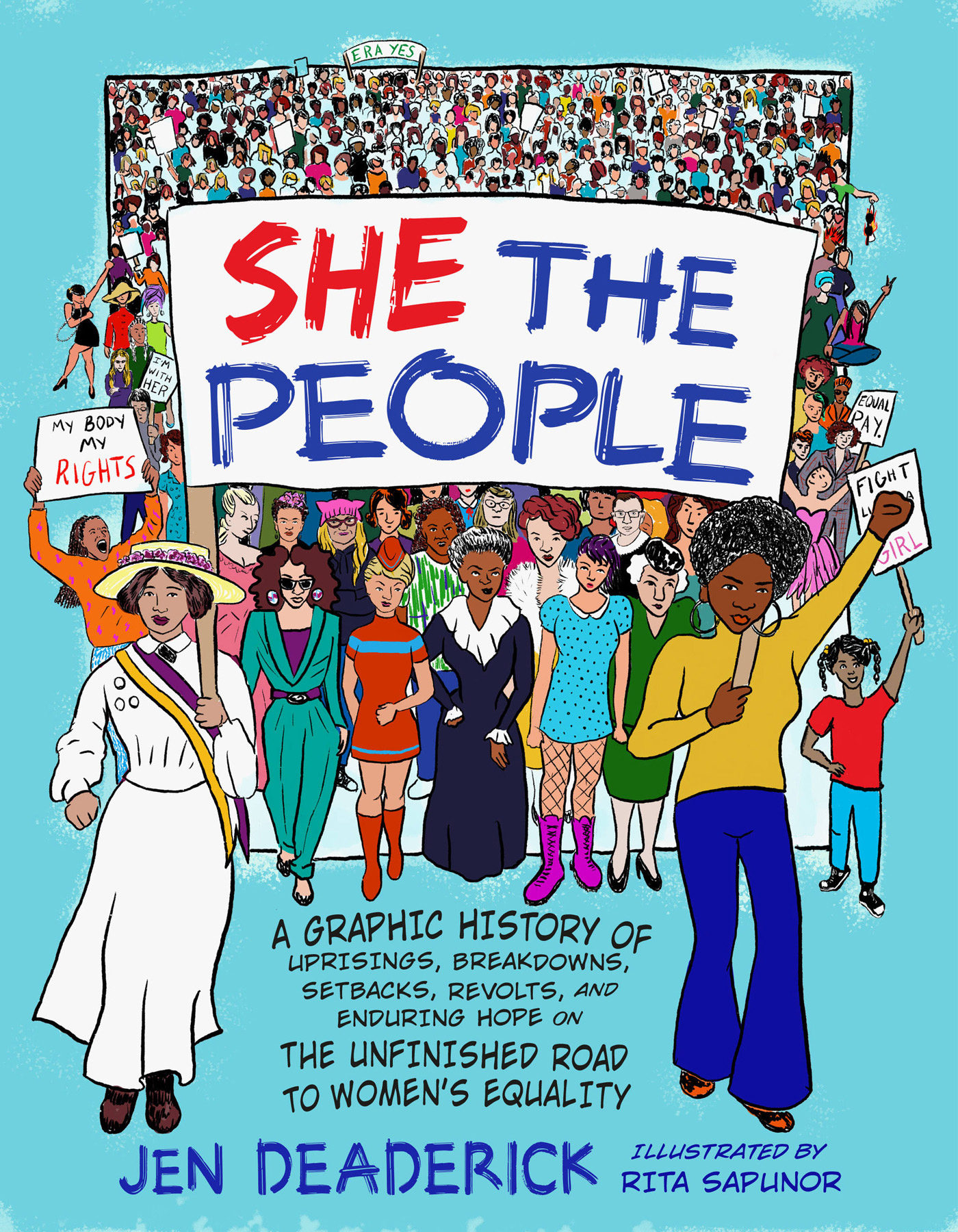

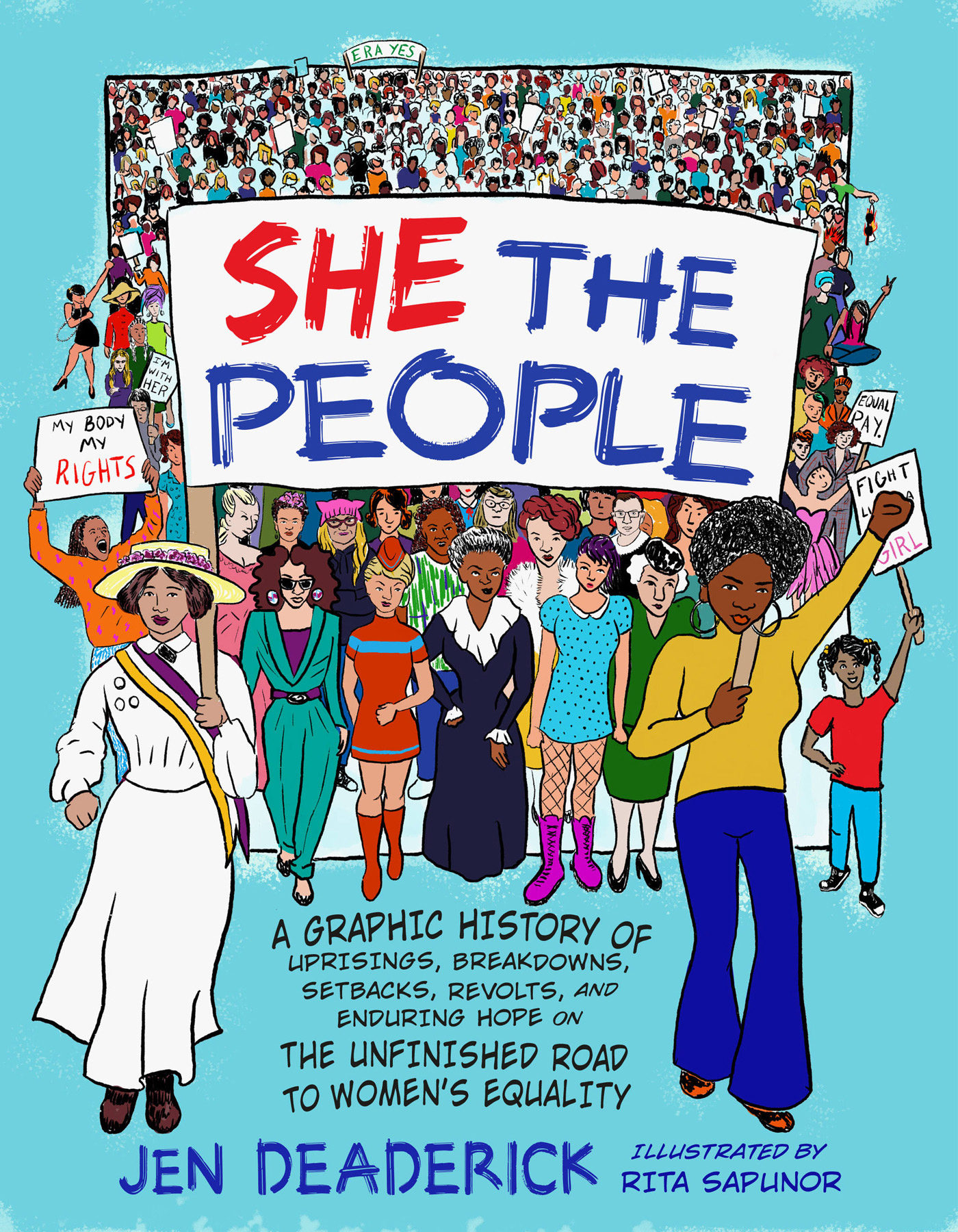

Copyright 2019 Jen Deaderick

Illustrations by Rita Sapunor. All rights reserved.

