Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by C. Robert Ullrich and Victoria A. Ullrich

All rights reserved

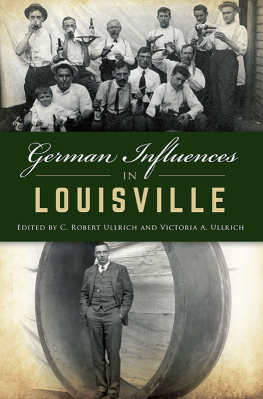

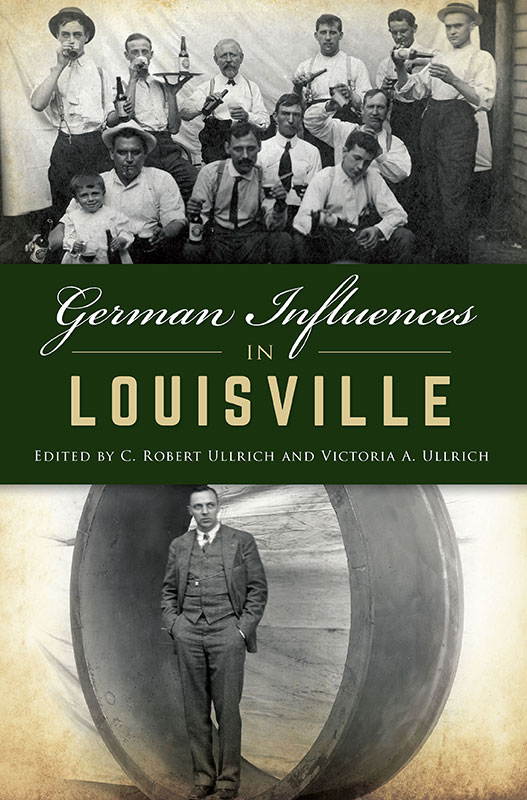

Front cover, top: Courtesy C. Robert Ullrich and Victoria A. Ullrich.

Front cover, bottom: Courtesy Lewis A. Meyer.

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.792.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944029

print edition ISBN 978.1.467144.070

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

In memory of Martha Elson.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

To leave behind ones homeland, family, friends and culture is a difficult decision. Then, to travel on a perilous journey across a vast ocean and start life anew in a foreign land certainly must be a stressful situation. This is what thousands of German immigrants did in the nineteenth century. Enduring this anxiety-filled experience resulted in many achieving their hopes of a brighter future.

My German ancestor, John Jacob Wiser, stowed away on a ship at age twelve. He settled in southwest Jefferson County, married Luzanna Arnold, had nine children and owned a four-hundred-acre farm. Johns life paralleled those of many other Germans whose fortitude and hard work resulted in a prosperous existence for them and their many descendants.

From construction workers, carriage makers and blacksmiths, to jewelers, photographers, artists and musicians, among many other skilled craftsmen, Germans built a successful society in Louisvillefar away from their native country. No matter where one goes in our city, there is most likely a German connection to that location. In neighborhoods like Germantown and Butchertown, as well as in numerous churches, schools, medical services and businesses, there are references to German immigrants who helped those places to be established and flourish.

This book celebrates all these men and women of German heritage who overcame the challenges and established new lives in Louisville. It documents their legacy of meaningful contributions. There are very few books about the German influences on our city, and this book greatly expands on this understanding.

Louisville greatly benefited from the knowledge and determination of German immigrants to create a community that is now one of the best places to live in America.

Stephen A. Wiser, President Louisville Historical League

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The editors would like to thank everyone who contributed to this book, especially the chapter authors. Also, we would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of John E. Kleber and Mary Jean Kinsman, who served as manuscript editors.

Special thanks are due to Reverend R. Dale Cieslik of the Archdiocese of Louisville Archives for his generous help as well as the University of Louisville Photographic Archives and the Filson Historical Society for the use of their collections. Finally, the editors would like to thank the many individuals who contributed photographs from their personal collections for use in this book.

