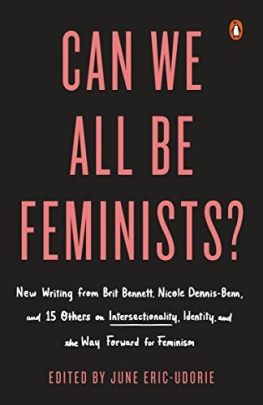

penguin.co.uk/vintage

For my grandparents, Paul Kofi, Ophelia Joyce,

John and Ann, whose stories have inspired mine.

In memory of Alexander, whom we called King, gone too soon.

To Naya Ketawa. This is for you.

The ache for home lives in all of us, the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.

Maya Angelou,

All Gods Children Need Travelling Shoes

INTRODUCTION: IDENTITY LESSONS

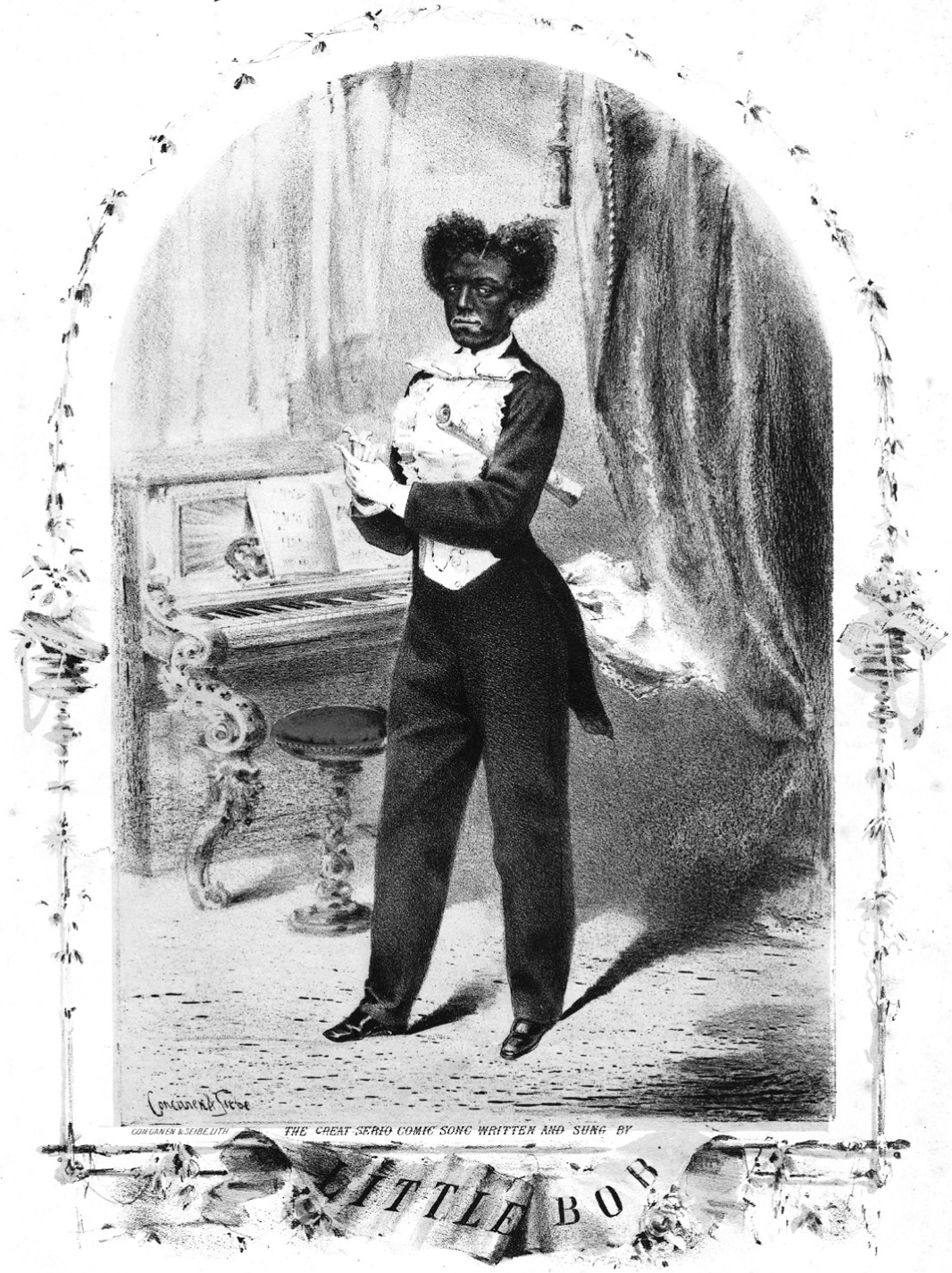

British sheet music cover, c. 1850. Minstrels were a popular form of entertainment in Victorian music halls, and were broadcast on the BBC until the 1970s.

The world is wrong. You cant put the past behind you. Its buried in you; its turned your flesh into its own cupboard.

Claudia Rankine,

On a Friday evening in October 2004, with the nights drawing in and the layers piling up over summer clothes, I was sitting cross-legged in the living room of my friend Mirandas house in east London. I had recently returned from living in Senegal, one of the last frontiers of Africa before it stabs into the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and melts into the Sahara Desert in the north. Two years earlier, Id barely had time to say goodbye to these university friends Id given myself a few days to recover from the exhaustion of my final exams, packed two large suitcases, then boarded an Air France flight, twenty-one years old, impatient to begin the journey into my new, African identity. It was a journey that had been years in the planning.