Cover design by Alex Camlin

Cover image by Rita Sapunor

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Seal Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

sealpress.com

@sealpress

First Edition: March 2019

Published by Seal Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Seal Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-1-58005-871-1 (paperback), 978-1-58005-872-8 (ebook)

E3-20190129-JV-NF-ORI

For the two Rosalinds and my mother, Ann, who made sure I knew about Victoria Woodhull

T HE NEWS OF THE DECLARATION spread rapidly. Copies of the document had been printed immediately, and riders distributed them all over the colonies. Embarrassingly, an overly enthusiastic patriot in tiny Worcester, Massachusetts, not yet an industrial powerhouse, intercepted a copy en route to Boston and read it aloud to a private crowd, but the event in Boston on July 18, two weeks after the signing, was still special.

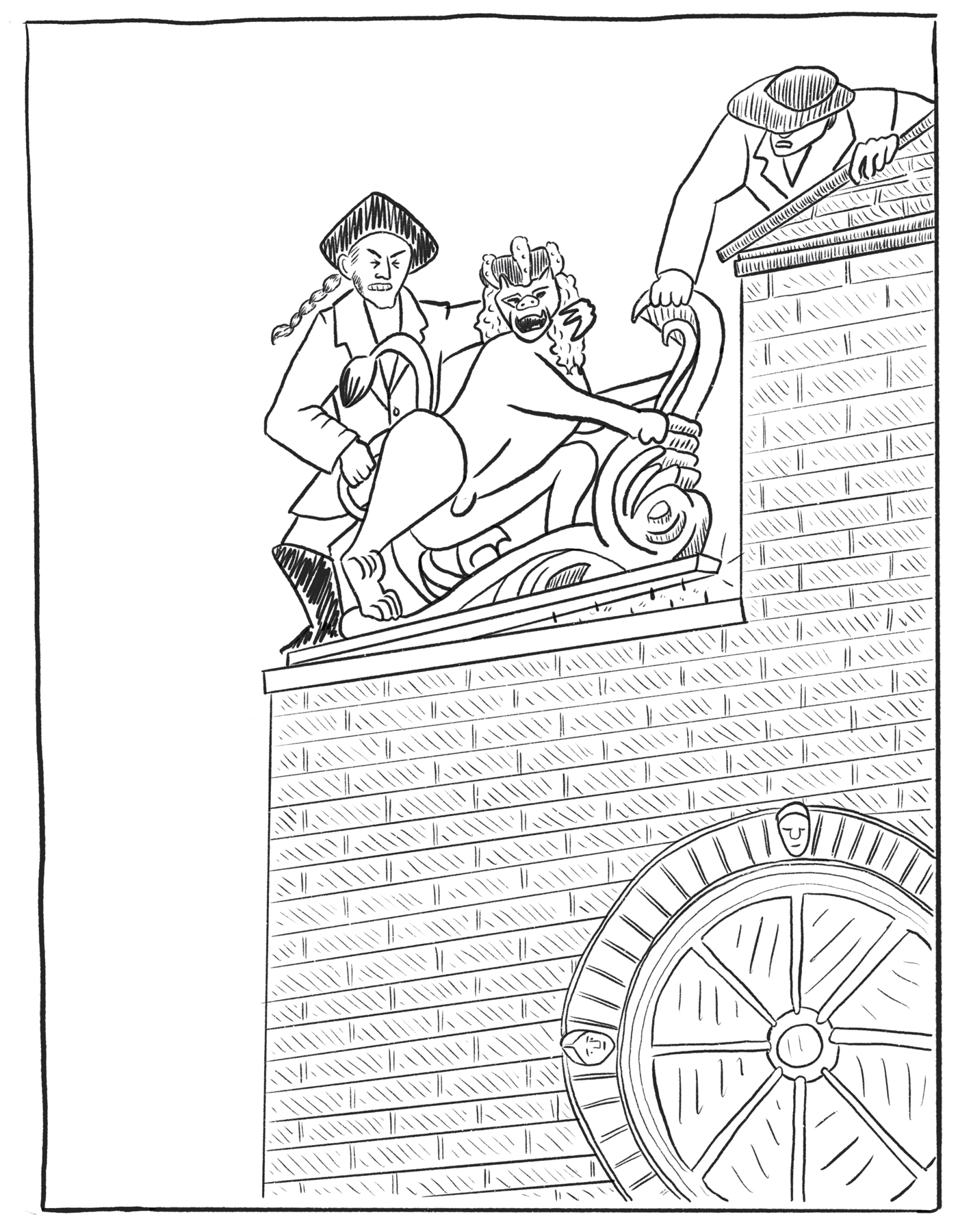

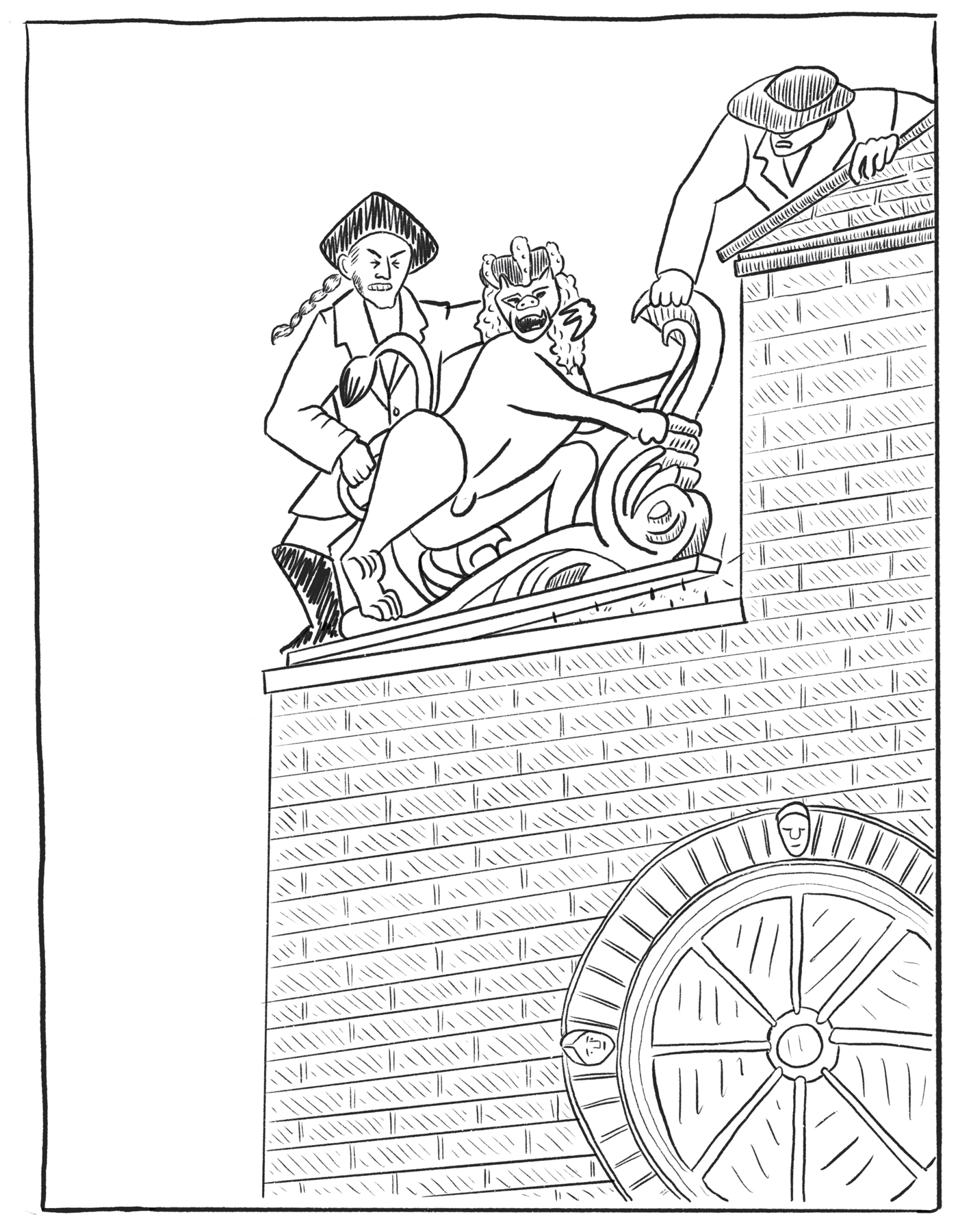

THE DECLARATION was read from the balcony of the Town-House, the seat of the Massachusetts colonial government, overlooking the very spot where, just two years earlier, rioters had been shot and killed by British soldiers in what became known as the BOSTON MASSACRE. The Town-House was where the colonial legislature met, and statues of a lion and a unicornsymbols of the Crown and reminders to the citizens of Boston of whose royal decree they ultimately lived underadorned its roof. The building sat atop a hill that rolled gently down to the harbor, just a half mile away. After the REVOLUTION, it would be claimed as the State House, the meeting place of the state legislature.

