The Tragic Fate of the

U.S.S. Indianapolis

The Tragic Fate of the

U.S.S. Indianapolis

The U.S. Navys Worst Disaster at Sea

Raymond B. Lech

All the names in this book are real, with one exception.

First Cooper Square Press edition 2001

This Cooper Square Press paperback edition of The Tragic Fate of the U.S.S. Indianapolis is an unabridged republication of the edition first published under the title All the Drowned Sailors in New York in 1982.

Copyright 1982 by Raymond B. Lech

Designed by Louis A. Ditizio

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

Published by Cooper Square Press

An Imprint of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group

150 Fifth Avenue, Suite 911

New York, New York 10011

Distributed by National Book Network

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lech, Raymond B., 1940

The tragic fate of the U.S.S. Indianapolis : the U.S. Navys worst disaster at sea / Raymond B. Lech. 1st Cooper Square Press ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: All the drowned sailors. New York : Stein and Day, 1982.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8154-1120-8

1. Indianapolis (Cruiser) 2. World War, 1939-1945Naval operations, American. I. Title.

D774.I5 L43 2000

940.54'5973dc21

00-064490

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

To my Captain: Bernadette

To my Crew: Barbara and Christopher

and

To the surviving survivors of the

U.S.S. Indianapolis

Contents

List of Illustrations

Illustrations following

Maps

1. The U.S.S. Indianapolis has been lost in the Philippine Sea as the result of enemy action.

2. The next of kin of casualties have been notified.

NAVY DEPARTMENT COMMUNIQUE

NO. 622, AUGUST 14, 1945

Responsibility extends from the Commander in Chief, Pacific, to the Lieutenant Operations Officer, Tacloban, and into the Bureaus of the Navy Department.

MEMO FROM NAVAL INSPECTOR

GENERAL TO THE CHIEF OF

NAVAL OPERATIONS.

JANUARY 7, 1946

The Tragic Fate of the

U.S.S. Indianapolis

1.

Mission

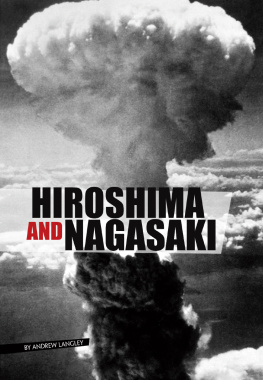

DURING the summer of 1945, the Pacific island of Tinian was the largest air base in the world. Isolated from the normal hustle of the field sat a silver B-29, poised for one fateful mission. The carefully trained crew of Enola Gay was eager to make the drop that, it was hoped, would end the four-year war with Japan. But first, the weapon had to be delivered from the middle of an American desert.

A quarter of a world away, the heavily armed convoy rolled from Los Alamos to an Albuquerque airfield where a trio of lumbering DC-3s anxiously awaited their precious cargo. Loaded down with technicians, security people, and The Bomb, the planes fought their way into the southwestern sky and eventually arrived at Hamilton Field.

Now that the key components of the weapon were in the heart of California, the obvious question was, How do we get them to the island? By air or by sea?

The air route was the most desirable since it would eliminate the time problem, but the scientists who had painstakingly developed this awesome weapon werent sure what it would take to set it off. They knew theoretically it should work, but the arming and detonation of this atomic power had not yet been tested (and wouldnt be for another few weeks). If, by chance, the plane crashed during takeoff, it was soberly terrifying (and conceivable) to the people at Los Alamos that the city of San Francisco just might be blown off the map of the United States.

Fourteen miles to the east of Hamilton Field and just twenty-five miles northeast of the famous San Francisco Opera House was the Mare Island Naval Shipyard. Sitting there for over two months was a war-weary heavy cruiser, repairs just completed from a devastating kamikaze attack off Okinawa. It was decided by Major General Leslie Groves (Manhattan Project) and Rear Admiral William Purnell that this sixteen-year-old ship would be their transport and that she would sail westward to rendezvous with Enola Gay.

The captain was hurriedly called into the office of Admiral Purnell in San Francisco. Also present was Navy captain William Parsons, who was to assemble the bomb on Enola Gay while she was flying toward Hiroshima. The skipper of the heavy cruiser listened intently to his very simple orders, which were to deliver a particular cargo, as fast as possible, to Tinian. He was also told that this freight was to be guarded with his life and the life of his ship, and that if they were sunk en route and there was only one lifeboat left, the cargo was to be put on that boat. Furthermore, neither he nor his crew had a need to know what the cargo was. Bewildered, the officer left.

The death warrant of his ship, of 880 men, and, finally, himself, had been signed.

On July 15, 1945, the U.S.S. Indianapolis, former flagship of the Pacific Fifth Fleet, dropped her heavy anchor in San Francisco Bay off Hunters Point Naval Shipyard. Around noon on this Sunday, The Bomb was brought aboard. (Actually, it was only the internal components of the weapon that were being shipped and not the outside casing, which was already on Tinian.) A metal cylinder or lead bucket, weighing about two-hundred pounds and containing the deadly uranium, was carried aboard, securely strapped to the deck up in Captains Country, and guarded by Army officers from Los Alamos. At the same time, a fifteen-foot heavy wooden crate holding the detonating mechanism, or cannon, was lashed to the deck in one of the ships hangars and protected by members of the Marine detachment. Except for the vigilant sentinels, no one dared go near the bucket or the cannon.

At 5:30 A.M. the next morning (Monday, July 16, 1945), an enormous blast, coupled with a blinding flash, rolled its way across the New Mexico desert, while a poisonous mushroom reached into the early morning sky. As if set off by a nuclear starters pistol, at 8:00 A.M., the Indianapolis hoisted anchor and a half hour later, all 9,950 tons of her slipped between the narrow confines of the bay and passed beneath the Golden Gate. Of the entire crew aboard her at that moment, 73 percent would be dead in two weeks. Fate had destined that this vessel would go down in the record books as the greatest disaster of a ship at sea in the history of the United States Navy.

On this very same day, while the Indianapolis was breaking out into open water, Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto ordered the lines cast off and, with the music of a band echoing in the background, the Imperial Japanese submarine 1-58 gently slipped away from her pier at Kure. In exactly fourteen days, this 2,600 ton underwater weapon and her 105-man crew would annihilate the heavy cruiser Indianapolis.

Captain Charles Butler McVay, III, son of the former Commander in Chief of the United States Asiatic Fleet, was slated for the top of the Navy ladder. Appointed to Annapolis by President Wilson, he graduated in 1919 and in the ensuing years ran the normal gauntlet of posts required of up-and-coming officers. He served on various types of vessels from tankers to battleships, did his stint at the Navy Department in Washington and as Naval aide in the Philippines. Prior to taking command of the

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.