Concise History of the Modern World

Covering the major regions of the world, each history in this series provides a vigorous interpretation of its regions past in the modern age. Informed by the latest scholarship, but assuming no prior knowledge, each author presents developments within a clear analytic framework. Unusually, the histories acknowledge the limitations of their own generalizations. Authors are encouraged to balance perspectives from the broad historical landscape with discussion of particular features of the past that may or may not conform to the larger impression. The aim is to provide a lively explanation of the transformations of the modern period and the interplay between long-term change and defining moments of history.

Published

A History of Modern Latin America

Teresa A. Meade

A History of Modern Africa, second edition

Richard J. Reid

A History of Modern Europe

Albert S. Lindemann

This edition first published 2013

2013 Albert S. Lindemann

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwells publishing program has been merged with Wileys global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell .

The right of Albert S. Lindemann to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available upon request.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

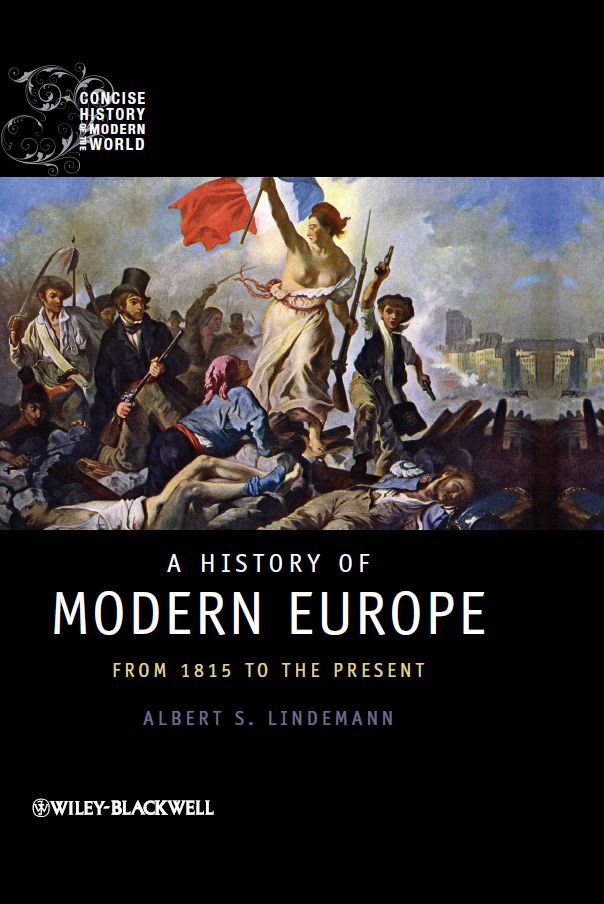

Cover image: Liberty leading the People, 19th century print after Delacroixs 1830 painting.

Ivy Close Images / Alamy

Cover design by www.simonlevyassociates.co.uk

Preface

The Dilemmas and Rewards of a Concise Historical Overview

Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it.

(attributed to George Santayana)

We Communists have no difficulty in predicting the future its the past that keeps changing on us!

(anonymous)

Memory is like a crazy old woman, storing colored rags and throwing away good food.

(attributed to Austin OMalley)

In the nineteenth century, Europeans produced a dazzling civilization, a culmination of centuries that was once termed the rise of the west. Europe influenced the rest of the world to an extent that few, if any, previous civilizations had. Europeans were admired and imitated but also feared and hated in much of the rest of that world. The empires of individual European countries, especially those of Britain and France, ruled over hundreds of millions of non-European peoples, often with a heavy hand. Europeans came to believe in their inherent superiority to other peoples, and there was no denying the Europeans scientific discoveries, military power, and all-round creativity. Yet, driven by the demons of the extreme left and right, European civilization nearly committed suicide, pulling much of the rest of the globe into two massive conflicts termed world wars, resulting in the deaths of tens of millions and incalculable miseries for millions more.

A familiarity with that history is obviously desirable for any educated person in the early twenty-first century, but such a familiarity is not easily gained. The volumes of Wiley-Blackwells Concise History of the Modern World series are designed for readers with no prior knowledge of the topics covered, but those volumes also have the goal of offering vigorous interpretation and insights from the latest scholarship. Any presentation of modern European history with those requirements must pay especially rigorous attention to priorities, leaving out much that would find a place in a longer volume for a different audience. In particular, any history intent on presenting penetrating analysis and provocative interpretive perspectives must be substantially different from an inclusive, fact-filled, chronological narrative. At any rate, most modern historians have long since moved away from presenting just the facts in an objective way. Professional historians see their discipline as question-driven, involving debate and ambiguity, rather than simply one in which facts are accurately, amply, and objectively presented. Again, the professional historians approach to history involves priorities, unavoidably stirring up debate about the nature of those priorities.

The above three epigrams suggest many of the challenges and pitfalls associated with writing an overview that is readable and yet avoids condescension. The first quotation is the most widely familiar. Attributed to George Santayana, it is a simplification of his actual words (Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to fulfill it); the following pages will have much to say about the lessons of history lessons that have often turned out to be simplistic and misleading, if not utterly false, leading to new tragedies. The second quotation, while obviously tongue-in-cheek, makes a point about the past that is tacitly accepted by all historians not that historical facts can be crudely ignored, as was notoriously the case under Communist rule, but rather that what interests us about the past subtly evolves. We are constantly discovering new details about the past, and partly because of that new information we continually reformulate the questions we ask about that past. This is not to assert that the past itself changes; it is rather to recognize that we look for new things, while losing interest in things that had once fascinated us.

The third of the above quotations observes how our memory tends to be attracted to the gaudy and garish, passing over good food in other words, avoiding more valuable memories, especially if they are awkward ones. That quotation also touches on one of the major issues for those writing modern history: the widening gap between popular history and history written by professional historians, the first colorful and highly readable but also tending to be conceptually shallow, the second generally less readable but more intellectually challenging. That division has a convoluted relationship with what have been termed the old and new approaches to the writing of history. A venerable or old tradition in history-writing concerned itself primarily with the role of great men and with those areas in which such men predominated (politics, diplomacy, and warfare, but also scientific inquiry and economic enterprise, to name just a few). New history has its own honored tradition in its concern to revise or radically reconceptualize how we understand the past, to achieve fresh perspectives on it and is especially proud in announcing its move away from the earlier focus on great men.

Next page