JADOOWALLAHS,

JUGGLERS AND JINNS

A Magical History of India

John Zubrzycki

PICADOR INDIA

To my children, Adele, Alexander,

Jonathon and Nicolas

Of the jugglers alone, a whole book might be written

James Inglis, Tent Life in Tigerland, p.234

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

SO WONDERFULLY STRANGE

D ILSHAD Garden, on the eastern outskirts of New Delhi, is an unlikely location to be probing the veracity of a four-century-old account of Indian magic. To use the appellation Garden was a town planners clever sleight of hand. There are few open spaces in this congested warren of low-rise seventies-style government housing. The grit and fumes of the Grand Trunk Road make it even harder to imagine how northern India might have looked in the Mughal period. My destination was a small park surrounded on three sides by ochre-coloured flats. My guide was the infectiously enthusiastic Raj Kumar, General Secretary of the Society of Indian Magicians, winner of the International Merlin Award, master of the Rope Trick and levitation act, team leader at the Delhi School of Magic, and founder of MAZMA, the Society for Uplifting Traditional Magic & Performing Arts. It was late November, the middle of the marriage season the busiest period of Delhis always-hectic social calendar. Raj Kumar was negotiating the maze of traffic, while fielding bookings for magic shows on his super-sized smartphone. Talent scout and teacher, he had dozens of semi-pro mystifiers on his books, ready to dazzle guests at weddings, corporate gigs and birthday parties.

Waiting at the park were a dozen-or-so jadoowallahs, traditional street magicians, who had come from Ghaziabad, just across the Uttar Pradesh border. Raj Kumar proudly told me how he had pulled them out of poverty by buying each a motorbike. Without their own transport, getting to the small towns and villages where they can still perform is difficult. Making a living as a street magician in New Delhi is tough. Begging is officially banned in the Indian capital and under the law, street magicians are lumped together with beggars and other vagrants, making them easy targets for the bribe-taking police. But this was very much Raj Kumars territory and over the next two hours his rag-tag magical assemblage performed unmolested, presenting a repertoire of tricks that bore a striking similarity to what the Mughal emperor Jahangir had witnessed in the early seventeenth century.

Jahangir presided over an empire at the height of its power and decadence. He never went near a battlefield and rarely drew a sword, though in his memoirs he admits to ordering one of his grooms to be killed on the spot and two palanquin bearers hamstrung and paraded around his camp on a donkey, for disturbing a nilgai during a hunting trip. The peace and stability his father, Akbar, had left behind allowed Jahangir to indulge in shikari, sensual pursuits, poetry and drinking the latter being an addiction he spoke of with pride:

Encompassed as I was with youthful associates of congenial minds, breathing the air of a delicious climate ranging through lofty and splendid saloons, every part of which decorated with all the graces of painting and sculpture, and the floors bespread with the richest carpets of silk and gold, would it not have been a species of folly to have rejected the aid of an exhilarating cordial and what cordial can surpass

He was also fascinated by magic once halting his convoy to watch the performance of a Carnatic juggler who could swallow a chain three yards long. His obsession with necromancy interfered with the day-to-day running of the court to such an extent that a group of complainants wishing to report abuses of power by the Governor of Bengal, had to dress up as magicians to get his attention.

Midway through his memoirs, as he contemplates a life well lived, a life of gold, and jewels, and sumptuous wardrobes, and in the choicest beauties Over the course of what would have been several days and nights, they effected no fewer than twenty-eight tricks, a compendium of marvels that encompassed many of the legendary feats of Indian magic all executed with such skill and consisting of such marvels, that the loquacious Mughal would often be lost for words.

