ABOUT THE AUTHOR

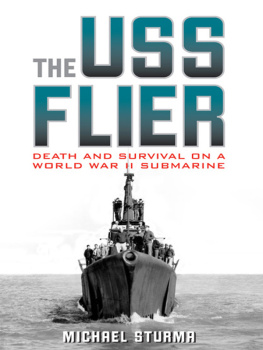

Douglas A. Campbell is the author of The Seas Bitter Harvest: Thirteen Deadly Days on the North Atlantic. He worked as a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer for twenty-five years. He also writes for Soundings magazine. He has covered topics ranging from the American economy to Atlantic eels, and has had a lifelong interest in the sea. For this book, he interviewed survivors of the sinking of the Flier and visited the Philippines location where the sailors washed ashore. Campbell lives near Philadelphia in Beverly, New Jersey.

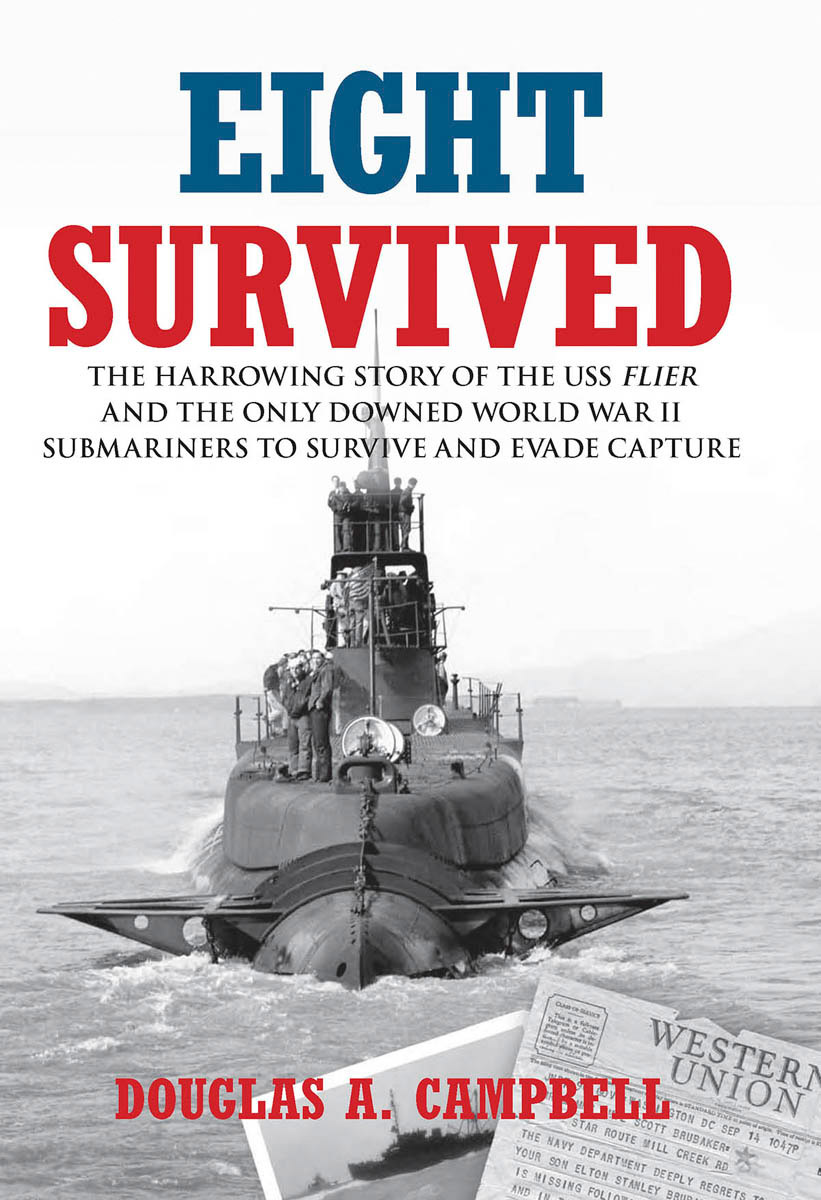

EIGHT SURVIVED

Also by Douglas A. Campbell

The Seas Bitter Harvest

Copyright 2010 by Douglas A. Campbell

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Text design by Maggie Peterson

Maps by Maryann Dube, Morris Book Publishing, LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Campbell, Douglas A.

Eight survived : the harrowing story of the USS Flier and the only downed World War II submariners to survive and evade capture / Douglas A. Campbell.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59921-934-9

1. Flier (Submarine) 2. World War, 1939-1945Naval operationsSubmarine. 3. World War, 1939-1945Naval operations, American. 4. World War, 1939-1945Search and rescue operations. 5. SubmarinersUnited StatesBiography. 6. Disaster victimsSulu SeaBiography. 7. Submarine minesSulu SeaHistory20th century. 8. ShipwrecksSulu SeaHistory20th century. 9. Survival after airplane accidents, shipwrecks, etc.Sulu SeaHistory20th century. 10. Sulu SeaHistory, Naval20th century. I. Title.

