TIME AND POWER

The Lawrence Stone Lectures

Sponsored by:

The Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies and Princeton University Press

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book.

Time and Power

VISIONS OF HISTORY IN

GERMAN POLITICS, FROM

THE THIRTY YEARS WAR

TO THE THIRD REICH

Christopher Clark

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2019 by Christopher Clark

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018960827

ISBN 978-0-691-18165-3

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Brigitta van Rheinberg, Amanda Peery, and Eric Crahan

Production Editorial: Brigitte Pelner

Jacket Design: C. Alvarez-Gaffin

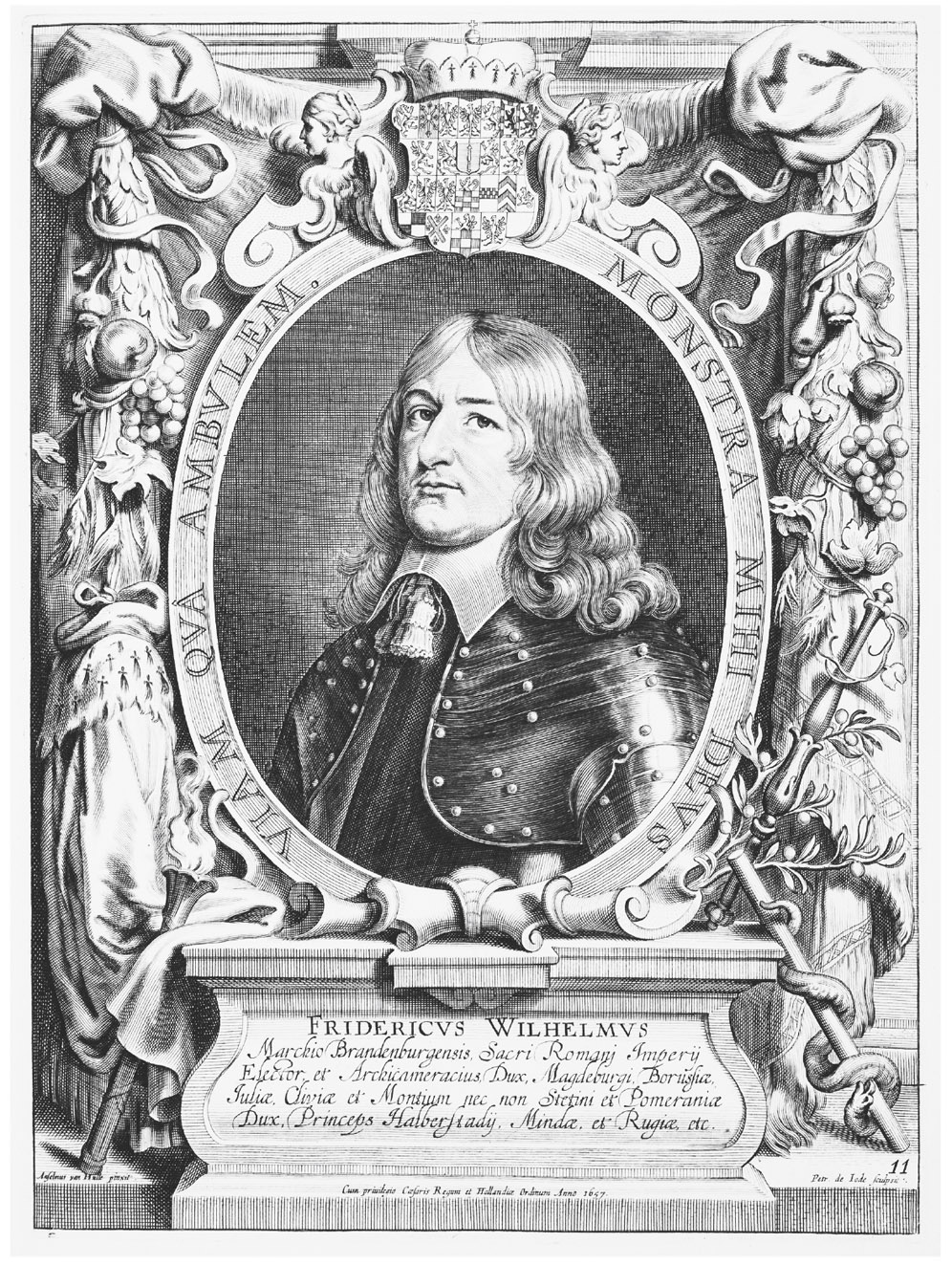

Jacket/Cover Credit: Jacket Images (left to right): 1) Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, 2) Frederick II, 3) Otto von Bismarck, 4) Adolf Hitler

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: James Schneider

Copyeditor: Joseph Dahm

This book has been composed in Miller

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Kate and Justin Clark, siblings for all seasons