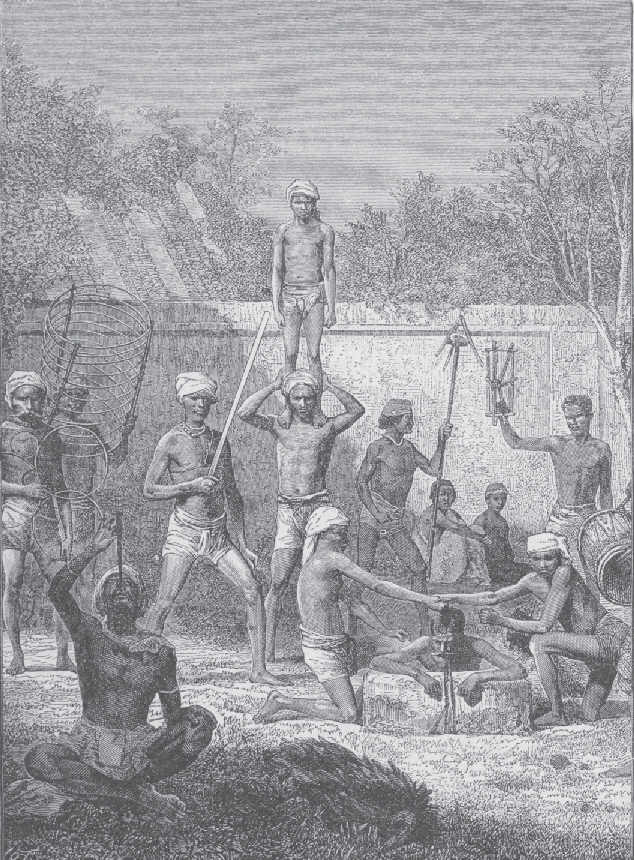

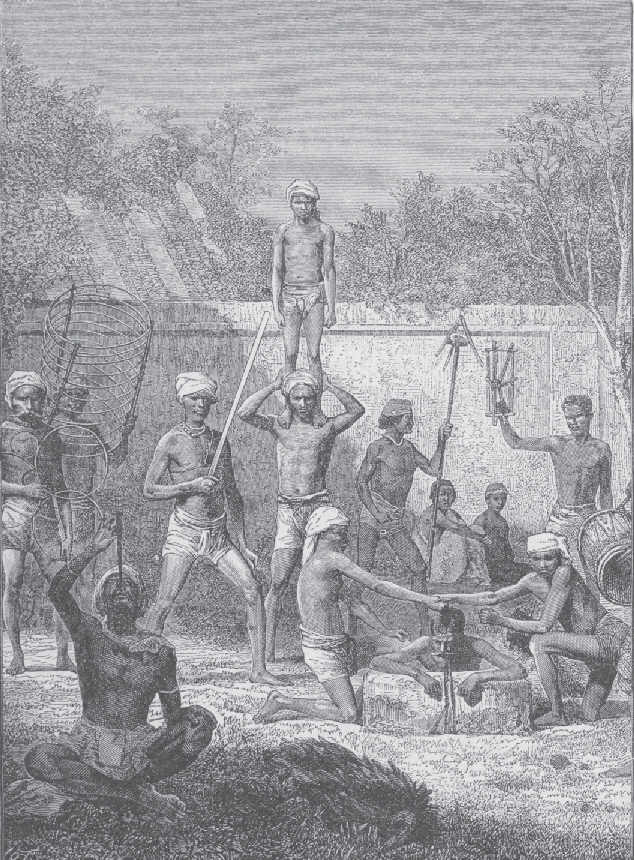

Group of Indian jugglers from Zigzag Journeys in India, 1887. Library of Congress.

The chief juggler began by promising to produce any tree in an instance, merely by placing a seed in the earth. Khaun-e-Jahaun, one of Jahangirs nobles, ordered a mulberry tree. The

That evening, one of the jugglers came before Jahangir and spun in a circle, clothed in nothing but a sheet. From beneath it he took a magnificent mirror that produced a light so powerful it illuminated the hemisphere to an incredible distance round. Travellers would later report that on that very same night, at a distance of ten days journey, the sky was so floodlit it exceeded the brightness of the brightest day

From an empty bag emerged two cocks that fought with such force and fury, that their wings emitted sparks of fire at every stroke. Two partridges of the most beautiful and brilliant plumage appeared, followed by two frightful black snakes that attacked each other until they were too exhausted to fight any longer. When a sheet was thrown over the bag and lifted off, there was no trace of the snakes, the partridges or the cocks. A marvellous birdcage revealed a different pair of birds as it revolved, a carpet changed colours and patterns each time it was turned over, and an otherwise empty sack produced a seemingly endless variety of fruits and vegetables. Standing before the Mughal emperor, a man opened his mouth to reveal a snakes head. Another of the jugglers pulled the serpent out and in the same manner, produced another seven, each of which was several feet in length. They were thrown on the ground where they were seen writhing in the folds of each other, and tearing one another with the greatest apparent fury: A spectacle not less strange than frightful. Also wondrous was a ring that changed its precious stone as it moved from finger to finger. The magicians then showed a book of the purest white paper devoid of writing or drawing. It was opened again to reveal a bright red page sprinkled with gold. Then appeared a leaf of beautiful azure, flecked with gold and delineated with the figures of men and women. Another

But these were mere tricks compared with two feats that went far beyond the ordinary scope of human exertion, such as frequently to baffle the utmost subtlety

It was the Rope Trick, the twenty-third of the Bengali jugglers legerdemain display, that was the most marvellous of all and would become the benchmark against which all feats of Indian magic would be measured.

They produced a chain of fifty cubits in length, and in my presence, threw one end of it towards the sky, where it remained as if fastened to something in the air. A dog was then brought forward, and being placed at the lower end of the chain, immediately ran up, and reaching the other end, immediately disappeared in the air. In the same manner a hog, a panther, a lion, and a tiger, were alternately sent up the chain, and all equally disappeared at the upper end of the chain. At last they took down the chain and put it into a bag, no one even discovering in what

Though he had seen magic at his fathers court, Jahangir was forced to admit that never did I see or hear of anything in execution so wonderfully strange, as was exhibited with apparent facility by these seven jugglers. He dismissed the troupe with a donation of fifty thousand rupees and ordered each of his amirs to give upwards of one thousand rupees in appreciation of their performance.

Next page