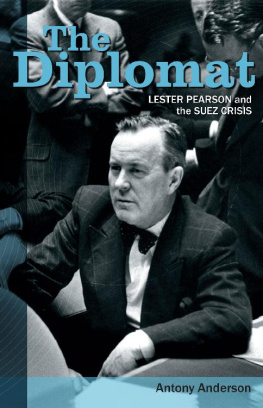

CHAPTER ONE

The Making of Mike

A little surprise awaits visitors by the back stairs on the second floor of Laurier House in Ottawa. In the Second Empire home of Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Mackenzie King, now a national historic site, they discover a small shrine to Lester Bowles Pearson. The strange thing is that Pearson never lived here. After his death, the archivists suggested there was room for another Liberal prime minister in Laurier House and asked the family for some of his mementoes. They used these to turn the servants quarters into a replica of the study Pearson used in retirement. We agreed that these things were part of Canadian history and the public should be able to see them, said Maryon Pearson, his widow, when she opened the study in 1974. It was to remain at Laurier House until a permanent home could be found. None was, and the exhibition is still here.

It helped that Pearson lived in a time of gifts rather than gift cards. Words were etched on silver rather than sent into cyberspace. It also helped that this homme du monde who had been everywhere seemed to keep everythingbowls, plaques, trophies, cups, medals, ribbons, photographs, cartoons, ceremonial keys, baseball bats, lacrosse rackets, even his diplomatic gold braid and blue uniform and the red-and-white robes he wore receiving one of his forty-nine honorary degrees. In the centre of the room is his unadorned desk and swivel chair from the basement of 541 Montagu Place in Rockcliffe Park, where he moved in 1968. Pearsons study has none of the solemnity of Kings sanctum sanctorum on the floor above. No panelled Georgian library of pedestals, portraits, tapestries, leather wingback chairs, and crystal decanters here. This is Mikes Place: a sofa with throws, a wooden rocking chair, a metal globe, and a hand-hooked woven carpet in the design of the flag of Canada. The fraying, faux red brick is falling away in places. Behind the desk hangs a painting of the church in southern Ontario where Pearsons father was pastor and an outsize aerial photograph of Expo 67. With a walnut-veneer television console and an orange shag carpet, this could be a man-cave in any suburban bungalow, circa 1972.

Here are hints of the mans character: modesty, simplicity, curiosity, ambition. Here are the entrails of his experience in school, sports, the academy, diplomacy, government. What we dont know, a wall of photographs shows us: Pearson as a baby in 1899, as a groom at his double wedding in 1925, as a grandfather with his brood in 1964. Pearson as statesman at the General Assembly; Pearson as Nobel Laureate in Oslo; Pearson as newly elected leader at the 1958 Liberal Party National Convention. Pearson with Sir Winston Churchill, Nikita Khrushchev, Louis St. Laurent, Dwight Eisenhower, Queen Elizabeth, and so many others.

Best wishes from John F. Kennedy (with appreciation for a fruitful visit), who greeted him warmly at Cape Cod in 1963, relieved he wasnt John Diefenbaker. From Secretary of State Dean Acheson (to Mike and Maryon, with esteem and affection founded in many years of friendship and work and play together? [ sic ]), who would have less esteem for this moralizing Canadians views on Korea in 1951. From Lyndon Johnson (with very high regards), which were less high when Pearson spoke out on Vietnam in 1965. From Charles de Gaulle (very cordially from your loyal friend of Canada), who was neither friendly nor loyal when he visited Montreal in 1967.

Tucked away in this dim, airless mansion of death masks, Ouija boards, crystal balls, and the echo of seances, where Laurier moved the year Pearson was born and where King lived until his death in 1950, visitors find the talismans and tokens of a dazzling seventy-five years. I have been fortunate in all my lives, Pearson said as they were beginning to run out. Ive had almost as many as a cat. Those lives took him from the parsonages of small-town Ontario to the battlefields of Europe. They led him to Toronto, Chicago, and Oxford to study and work, to London, Geneva, Washington, and New York to addressand sometimes resolvethe vexing issues of his time. And then back home, to Ottawa and a long, fitful stewardship in politics, first in opposition, then in government, leading the country, making his mark. When he died in 1972, his body lay in state. A nation mourned. They buried him on a hilltop in a cold rain.

For all that, Lester Pearson is known only vaguely to Canadians today. Scores of schools, an international college, and the countrys busiest airport may bear his name, but polls suggest that Canadians dont really know why. They may have a gauzy, faint notion of him as an angel of peace. That he fought in the Great War and represented Canada at the League of Nations and the United Nations, that he was the best-known Canadian in the world of his time, that he rebuilt the Liberal Party and led it back to power, that he governed Canada for five feverish yearsof all this, they know little. That he developed peacekeeping, created the flag, enacted health care, and introduced bilingualismall of which have come to define contemporary Canadaof that they may know even less, if anything at all.

For its own odd, inexplicable reasons, Laurier House does not publicize that Lester Pearson lives on its second floor. In a museum devoted exclusively to the memory of Laurier and King, he is seen as an interloper; there is no mention of him or his study anywhere (not on its signs, not in its literature, printed or electronic). It is as if he is here illegitimately, a squatter under the eaves who has overstayed his welcome, an embarrassment and a secret.

Fortunately, by now, his story is out.

AT THE BEGINNING , who could have known how it would end? The world in which Lester Bowles Pearson arrived on April 23, 1897, was thoroughly unlike the one he left three-quarters of a century later. God was in His heaven and Queen Victoria on her throne, he wrote in Mike , the first of his three-volume memoir, published in 1972. All was well. The Empire, on which a sun never dared to set, was being made mightier yet; Canada was about to enter the century that belonged to her. The year of his birth marked the Diamond Jubilee of Britains longest-serving monarch, presiding over the greatest empire the world had ever known. There may have been rebellion in India and unrest in the Transvaal, but all was peaceful in Canada thirty years after Confederation. At the turn of the century, Canada was largely rural, conservative, white, Christian, and British. It had no national flag, no foreign ministry, no citizenship or other symbols of nationhood that would become the motifs of Pearsons thrusting generation. At the same time, a patriot could believe that the new century would belong to Canada, as Sir Wilfrid Laurier would muse in 1904. Although Canada had few people, it did have land, resources, and freedom. As we know, the century would turn out differently for Great Britain and Canada. While the British Empire would collapse, Canada would become a country in more than name. Burdened by its own peculiar pathologies, though, Canada would not own the century. In fact, after a near-death experience over Quebec in 1995, it was happy to survive it.

Pearson was born in Newtonbrook, a hamlet on Yonge Street, north of Toronto, on St. Georges Day. His mothers forebears were the Bowles, who came to Canada from Ireland in the 1830s. His maternal grandfather, Thomas Bowles, was a Methodist preacher who served as reeve of his township. He ran twice provincially and once federally for the Liberal Party, narrowly losing each time. Pearsons maternal grandmother, Jane Lester, enchanted her young grandson. Despite the age difference of seventy years, there was an intimacy between them. His other grandparents were part Irish. The Pearsons were Tories and the Bowles were Liberals, each aggressively so.