D783.5.F56C36 2010

940.5451--dc22

2010026655

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CHAPTER 1 TREACHEROUS PASSAGE

The sea was in a furious mood. Piled on its surface were great, gray waves, living monsters who could humble even the greatest warships. Yet, the USS Flier was but a submarine, at about 300 feet, one of the smaller vessels in the navy. Even when submerged, it pitched and rolled like a slender twig. But inside Flier were no ordinary sailors. They were submariners: menmost of them quite youngselected from the ranks for their virtues of fearlessness and its companion trait, optimism. Their mood was bright. Despite the beastly roar and hiss of the Sea above them, none believed that on this day his death was at hand.

The reaper might come later, when their boat reached the actual battle lines in this, the third year of World War II. And probably not then, either, they thought. The momentum of the conflict had turned in their favor. There was a sense, pervasive on board, that destiny was with the Allies. Everyone expected to be around for the final victory. These were young menmany of them greenled by a handful of sailors creased by the experience of having survived at sea. Death was for someone else, the enemy, even on January 16, 1944, even on the Pacific Ocean, the greatest naval battleground in history, a place where tens of thousands of Americans had already died.

But the men aboard the Flier could not ignore the thrashing as she bucked and twisted. For the one young cowboy in the crew, it had to make him think rodeo bull. He and his mates joked uneasily about the sobriety of the welders who had built the submarine back in Groton, Connecticut.

They had left Long Island Sound in the brand-new boat on November 23, 1943, after several successful Sea trials there. The smell of fresh paint still competed with the ever-present stink of diesel fuel as they steamed south and then passed through the Panama Canal. The crew enjoyed the stop in Hawaii, basking in the warmth of the island winter days before resuming their westward journey toward the naval hot spots of the Pacific.

Now in these angry seas they approached the atoll known as Midway, one of the navys refueling depots. Once beyond Midway, their first wartime patrol aboard Flier would begin, and their recorddistinguished or dreadfulwould be tallied in tons of enemy shipping sunk. With young hearts and a sense of invincibility, they knew that the slamming of their submarine by the Sea was only a tune-up for the coming combat. And they had no fear.

Because it was daytime, Flier was running deep, avoiding the worst that the ocean was offering, drawing electricity from its huge banks of storage batteries to run its motors. The night before, when the storm was no less fierce, they had surfaced to run the diesel engines that charged the batteries. Then, the whole fury of a winter storm, with winds topping forty knots, was sweeping the Sea, plowing up huge, heaving waves in endless ranks across the submarines path. Now, even beneath the surface, the seventy-eight sailors aboard Flier felt the surge from the storm-driven seas that had raced thousands of miles unimpeded by land. But they knew that soon, they would get a break. The shelter of Midway was only hours away. Midway, where the Allies had won their first decisive battle of the war. Midway, a symbol of Allied destiny.

Just after noon, Commander John Crowley heard his radar operator in the conning tower report contact with land. The blip on the radar screen showed a small speck about fifteen miles away. Through his periscope, the skipper saw that while the seas were still running high, the storm above had easedwinds were force four, about fifteen miles per hourand occasional rain squalls came from the mostly overcast sky. Once in a while, a hole in the clouds let sunlight through, enough so that Fliers navigator could get a sun sight with his sextant.

Crowley, relying on the radar report of land, gave the order to steer due west, and by 1:15 p.m. he saw through his periscope the low group of islands that are the Midway atoll, about nine miles away. At two oclock, Flier was two miles south of the entrance to Midways channel and was sitting on the surface, with Crowley on the bridge, feeling the breeze on his left cheek. A detail of sailors was stationed on the rear deck, prepared to help in the anchoring of the submarine when it reached the dock. Fifteen minutes later, Fliers semaphore light flashed a signal to a tower on one of Midways islands and got a reply: stand by for pilot.

With the seas running high, it would be essential for a harbor pilot to steer Flier through the inlet. Even in calm weather, the naval base would dispatch a pilot, so hazardous were the coral reefs that surrounded the little port. Crowley, who had been at Sea most of the thirteen years since he had graduated from the Naval Academy, was no novice sailor. He had served as a junior officer on two submarines and then had commanded the submarine S-28 before taking charge of Flier. He had read the charts and the descriptions of Midways channel, but he had never entered this port. Nautical charts are helpful, and a practiced eye can learn a lot from them. They show obstructions, depths, the placement of buoys that can be used to help navigate. But close to land, the seas are tricky. There are crosscurrents and the local effects of wind to be considered, and nothing helps navigate such waters more than local knowledge. So Crowley was relieved when the message came out from the tower on sand Island, the larger of Midways two big islands, that the pilot was on his way.