The friends gathered round on this autumn night had treated my return much as they had my departure: curious, but unsurprised. I came bearing stories of unpredictable work in countries that most British people have barely heard of Chad, Burkina Faso, So Tom of trying to hold meetings with government ministers in languages I could barely speak, of only just surviving cerebral malaria, of smuggling suitcases of cash into war zones. My friends, deep in the hustle of Londons graduate job market, pointed out how fortunate I was to be able to decorate my CV with this kind of experience. But that had never been the reason for going. I hadnt left Britain to become an expat with a competitive advantage in the job scrum; I had left Britain to leave being British. I believed that relocating my future to one or more of Africas many nations would solve the problems of belonging that had nibbled away at me, a mixed-race girl growing up in Britain, for as long as I could remember. I had not meant to come back, not after two years, not ever, but to settle in West Africa for good, and take up my place in the world as a proud African, in places where I thought I would fit in.

Exactly the opposite had happened. Living in Senegal I had discovered, to my endless confusion, how British I was. Returning to London meant the relief of familiarity, of home, but the painful reminder that home was a place that had surveyed me as alien, questioned me about my background, and expected me to provide explanations. Very little, it seemed, had changed.

Evenings like this, in the little house that marked the beginning of a steep staircase of Victorian terraces descending down to the River Lea and the bleak London marshland beyond, were different. These friends and I a group of black, mixed-race and other misfit Oxford graduates, sitting in a loose circle on the carpet were bonded by the fact that none of us had ever really fitted in. So we would congregate there, feasting on vegan food, painfully aware of the clichs and contradictions that we embodied, and trying to work out the point of it all. Id longed for this companionship while Id been away, and the rhythms of our London lives, the quirkiness of our homes and our clothes and our seasons, the cynicism and sarcasm of our humour. Now I was back in the midst of these traditions, and drinking them in like warm tea.

I was in love with a man Id met not long before Sam who lived just a mile away from Miranda in Tottenham, a part of London he always described as the hood. This environment had shaped him into a person unlike any I had ever met before, and having returned to it from a northern university where hed spent three years getting a law degree, he now clerked at a solicitors firm during the day, saving up money before starting the vocational course to become a barrister. He spent each evening after work on the athletics track near White Hart Lane, where he trained as a sprinter, lumps of lactic acid layering themselves onto his thighs hour upon hour. Unlike any other 24-year-old I knew, Sam had his own car, a source of independence for which he spent years working, and he was always on the move late at night, plugging away at the personal development books he credited with sparing him the same fates as his friends. It never ceased to shock me how many of the people he grew up with were in jail, or in and out of mental institutions, or stuck in minimum-wage jobs. And in his community, he seemed to know everyone.

That night, Sam was visiting a school friend who lived on a nearby council estate further up Mirandas road, a sprawl of decaying social housing at the top the hill. Neither of us could have known that this was the last time Sam would visit. Just a few weeks later his friend was dead, caught up in crossfire from a turf war. These werent innocent times his friend was already getting slowly drawn into the drug trade, the one industry that provided many local jobs. But for a few hours that evening it was like the old days, before Sam had gone away to university and left his friends behind; just hanging out with his boys on the block, catching up.

Since he was so close by, Sam offered to pick me up from Mirandas house, and drive me home to Wimbledon, where I lived, around seventeen miles across town. Just before midnight, he rang the doorbell. The scene had already played itself out in my mind I was excited about introducing my friends to this man they had heard so much about. I pictured him coming in, joining our little circle, sharing some tofu cheesecake.

That, however, is not how it went down. Miranda opened the door, and Sam said hello to her, cautiously, as he stepped through that front door and into the room with the big bay window, the cluttered piano. Once inside, he stopped dead, as if in shock, and stared. He shifted from foot to foot, mumbling hello, and gazed around in bewilderment, taking it all in. Sam, so confident, so uneasily fazed, was quiet, and perplexed. In all his life, he told me later, he had never seen a scene like this people talking so earnestly, almost conspiratorially, in low, hushed voices, even eating the way we were eating, an array of strange plant foods being passed around on little plates.

Thirteen years later, we still talk about that day.

You lot, sitting there with your herbal tea, all round in a circle, nah! Sam shakes his head. That blew my mind! And I mean I thought Id seen it ALL! What was so strange about it? I ask. You dont understand. He shakes his head again. This area is hood, you know! People getting shot in the area, man, dem on the hustle. And you lot were sitting there oblivious, all huddled around. In Wimbledon, yeah, fine. But in my area, and you still behaving the same way? I would never in all these years growing up around here have known that that scene could have even existed in this area

There was something else that bothered Sam at the time. He had his own preconceptions about my group of friends. He knew we had been to Oxford, and that many of us were privately educated, some at elite boarding schools. Now we had our degrees in the bag, we represented everything he and his friends had never had access to, a kind of uniform privilege that, as far as he was concerned, meant that success for us was guaranteed with as much certainty as failure was for most of the people around him.

Next page