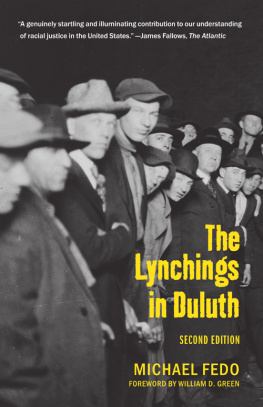

The Lynchings in Duluth

SECOND EDITION

The publication of this book was supported through a generous grant from the June D. Holmquist Publications and Research Fund.

1979 by Brasch and Brasch, 1993 by Michael Fedo. New material 2000, 2016 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 551021906.

www.mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-013-5 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-014-2 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fedo, Michael W., author.

Title: The lynchings in Duluth / Michael Fedo ;

with a foreword by William D. Green.

Other titles: They was just niggers

Description: Second edition. | Saint Paul, MN : Minnesota Historical Society Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015045628 | ISBN 9781681340135

(pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681340142 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: LynchingMinnesotaDuluthHistory20th century. | Duluth (Minn.)Race relationsHistory20th century. Classification: LCC HV6462. M6 F4 2016 | DDC 364.1/34dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015045628

IN MEMORIAM

Elias Clayton (19011920)

Elmer Jackson (19011920)

Isaac McGhie (19001920)

DEDICATION

for my mother

Ramona Fedo (19141977)

who first told me

about this incident

Foreword

WILLIAM D. GREEN

In Duluth, Minnesota, during the summer of 1920, between five to ten thousand people clogged the street in front of the police station to witness the hangings of three black men. Reporters of the two major newspapers of Minneapolis and St. Paul shocked their readers with lurid accounts of the event. In fact, leading newspapers throughout the North vilified Duluthians for having stained their citys good name and castigated them for being no better than southern racists. Gov. Burnquist, then president of the St. Paul chapter of the NAACP, had commissioned his adjutant general to launch a formal investigation. Three dozen men were indicted for being in the mob. And one year later, in reaction to the event, the state legislature enacted an antilynching law. Yet, by 1992, it was as if the event had never occurred. I had never heard of the incident. No one I knew had heard of it. For most Minnesotans, the intervening years since the lynchings would obliterate their collective memory, leaving a diminishing handful to treat it, like all dirty little secrets, as something best left unspoken. It was then when I heard that a book by writer Michael Fedo recounted the event, but that the book was hard to find. None of my usual sources could help me locate a copy since it had been long out of print. However, through the tenacity of a bookseller friend whose avocation was tracking down out-of-stock books, I eventually was able to obtain a copy.

What I read was an astonishing chronicle of an event that defied everything I thought I knew, not only about lynch mob mentality, but about my adopted state of Minnesota. Indeed, the scope of the incident was as tragic as it was unbelievable. During that period the lynching of black men was typically a rural, southern phenomenon and conducted with impunity, and the Duluth incident was none of these (although only three of the lynchers were convicted and only for the crime of rioting). I was impressed with the sober treatment in which Fedo wrote the account, letting the facts speak for themselves devoid of self-righteous melodrama. I was impressed with the care he took in recounting the small but telling stories of individual participants and observers in a manner that cast them as ordinary people caught up in an extraordinary moment. Unfortunately, the work did not include footnotes, and this concerned me; but as a result of my own study into the legal and social consequences of the lynchings on the city, I have found myself able to vouch for the accuracy of Fedos research. It is an account on which the reader can rely and a story that needs to be told.

My own department of history at Augsburg College agreed with me when I wanted to hold a Day In May program with the Duluth lynchings as the theme. Not since the early seventies had the college used the first day of May as a time dedicated to serious discussion and reflection. Instead, over the years the Days observance evolved into a time for fun-filled celebration that heralded the arrival of spring and the end of classes, complete with balloons, loud music, and the fatted calf of college cuisinecheap hot dogs and pizza. It hardly seemed a time for examining such a somber topic. Nonetheless, we put together a panel of speakers, which included Fedo, posted notices around campus, and secured a moderate-size room for the occasion. Because the day of the event was warm and sunny, and the discussion was to convene in the afternoon, no one expected many to attend. Already you could hear the persistence of bass guitars and drums booming from speakers in Murphy Park across the street when I entered the room, but what I found inside was stunning: it was standing-room only. Students, faculty and staff, and a sizable number of retirees filled the room. Though we hadnt determined how long the discussion should last, I think we all anticipated that after an hour people would begin to leave. However, the discussion, in which the audience later participated, lasted for an astonishing three and a half hours. The topic proved to be not only one that was important to share but one about which people wanted to learn.

I think the importance of the book also is in its potential for serving as a device through which we can examine the terrible quandary of moral dilemma. Under horrific circumstances, would one exert strength in following a moral directive or choose to go with the crowd? As Fedo asked me over lunch recently, if one of us was the young man who had climbed the streetlamp in order to get a better view, how would we have responded when the large crowd of men, some of whom we knew, beckoned us to secure a rope that would be used to hang a man we didnt know? At what point is ones guilt by association manifest? When he fastened the rope? When he climbed the streetlamp? When he went downtown? In the false security of hindsight is it fair to judge him? Indeed, is it fair to ourselves to be judgmental? In asking such questions, will we learn enough about the forces that incite the bestial quality within our collective soul? Given the presence of dislocating forces on society that emanate from social, political, and economic forces, can we distinguish individual responsibility from the communitys? Is vigilance against mob action the central lesson that we must learn? And if so, can our society ultimately advance if vigilance keeps us from talking about race? The importance of Fedos work comes from the opportunity it provides by challenging us to navigate, as Homers Ulysses did, through straits made tempestuous by the twin demons Scylla and Charybdis.

During one of my weekly walks with a colleague from Augsburg, I began telling him of a tragic racial encounter in history that I was then researching. Although I was using hima strong analytical thinker as well as a very good writer (notwithstanding his training as an accountant)as a sounding board for some of the prickly issues I wanted to explore in an article I was struggling with, I was unmindful of how he was reacting to my anecdotes. Indeed, I was surprised when he told me how disturbed he felt at what I was saying; that otherwise reasonable people were capable of performing the most bestial acts imaginable, being motivated to do so not so much in the name of white supremacy but too often by far more banal instincts; that it happened so often, in so many different settings, at any prompting; and that such acts occurred with impunity. How could I live with such knowledge, he wondered. Didnt it leave me haunted? Didnt it fill me with rage? How on earth could I endure functioning as a scholar and teacher without giving in to the dark temptation of becoming an ideologue?

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.