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

IN THEORY, the pool of intellectual debt ought to shrink with each new book, as one grows older and more independent. In my experience, the opposite has been the case. As you get older, you get less shy about asking for help and you venture further into terrain where you depend on the guidance of others. This book could not have been written without the encouragement, conversation, and advice of many friends and colleagues. Special thanks go to the following, who read all or part of the manuscript and offered detailed comments and stimulating suggestions: Deborah Baker, David Barclay, Peter Burke, Marcus Colla, Amitav Ghosh, Oliver Haardt, Charlotte Johann, Duncan Kelly, Jrgen Luh, Annika Seemann, John Thompson, Adam Tooze, Alexandra Walsham, and Waseem Yaqoob. As then-anonymous reviewers for Princeton University Press, Franois Hartog, Jrgen Osterhammel, and Andy Rabinbach made enormously helpful comments on the manuscript. Nora Berend, Francisco de Bethencourt, Tim Blanning, Annabel Brett, Matthew Champion, Kate Clark, Allegra Fryxell, Alexander Geppert, Beatrice de Graaf, Paul Hartle, Ulrich Herbert, Shruti Kapila, Hans-Christof Kraus, Jonathan Lamb, Rose Melikan, Bridget Orr, Anna Ross, Kevin Rudd, Magnus Ryan, Martin Sabrow, and Quentin Skinner all offered precious advice on specific issues or passages of text. Nina Lbbrens writing and thinking about time and narrative in art have shaped the book in many ways. Josef and Alexander, once happy distractions from the work of writing, have grown into thoughtful conversation partners whose insights nudged me through various bottlenecks. Kristina Spohr read and commented on the text at many stages in its evolution and sustained its author with criticism, advice, and companionship.

The History Department of Princeton University gave me the opportunity to develop the ideas explored in this book by inviting me to present the Lawrence Stone Lectures in April 2015, and my thanks go to Brigitta van Rheinberg of Princeton University Press for her encouragement of this project from its inception and Brigitte Pelner, Amanda Peery, and Joseph Dahm for help with the preparation of the text for publication. I am grateful to my colleagues at the History Faculty of the University of Cambridge and at St Catharines College, and to one in particular, Sir Christopher Bayly, who died in April 2015. Even now, whenever I walk into the main court of St Catharines of an afternoon, I look across to the window of C3, on the off chance that Chris might be leaning in his shirt sleeves on the window sill and invite me up for a drink. The conversations that followed always led to unexpected places.

Time is an elusive but also an inescapable subject matter, especially now that the relationship between past, present, and future has become such a central preoccupation of politics and public discourse. In times of flux, the most lasting things acquire heightened value, which is why I dedicate this book to my sister Kate and my brother Justin, who were there (almost) from the start.

FIGURE 1.1. Frederick William, the Great Elector, engraving by Pieter de Jode from a portrait by Anselmus van Hulle. Source: Anselmus van Hulle, Les hommes illustres qui ont vcu dans le XVII. sicle (Amsterdam, 1717).

Introduction

AS GRAVITY BENDS LIGHT, so power bends time. This book is about what happens when temporal awareness is lensed through a structure of power. It is interested in the forms of historicity appropriated and articulated by those who wield political power. By historicity I do not mean a doctrine or theory about the meaning of history, nor a mode of historiographical practice. Rather, I use the term in the sense elaborated by Franois Hartog to denote a set of assumptions about how the past, the present, and the future are connected.

The book focuses on four moments. It opens with the struggle between Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg-Prussia (162088), known as the Great Elector, and his provincial estates after the end of the Thirty Years War, examining how these disputes invoked starkly opposed temporalities and tracing their impact on the emergent historiography of Brandenburg-Prussia. The Electors reign was marked, I argue, by an awareness of the present as a precarious threshold between a catastrophic past and an uncertain future, in which one of the chief concerns of the sovereign was to free the state from the entanglements of tradition in order to choose freely between different possible futures.

The focuses on the historical writings of Frederick II, the only Prussian monarch ever to have written a history of his own lands. It argues that this king consciously retreated from the conflictual view of the state expounded at the court of his great-grandfather, the Great Elector, and that this departure reflected both the changed constellation of social power sustaining the Prussian throne and Fredericks idiosyncratic understanding of his own place in history. In place of the forwards-leaning historicity of the Great Elector, I suggest, Frederick imagined a post-Westphalian condition of stasis, embracing a neoclassical, steady-state temporality in which motifs of timelessness and cyclical repetition predominated and the state was no longer an engine of historical change but a historically nonspecific fact and a logical necessity.

the interplay between the forces unleashed by the revolutions of 1848 while at the same time upholding and protecting the privileged structures and prerogatives of the monarchical state, without which history threatened to degenerate into mere tumult. It argues that Bismarcks historicity was riven by a tension between his commitment to the timeless permanence of the state and the churn and change of politics and public life. The collapse in 1918 of the system Bismarck created brought in its wake a crisis in historical awareness, since it destroyed a form of state power that had become the focal point and guarantor of historical thinking and awareness.

Among the inheritors of this crisis, the argues, were the National Socialists, who initiated a radical break with the very idea of history as a ceaseless iteration of the new. Whereas Bismarcks historicity had been founded on the assumption that history was a complexly structured, forwards-rushing sequence of ever new and non-foreordained situations, the Nazis plinthed the most radical aspirations of their regime on a deep identity between the present, a remote past, and a remote future. The result was a form of regime historicity that was unprecedented in Prussia-Germany, but also quite distinct from the totalitarian temporal experiments of the Italian fascist and Soviet communist systems.