Cover illustrations: Front: Viking-Age Coppergate. (Courtesy of York Archaeological Trust);

First published 2014

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Steven P. Ashby 2014

The right of Steven P. Ashby to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445601526 (PAPERBACK)

ISBN 9781445620589 (eBOOK)

Typeset in 10pt on 12pt Sabon.

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

No piece of research, however framed, is ever truly independent, and this book owes an immense debt to a large number of people. First, thanks are due to Dr James Barrett, who first kindled and supervised my interest in Viking-Age combs and combmaking. Professors Terry OConnor and Julian Richards once mentors, now also colleagues deserve an enormous amount of credit. The world of combs is small, but within this community, I have benefited from discussion with a number of researchers including but certainly not limited to Arthur MacGregor, Ian Riddler, Gitte Hansen, Andrea Smith, Colleen Batey, Martin Foreman, Andy Heald and Nicky Rogers. Thanks also to the numerous curators who have granted access to their collections; these include Kent Andersson (Statens Historiska Museet, Stockholm); Axel Christophersen (NTNU, Trondheim); Sten Tesch (Sigtuna); Bjorn Ambrosiani (Birka Project); Richard Hall and Christine McDonnell (York Archaeological Trust); Andrew Morrison (York Museums Trust); Thomas Cadbury (Lincoln Museums and Galleries); Rose Nicholson (North Lincs Museum); Anne Brundle and Lynda Aiano (Orkney Museum); David Clarke, Andy Heald and Martin Goldberg (Museum of Scotland); Tommy Watt (Shetland Museum); Gitte Hansen (Bergen Museum). I am grateful to Hayley Saul, Pat Walsh, Alyssa Scott, Nick Griffiths and Sven Schoeder for their illustrations, and to all who allowed me to use their photographs or reproduce their original drawings (particular thanks to Alison Leonard and Ross Docherty for their photography and canoe-steering skills). I am very grateful to the community of staff and students at the University of York, in particular Rob Collins, Emma Waterton, Leslie Johansen and Hayley Saul, all of whom have had to listen to my droning on about combs at one point or another; to Ben Elliot for discussion on the deerhuman relationship; and to Tania Dickinson and Mark Edmonds, who have variously encouraged me to develop different aspects of my work. Most of all, I should thank my family, and in particular my wife Aleks, who has had to bear the brunt of this, and Bill, the new arrival, whose keyboard-punching contributions have, unfortunately, had to be edited out. I should also thank Alex Bennett at Amberley for his editorial expertise and patience. Anything good about this book has emerged through discussion with the above named people. The rest is my fault.

It is a terrible shame that Anne Brundle never lived to see this book; I can only hope that she approves, and apologise that I didnt title it Comby Nations. This is for you, Anne.

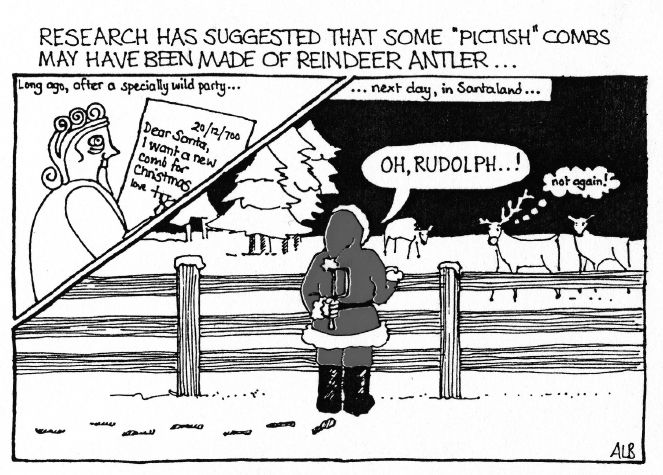

The truth behind Orkneys reindeer combs. (Cartoon by Anne Brundle)

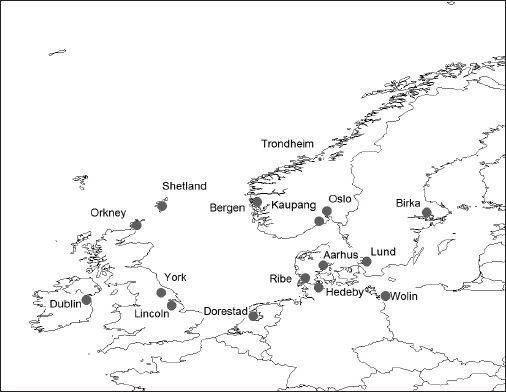

Localities mentioned in the text and other key sites of the Viking Age. (Drawn by Steve Ashby)

1

Introduction

Its market day, winter, AD 1000. A man is walking down Coppergate, a busy street in the northern town of Jorvik. He pushes through a crowd of people huddled together beside a small booth; someone inside is selling something, who knows what. He sidesteps children playing knucklebones in the street, as well as a dog that, fixated upon a stolen bone, is oblivious to his presence. He smells roasting meat, dried fish, rotting fruit. He hears the sound of traders hawking wooden cups and plates, woollen clothes, and jewellery: some pieces in amber, speaking of eastern shores, others of gilded metal, and of dubious provenance. He notes familiar faces and foreign costumes, local accents and alien dialects, the sounds of raucous laughter and bitter dispute. And then he reaches the stall hes been looking for.

The building consists of a small, low-standing wooden structure, with a thatched roof supported by rather insubstantial oak uprights, and overlying a timber-lined cellar. Just visible in the walls, cracks between timbers are packed with moss, and inside the building the walls are patchily lined with skins and rough textiles, while the floor is damp, uneven and strewn in places with debris of all kinds.From behind the building where a small animal pen and a number of foul-smelling pits are visible it is just possible to hear the sounds of chopping and sawing. Spread out on the ground in front of the property is a wickerwork mat, and on this lie all manner of objects: pins, needles, ice skates, fittings for belts and swords, and strange objects that must be something to do with textile manufacture, all with the subtle lustre of freshly worked bone. Most striking of all are a familiar collection of objects notable at first for the lack of polish that gives them away as being made of deer antler, rather than bone. For all their duller finish, their appearance is nonetheless arresting. There are a range of forms, some long, some short, some that perfectly preserve the graceful curve of the antler from which they were cut, others much shorter and more regular, as if closely following a well-understood template. Some have handles, others do not, and there is a wide range of ornament, from the familiar ring and dot design that has been common to personal objects for generations past, to the carefully spaced arrangements of chevrons that must represent a new fashion, perhaps from overseas. Each object consists of many small, strangely shaped pieces of antler, carefully riveted together to form a recognisable whole. Most impressive of all are the arrays of teeth along the long axes of the objects: perfectly straight, even, tapered to a gentle point, and so fine that five teeth occupy a space only about the width of a fingertip.

These objects are, of course, hair combs, and they are the chief reason for our protagonists venturing out to market today. After he has spent a few moments inspecting the objects, and identified a comb that seems appropriate, the noise from the rear of the workshop ceases, and the artisan comes forward to greet his customer. This combmaker seems familiar. Was he here last year? Certainly it will be worth remembering him, as he can make a good comb, and this seems like a relationship worth cultivating. After asking his name, engaging in some friendly small talk and not a little haggling, an agreement is reached and the trade is completed.

![Haywood - Viking: The Norse Warrior’s [Unofficial] Manual](/uploads/posts/book/98981/thumbs/haywood-viking-the-norse-warrior-s.jpg)