Table of Contents

ALSO BY ANDREI CHERNY

The Next Deal

G. P. Putnams Sons New York

TO STEPHANIE,

WHO MAKES MY LIFE SWEET

Two middle-aged ladies were sitting at the table behind me that day, the only other customers of the meal. They had come, they said, because when the Americans liberated Paris, a young American lieutenant had slept in their house. He had brought coffee, soap, food, butter when all Paris hungered at the mention of them. When he moved off with his company they asked him what they could do to repay him. He said there was nothing they could do for him, but if, someday, they ever got the chance to visit Omaha beach and the cemetery that was going to be built there, would they put some flowers on the graves of a few friends he had left behind. They said they would, and so, seven years later, they took a bus from Paris to put flowers on American graves, not because they remembered history and the Liberation, but because they remembered coffee, food and human kindness.

THEODORE H. WHITE

Things all go past and they fade away

After each December there comes another May.

POPULAR GERMAN SONG, 1942

Prologue

SEPTEMBER 2001

On the lower tip of the island of Manhattan, fires trapped deep beneath the twisted metal girders were still burning. In great cities around the globe, people gathered to express their outrage and their sympathy. Hundreds of Londoners stood in silence when Big Ben rang at noon. When the guard changed at Buckingham Palace, the band played a song about the American flag still waving after a failed British assault on Fort McHenry. In Beijing and Amman, bouquets and wreaths piled high at the gates of the American embassies. In Dublin, the stores closed in commemoration. Children in the West Bank held candlelight vigils. In Paris, the newspaper headline was We Are All Americans.

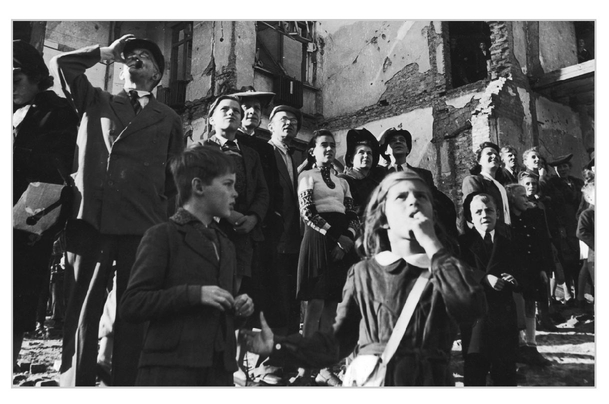

But nowhere was there a greater outpouring of humanity and emotion than in the German capital of Berlin. There, 200,000 people gathered along the broad avenue leading through the Tiergarten to the Brandenburg Gate. No one was quite sure why so many turned out.

The crowd felt young. Men and women in their twenties wore backpacks and shorts under the late summer sun; parents pushed strollers and held children by the hand in the enormous throng.

One woman stood still, alone in the crowd, lost in her thoughts as families and couples marched past her. She was old and stooped. Her hair waswild and she wore a dark, heavy coat even on the warm day. She was quietly sobbing.

Two young men approached her and asked why she was crying. She seemed startled, as if roused from a slumber. I love Americans, she said quickly, in a way that was so imploring they understand that it grabbed them and shook them by their lapels. She started to go on, to say more, to explain, but before the words came out, her gaze widened and warmed, the tears replaced by an ineffable joy. Her shoulders straightened just a bit. The wrinkles seemed to flee her face.

A distant, happy memory danced across her eyes as she looked upward, toward the sky. She began softly, in a whisper. You see, I was a girl during the Airlift....

Introduction

JUNE 24, 1948

Years later, long after the bunting and banners had been torn down, delegates to the 1948 Republican convention would fondly remember the busty blonde in the rowboat. It was Wednesday night, June 23, 1948, and the floor in Philadelphia was open for nominations. For the first time in twenty years, a convention was meeting with neither economic depression nor global war as a backdrop. Instead, Americansin those bursting, jubilant years after the end of World War IIwere living in a period of plenty and progress that would have been unimaginable only a few years before.

Outside the convention hall, Philadelphia was hot and humid. After only a few moments of walking about, the delegates felt as if a heavy velvet had been draped over their skin. But they rushed between the various candidates headquarters in a mood of delirious excitement. Harold Stassen, the young former governor of Minnesota who was the favorite of Republican voters across the country, handed out red-white-and-blue buttons and 1,200 pounds of cheese. Robert A. Taft, the grandson of an attorney general and son of a president and chief justice of the Supreme Court, passed out buttons in the shape of a four-leaf clover. With a pained expression, the favorite of conservatives acceded to his advisers request and shook hands for the cameras with a baby elephant named Little Eva. The pachyderm was draped with a blanket on which was written Renounce Obstinate Bureaucracy, End Roguish Tactics, And Tally Americanism, Freedom, Truth, a catchy slogan whose acronym just happened to be Robert A. Taft. Over at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, New York governor Thomas E. Dewey put them all to shame. His campaign gave away cigarette holders, ashtrays, and matchbooks; lipstick, luggage, and lingerie; unlimited bottles of pop provided by the president of Pepsi-Cola; chewing gum, boxes of chocolate, and 5,000 rolls of Life Savers. Thus, of course, Dewey was the conventions front-runner.

The air of abundance was evident on the convention floor, where two marching bands, Scottish bagpipers, and men with megaphones all competed for attention. The statuesque sailor in the eye-popping outfit, there on behalf of Stassen, moved through the sea of delegates atop a float, greeted with chants of Man the Oars and Ride the Crest, Harold StassenHes the Best. To Steer Our Craft, Lets Take Taft, came the shouted answer. To make the speakers voices heard above the commotion, the arena installed what H. L. Mencken called a loud-speaker system that is to any loud-speaker system of the past as the range of Himalayas is to a crabcake. For weeks leading up to the convention, newspapers and magazines had carried ads for television sets that read Meet Your Next President on RCA Victor. The new phenomenon of television carried the proceedings from gavel to gavel since it was an inexpensive way to fill airtime. Ten million people, including President Harry S Truman sitting in front of a television in the White House, watched the conventionmore than had witnessed every previous political convention in America combined. It was then the largest television audience in history.

The Republican convention had a plethora of seemingly everything, but what it had mostand this fairly oozed from the delegateswas confidence. The Democratic Party had been split by the issue of relations with the Soviet Union, resulting in what the New York Times chief political correspondent described as the countrys general conviction that the nominee of the convention will become the next president of the U.S.

But in the pivotal year of 1948, it was not the campaign of Thomas Dewey to capture the White House that would dominate the newspaper headlines. Another event would seize the publics attention and ultimately deny Dewey his victory. It was the battle for Berlin.

IT WAS 4 A.M. in Philadelphia, almost dawn, when the convention adjourned and the delegates stumbled bleary-eyed into bed, not realizing that while they had been in the hall a global crisis had arisen that threatened to spark World War III. Berlin, a city divided up between the victors of the last world war, lay deep within the Soviet-occupied parts of Germany. At 6 A.M. there on June 24, 1948, as the cheers for Taft were dying down in Philadelphia, the Russians, in order to capture control of the entire city, halted the trains, trucks, and barges that brought food, coal, and every other supply into the western portions of the capital on a daily basis. Two and a quarter million people in Berlinthe biggest city in the worldwere cut off from everything they needed to survive.