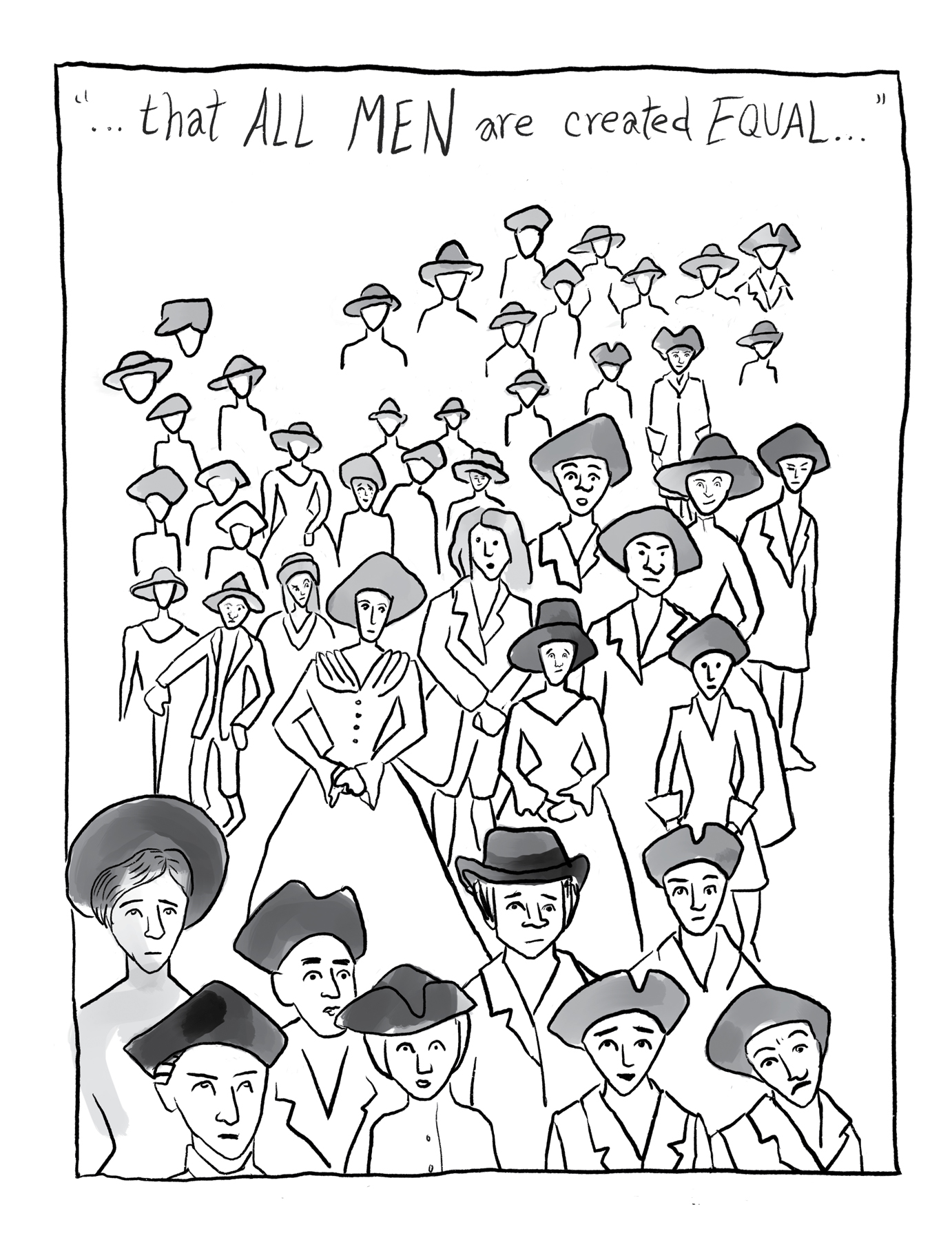

The crowd was mixed. Sailors from around the world mingled with Black and White residents of the city in the bustling markets surrounding the square, though the recent military occupation of the agitated and rebellious city had reduced their number.

And, of course, many of the people in the square that day were womenwomen are always in all of these stories whether their presence is noted or not. That day, more women than usual came to witness history happening.

ABIGAIL ADAMS, whose husband would later become president, was in the crowd, and described the scene in a letter to her husband a few days later, using the irregular spelling of the day:

Last Thursday after hearing a very Good Sermon I went with the Multitude into Kings Street to hear the proclamation for independance read and proclamed. Some Field peices with the Train were brought there, the troops appeard under Arms and all the inhabitants assembled there (the small pox prevented many thousand from the Country). When Col. Crafts read from the Belcona of the State House the Proclamation, great attention was given to every word. As soon as he ended, the cry from the Belcona, was God Save our American States and then 3 cheers which rended the air, the Bells rang, the privateers fired, the forts and Batteries, the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed and every face appeard joyfull.

Of course, we know which words kept the crowd rapt: the opening sentences that broadly and assuredly speak of human events and the dissolution of political bonds. The magnificent list of grievances against the king. The pledging of lives, fortune, and sacred honor. Ringing bells and blasting cannons were the only way to follow the reading.

Bostonians, always looking for a good excuse to riot, climbed onto the roof of the Town-House and tore down the symbols of the Crown, the lion and unicorn. Consent of the governed, indeed.

But its the opening of the second paragraph that changed everything. Its what still rings in our ears more than two centuries later:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The audacity is astounding. We know it now as a promise still unfulfilled, but for the men of the time to declare that they and all other men were equal to a king and were created that way was bold as hell. Most people on the planet lived in societies in which some inbred family claimed some cosmic force had decided they should be in charge, and everyone had to go along with it until the monarchs were beheaded. So, pause for a moment and raise your glass to inalienable rights.

