Contents

Introduction

I t is an autumn evening, the evening of October 31, to be precise. A biting wind churns the clouds and tears the last leaves from the trees to send them spinning every which way over the damp ground, rich with the fragrances of autumn. It is the end of the day, the beginning of the night, that twilight period when light and shadow commingle and it is difficult to determine where one ends and the other starts. In appearance it is a simple autumn evening, like any other. However, in the villages and cities as well as in the remote rural regions lost in the valleys, there is something else going on, something out of the ordinary.

It can be seen first in the behavior of the men and women leaving work. They appear relaxed, if not happy. They linger willingly in the bars, or, if they have returned straight home, they have done so knowing that tomorrow they will have broken the infernal cycle of work for a day. Ah! It is true. The next day is a holiday, what was formerly called, under the Ancien Rgime, a church solemnity, or a religious festival, which even the very secular French Republic has preserved in the official calendar, to the satisfaction of all its citizens, both believers and nonbelievers.

It is, in fact, All Saints Day. However, in the minds of most people it is a sad day. Families make visits to the cemetery to leave chrysanthemums on the tombs of the dearly departed. This ritual gesture of commemoration of the deceased is usually accompanied by a kind of sorrow that the weather often echoes. When it is raining or the sky is low and heavy, as Baudelaire pounded out in evocation of the hammer blows necessary to build a scaffold, dont most people say it is All Saints Day weather, even if it occurs in the middle of spring?

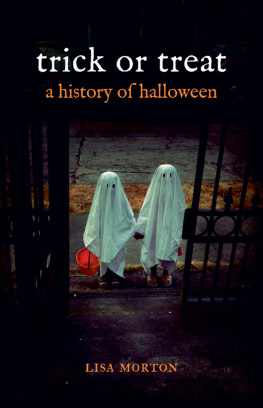

Once the night has grown darker, bizarre apparitions make their appearance. Someone knocks at the door. You open it and find yourself in the presence of a strange mob of boys and girls. Their faces are blackened, or they wear large white sheets or sometimes even grimacing masks and witches hats on their heads, and they all scream lugubrious Boos! for the sake of the person opening the door. And these children are clamoring for cakes, candy, apples, or even a couple of coins. It is in your best interest to give them something, for if you do not, they are capable of casting a curse upon your home and, especially, of returning later in the night to haunt it, disturbing the sleep of the inhabitants or giving them abominable nightmares. Whats this all about?

This is when you spot on your neighbors windowsillif you have any neighbors!an enormous pumpkin that has been visibly hollowed out and had holes carved in its shell depicting eyes and a mouth. Inside, the flame of a candle is dancing to the will of the wind. This depiction brings to mind a grimacing deaths-head, and that produces a gripping effect, all the more so when you realize that all the neighborsif you have neighborshave been given the same order and have acted in the same fashion. Truly, one cannot be faulted for asking just what it all means.

It is not Carnival, nor even Christmas. In fact, one refrains from displaying such grotesque figures at Christmas. The recuperation of the profoundly Christian festival of All Saints Day by a populace that does not have too clear an idea of just what the day corresponds to, though grasps that it concerns a sacred commemoration excluding any morbid or diabolical reference, results in the main focus centering on celebrating and feasting. So you may have some questions, but all at once, you recall that for at least the past two weeks stores have been sporting some strange and fantastic decorations in their windows. It makes for a great rivalry, if not in bad taste, at least in exaggeration. Here are seen dolls depicting All this is complemented by the numerous posters inviting the populace to various balls or demonstrations that smell of brimstone. And of course all the produce merchants have displays offering a huge assortment of pumpkins, some of which have been carved like those that adorn your neighbors windows.

True, this is the privileged season before the chill of winter arrives when these cucurbits of a sometimes impressive volume are cooked, permitting mothers to offer their children those good-for-you squash soups that the young ones accept while making faces behind their mothers backs.

By all evidence, a curious ambience reigns over all of the Western world on October 31, and this ambience, almost completely absent in Europe for almost the entirety of the twentieth century, has enjoyed growing popularity there over the past dozen years, to the extent that its manifestations are becoming an institution comparable to those of Christmas, New Years Day, and, to a lesser extent, because these festivals have weakened considerably, Mardi Gras and Mid-Lent. What we are talking about, of course, is Halloween.

The term evokes nothing for French speakers, who have adopted it nevertheless. It is much more familiar to Anglo-Saxons, on the one hand because it is an Old English word, and on the other hand because this apparent folk festival has never ceased being celebrated in the British Isles and in the United States. The defining feature of folk festivals is to provoke enthusiasm within all classes of a determined society. Such is the case for the mysterious Halloween.

We need first to reflect upon the date: the night preceding the first day of November. This date is no chance selection. And the night following the first day of November, the eve of November 2, corresponds, in the liturgical calendar of the Roman Catholic Church, to the Day of the Dead. That, too, is no accident.

Furthermore, in the general sense, All Saints Daywhich is by its very nature a festival of joyis always confused with the Day of the Dead. This explains and justifies the placing of flowers on tombs, a ritual gesture that is both the manifestation of the memory of those who are no longer and a respectful homage in their honor. What we have here is a kind of ancestor worship that dares not say its name.

The Roman Catholic Church, like the various Protestant churches, has always encouraged, while energetically refusing any reference to ancestor worship, the acts of piety accompanying the first and second days of November. Toussaint (All Saints Day), being literally the holiday of all the saints, whether officially recognized or not, could not be otherwise, inasmuch as Christian dogma assumes that any deceased individual, based on his merits, can be admitted among the Elect. But where the Roman church cannot venture any further is in the profane domain of the carnival-like manifestations of Halloween. This is why, on the eve of All Saints Day in 1999, French bishops published a text severely condemning these manifestations in the name of dignity and respect owed the deceased and the Communion of Saints.

From a logical point of view, this condemnation is perfectly defendable because it denounces the inevitable abuses and excesses that accompany these kinds of manifestations. But from a liturgical point of view, it rings false with respect to the archetypes that have provoked these carnival-like manifestations, on the one hand, and on the other, their appropriate religious recuperation under an abbreviated form by the Church itself, which would have been unable to do otherwise. This is, in fact, to claim that the profane rituals of Halloween are the degenerated remainders of religious ceremonies celebrated within the sanctuary. In reality, as we will see later, it is these oft-decried profane rituals that are at the origin of Christian ceremonies.

Furthermore, it seems that this condemnation on the part of the French bishops is rather late in coming. In the past, the Church has not refrained from intervening in numerous circumstances of public life, even in cases where it was unwarranted. This was the case for Father Christmas, who was deemed pagan and yet was a widespread presence in Christian families. It is true that the Roman Catholic Church joined here with the Protestant churches, mainly the Calvinists, for whom all festivals, including celebrations, are not only useless but also pernicious, because they divert the individual from what should be his sole concern: ensuring his salvation. The festival forms part of those deceptive powers that, according to French philosopher Blaise Pascal, raise a smokescreen between daily life and its supreme objective. Finding themselves incapable of eradicating festivals of any kind, Christianity bent its combined efforts to endeavor to channel and give them a finality in accord with its fundamental dogmas.

Next page