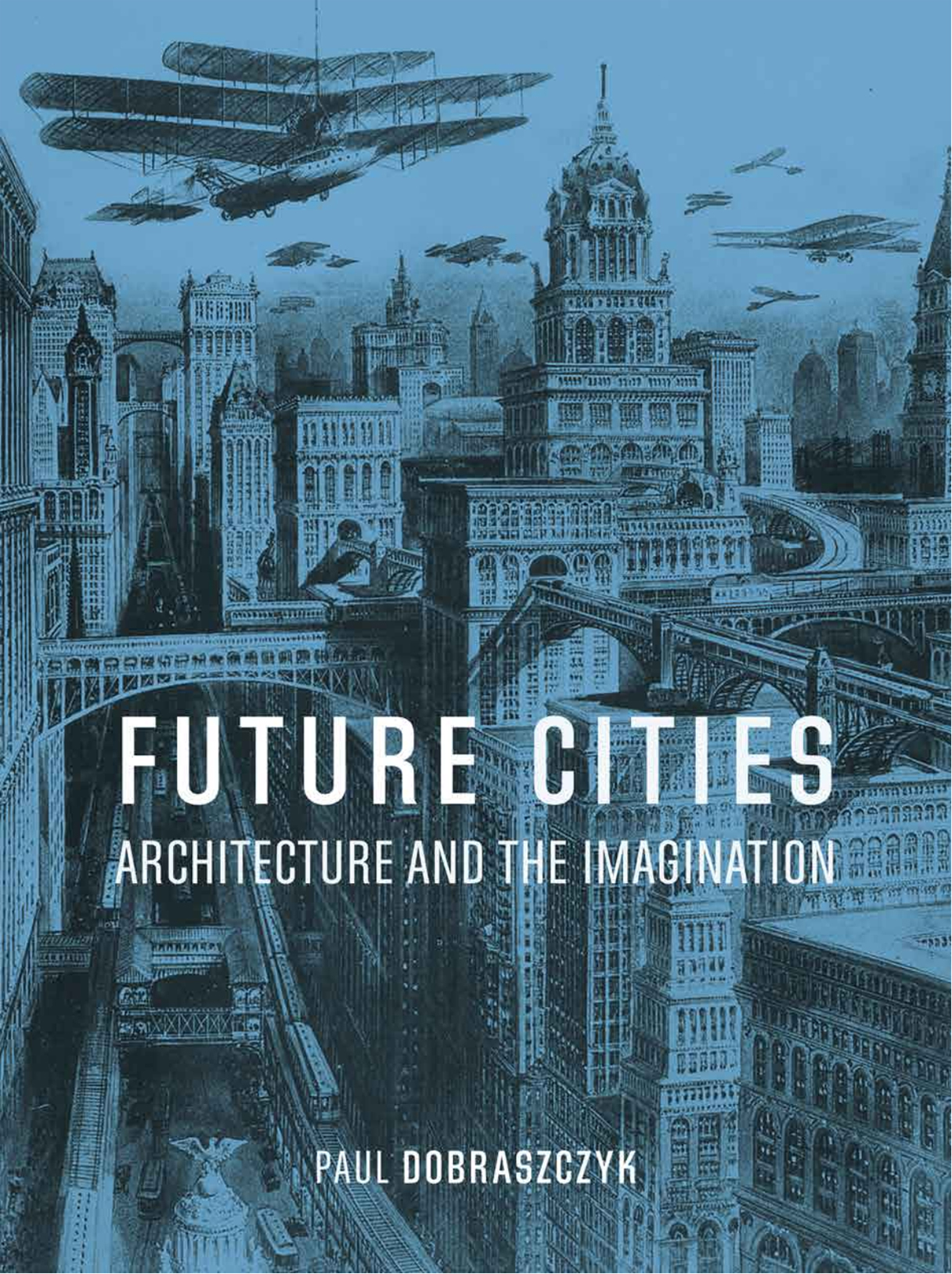

FUTURE CITIES

FUTURE CITIES

ARCHITECTURE AND THE IMAGINATION

PAUL DOBRASZCZYK

REAKTION BOOKS

To my father

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright Paul Dobraszczyk 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789141047

Contents

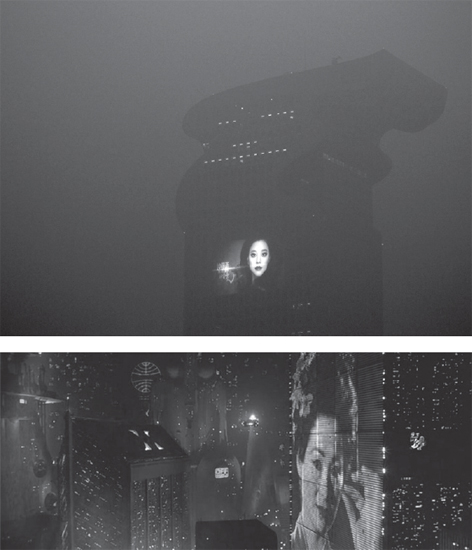

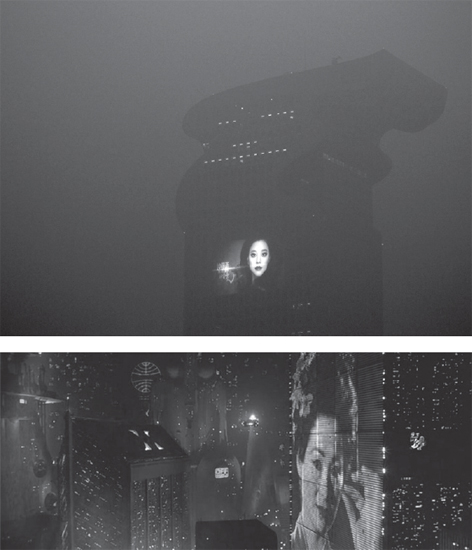

Photograph of a projected image on a high-rise building in Beijing in 2013 (top), compared with a shot from the 1982 film Blade Runner (bottom).