THAT BEING SAID

The men who wrote the Declaration of Independence didnt really believe that ALL men were equal. The statement is largely a rhetorical flourish produced by a group that included a fair number of enthusiastic owners of slaves. What they really meant in the Declaration by all was landowning White guys like themselves. The men part, however, they totally meant.

The colonists spent the next eight years fighting a bloody war of independence against the Crown while debating exactly what this new country would look like. After the initial printing of the Declaration had gone out, the Continental Congress commissioned firebrand Baltimore printer and postmaster MARY KATHERINE GODDARD to create a more compelling edition, this one with the signatures attached, giving it a powerful punch.

This copy spread everywhere, and a radical womans name imprinted at the bottom made the Declaration an even hotter topic of discussion around the colonies. While the War of Independence raged on, the citizens of this country-to-be hammered out how to make states out of colonies.

Massachusetts, always the nerdy overachiever, had a constitution drawn up even before the war was over. The first draft in 1778 was widely rejected, in part because it upheld the institution of slavery and limited the rights of Free Blacks. Another version of the states constitution that included the words all men are born free and equal was introduced, and that one was ratified in 1780.

Constitutions, however, are just symbolic pieces of paper if no one tests them in the courts.

In the early 1780s, ELIZABETH, an enslaved woman also known as MUM BETT, heard the talk around the dinner tables she served of men being born free and equal and of certain inalienable rights. Her owners were enthusiastic supporters of the Revolution. One day, the wife, enraged, struck at Elizabeths younger sister with a hot iron. Elizabeth jumped between them to take the blow and suffered severe burns on her upper arm.