WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 1968

Winvian Farm, Litchfield, Connecticut

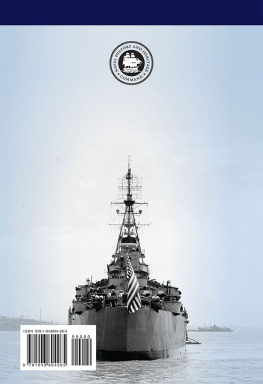

On a windswept fall day, on a gray morning after the colorful agony of autumn had passed but before the deep, blank snows of winter sealed off the world, Captain Charles Butler McVay III, the former commander of the World War II cruiser USS Indianapolis, woke and took stock of his day. He was alone in a drafty bedroom of a colonial house called Winvian Farm, outside Litchfield, Connecticut, adrift in rich horse country. His window looked out at a flagstone terrace built for grand cocktail parties and at a swimming pool; beyond that, he could glimpse the scattered homes of bankers and lawyers whose offices were in New York, 100 miles to the south. The surrounding woods, black and skeletal in the morning light, scratched at a gray sky.

There was much to do. Earlier in the week, the captain had drained the pool for the winter, and this morning he would finish the ritual of closure by putting up snow fences and wrapping the propertys hedges with burlap. After lunch, he often played bridge; later in the afternoon, he might putter in his woodshop or go duck hunting on Bantam Lake. The captain was seventy years old, in fine health, with white hair and black eyebrows that framed piercing, but gentle, blue eyes. Always dapper, always self-assured, he dressed in crisply pressed khaki shirt and pants and leather slippers, clothes that had become a uniform for him, a vestige of his life in the wartime navy.

Vivian!

His wifes room was across from his own spartan billet, which included just a twin bed and a night table with a Bible that he read every night before turning in at ten. In theroom was a desk drawer filled with letters from the families of sailors hed commanded, bound up in string and rubber bands. The letters troubled the captain; they had always troubled him. Each Christmas even more arrived, and December 25 was fast approaching.

There was no answer from Vivians room, which wasnt surprising. Vivian was his third wife. Vivacious, beautiful, and tempestuous, she was in the habit of sleeping late. A former fashion model, she sat at the center of the social whirl of Litchfield; by all appearances, she and Charlieas all his friends called himmade a wonderful pair, a handsome couple. The social events often bored McVay, who could be shy and even recalcitrant, at times preferring the solitude of the duck blind to the patter of a cocktail party.

He made his way down the creaking staircase to the kitchen, where, lately, hed been spending more and more time talking with the housekeeper, Florence Regosia, a kind-hearted young woman whod worked for him for eight years and who insisted on calling him Admiral. Hed actually been promoted to the rank of rear admiral, his official naval title upon his retirement, whats called a tombstone promotion. Such promotions, though, are a bit like being named captain of the football team and then sitting out the game. McVay himself usually insisted on Captain; it seemed more honest to him.

After exchanging pleasantries with Florence, he took his black Lab, Chance, for a walk in the woods behind the house. Afterward, he met Al Dudley, his gardener and handyman, and they began work on the shrubs in the front yard, binding them mummy-tight with twine and burlap for the long voyage into winter.

From the yard of Winvian Farm, you can look out at the country road leading north into Litchfield, and south toward the main arteries leading to the sea. Theres a stone fence, a bank of apple trees, and beyond that some woods and fields galloping into the distance. Many of the houses in Litchfieldwere built by nineteenth-century sea captains, and many of them still sport widows walks. Its a hilly landscape, and the village is sunk in a wooded valley, off a main thoroughfare, as if the wives of these captains had wanted to drag them as far inland as possible, away from the sea, out of dangers way. Its a place people usually come to in peace and prosperity at the end of life; its a place to come to and forget things. The captain had lived here for nearly seven years.

A barn and machine shed and the cold whisper of the November wind surrounded McVay and his gardener. They worked well together, side by side, McVay chatting, pliers and twine in hand, as if nothing at all was bothering him.

But something was.

After a couple of hours, they broke for lunch, and Al Dudley returned to his own smaller house across the county road. Inside the Winvian farmhouse, Florence was setting out luncha sandwichon the dining room table. Vivian was off somewhere in another room, eating alone. Before sitting down, the captain went upstairs to his bedroom, ostensibly to change into something suitable for an afternoon of playing bridge at the Sanctum, a gentlemans club situated on the trim town green in Litchfield. He closed the door.

Beyond the bedroom windows, the wind was stripping what leaves were left on the trees, and a freezing rain was worming its way under the eaves, looking for a way in.

On the night table sat a holster, and in the holster was a navy-issue .38, a revolver, which the captain picked up.

A knock came at the door.

Admiral, your lunch is ready. It was Florence.

Ill be down in a minute.

For all the captains customary good cheer, Florence had been worried about him. She knew he was having nightmares; hed told her they were filled with circling sharks. When shed reminded him, several weeks earlier, that the storm windows also needed installing, he had remarked,Oh, that wont be necessary.

Why not?

Because, the captain told her, I wont be here.

Now, Florence returned downstairs, and soon the captain appeared in the doorway, a blank look on his face. He was still dressed in his khaki.

Admiral, Florence said, you have to go play cards today.

Oh, yes, said McVay. I know.

When Florence asked if hed like some lunch, he replied, Ill eat it later.

Florence eyed him, and then she returned to the kitchen.

The captain pushed open the front door and stepped through a small wooden entryway erected in anticipation of the coming winter snow. He lay down on the stone walk with his head resting on the marble step, his gaunt face tilted up at a gray sky.

Beside him, as he lay alone in the front yard, stood Chance, who watched, head cocked to one side, as the captain brought the cold barrel of the gun to his head.

In McVays left hand was a set of house keys, and on the key ring, a metal toy sailor, a worn memento from happier times. Hed carried it with him around the world, across several oceans, and into battle. Hed been given the toy sailor as a gift when he was a boy.

Whatever good fortune the captain had enjoyed in his life, it had run out. He pulled the trigger.