Introduction: Real and Imagined Future Cities

I n January 2013 a photograph of a projected image on a smog-enshrouded high-rise building in Beijing became an Internet sensation because it seemed uncannily reminiscent of the urban landscape seen in the 1982 film Blade Runner.

The fundamental way in which we make sense of the future is through the imagination: to think of the future is, by necessity, to imagine it. Yet so much of current thinking on the future of cities is instrumental in its nature, drawing on science-based predictions to map out possible scenarios and separating this empirical data from the rather more subjective predictions stemming from the creative imagination. Cities are always a meld of matter and mind, places that we are rooted in both physically and mentally. Furthermore, in the digital age, the real and the imagined are already thoroughly intertwined why else, after all, would tourists now be offered Blade Runner tours? Rather than cleave the imagination from reason, should we not explore how the two are entangled how together they can open up rich possibilities in terms of how we think the future?

This book aims to do precisely this, by bringing together visions of future cities from the nineteenth century to the present day in all their many and varied forms: in literature, art, architectural imagery, cinema and video games. The central aim of the book is to ground these imaginary cities in architectural practice, demonstrating just how many connections can be made between the two. It will show that images of the future, no matter how fantastical they may be, are really about the present moment a way of changing current thinking and practice in order to set them on a different course or courses. The book organizes representations of future cities into three thematic areas unmoored cities (submerged, floating and flying), vertical cities (skyscrapers and undergrounds) and unmade cities (ruins and salvage) each of which presents a range of examples that relate to real issues confronting urbanists and architects today. These include flooding generated by climate change, rapid population growth and increasing social division, and technological failure and societal collapse, whether imagined or otherwise. At its heart, the book aims to reveal the vital ways in which the imagination impacts on how we think through urban futures and how those can and do link with how cities are designed and lived in today. This is to bring the imaginary back into contact with the real or rather to show how embedded the imaginary already is in the real a futurism grounded in the present and in practices of many kinds.

Imaginary Cities

To imagine is to present in your minds eye something that is absent. Its a conjuring act a form of magic in which new images are revealed to the person who imagines.

But what has the imagination to do with cities cities after all being made out of materials that we can sense directly? It is no accident that the explosion of literature about cities in the nineteenth century coincided with the rapid growth of cities themselves, particularly those affected by industrialization, such as London, New York and Paris. Once a city becomes so large and complex that it exceeds ones The London described in Charles Dickenss novels is a city that melds imagination and reality a kind of mental projection of the city superimposed over the real one. And we now experience London as a product of Dickenss texts, whether by engaging in walking tours taking in his literary landmarks or by feeling the atmosphere of the city at certain times as somehow Dickensian. A similar transference of imagined to real is now happening in the Blade Runner tours currently being offered to tourists visiting Shanghai. For every city we visit, we bring a prior imagination of that city, whether formed through paintings weve seen, films weve watched, novels weve read or, more prosaically, through the guidebooks and maps we consult before setting foot on the ground. Think of Kafkas Prague, New York in the films of Woody Allen or Paris in Victor Hugos Les Misrables and its long-running musical counterpart. Indeed, many cities are dependent on the tourism generated by such texts, films and other images; not just in terms of the popularity of their landmark sites or museums dedicated to literary figures, but in the sense of the whole city infused by an imaginary that attracts.

Clearly, then, the imagination is important in how cities are perceived and experienced; but how might it affect those that masterplan cities, namely architects and urban planners? First, both architecture and urban planning begin by seeking to picture what the city might become; that is, they imagine new possibilities for cities. Although architectural designs have to negotiate a host of constraints that simply dont apply to authors or film-makers, they are still fundamentally imaginative works in that they visualize something that does not yet exist. Architectural visualization especially in the digital age relies upon images as tools of persuasion that effectively present something that is essentially a speculation, a fiction. Yet such images often fail to make us feel anything about their possible effects on the city. In the same way as the hyperrealism of CGI effects in blockbuster films often leave us cold, many architectural visualizations try to cover over the gap between fantasy and reality. But it is precisely this gap that allows the imagination to function it alerts us to the difference between fiction and fact; between the world as we find it and the world as we want it to be. As this book will demonstrate, there are countless ways in which architectural projects can be connected to the stories in novels and films, thus enriching their potential to situate us in the built environment they are imagining.

The imagination is both an active agent a way of constituting something and also a transformative faculty. When the imagination is at work, what is produced is not an image that bears no relation to the existing world, but rather a reworking of some image that already exists. In other words, there can be no imagination without a past; no conception of what is to come without what has already been. In this sense, history is critical as to how the imagination projects itself into the future: the desire for a good city in the future already exists in the imagination of the past. Whatever the true model for the Burj Khalifa, its design shows how the architectural imagination builds upon itself in a gradual process of accumulation, rather than through any clear breaks with precedent. Bringing past, present and future together in the imagination of future cities has the potential to significantly enrich how we think about the relationship between the speculative and real, and between what has been, what is, and what is to come.