, was not present. Question marks hung over some of the French generals and invitations were not certain. Marchal Joffre, for example, whose star had by now definitely faded, was initially not invited and when he finally was, questions arose as to where he should be in the parade. In general, however, even senior French officers whose wartime record was far from glorious were invited to attend.

One notable exception was General Robert Nivelle, who was commanding French forces in North Africa at the time. Nivelle was specifically excluded and instead supervised a parade in Algeria. For Nivelle, this course of events must have seemed hard to believe. Just a few short years previously, he had been commander-in-chief of the French field armies. During late 1916 and early 1917 he had enjoyed huge public acclaim and had been a darling of the press. For a period of some months he held sway in military matters and associated with the premiers of both France and Britain and senior political figures from both governments. Senior generals within his own army, his former superiors, were his subordinates. And in 1917 he had a plan to win the war. Now, as victory was being celebrated in Paris, he had been relegated to command of a military backwater, removed from the centre of military life and political power. In 1917 Nivelles career had been soaring like a meteor. Now he had crashed to earth. How had this come to pass?

Next page