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

BY C. ROBERT ULLRICH AND VICTORIA A. ULLRICH

Although Pennsylvania Dutch settlers lived in Louisville as early as the 1780s, the first German-born immigrant to arrive here was August David Ehrich, a master shoemaker from Knigsberg, Prussia, who came in 1817. The first Louisville city directory, published in 1832, included Ehrich and twenty-four other German-born heads of household, including John Schmidt and Emanuel Seebold, who emigrated in 1819.

In contrast to the small number of Germans living in Louisville in 1832, the German immigrant population of Louisville in 1840 was at least four thousand, and the neighborhood east of the city center, known as Uptown, was completely populated by Germans. Similar dramatic increases in the German populations of Cincinnati and St. Louis occurred in this same time period. There are two main reasons for this.

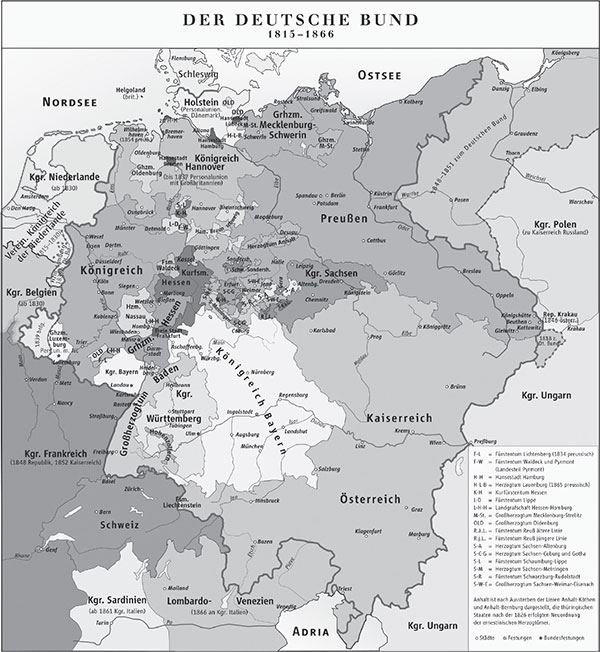

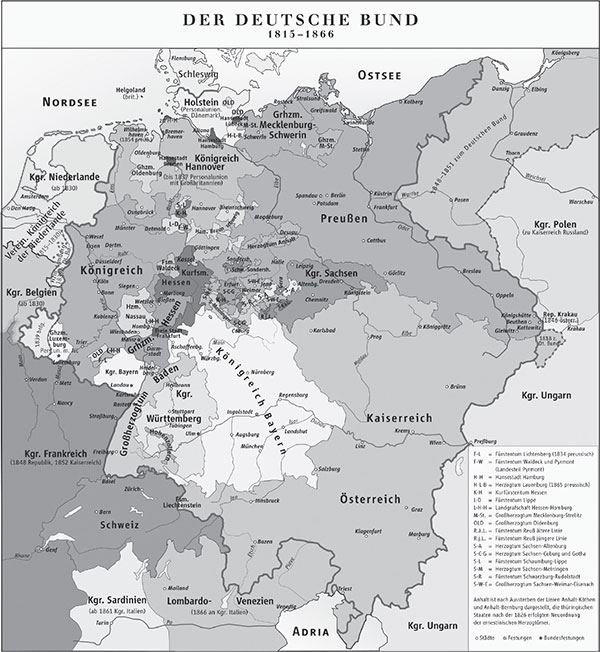

First, following the Napoleonic Wars (180315), the Congress of Vienna established the German Confederation, a loose association of 39 kingdoms, duchies, principalities and free states. While the Confederation was essentially the same alignment of states that existed before the wars, most Germans had hoped for national unity instead. By the 1830s, the lack of a coherent economy in the German states, coupled with political unrest, led to disillusionment. Many Germans seeking new opportunities saw the United States as an enticement. Unrest in the German states continued through the 1840s, culminating with the 1848 Revolution, which also failed to unify Germany and led to another wave of immigration to the United States. The wave of immigrants that came to the United States in the 1830s, known as the Dreissigers or Thirtiers, numbered as many as all of the Germans who had come in the colonial period. Whereas only 5,753 Germans immigrated to the United States in the 1820s, 124,726 came in the 1830s and 385,434 came in the 1840s.

The German Confederation, 181566. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

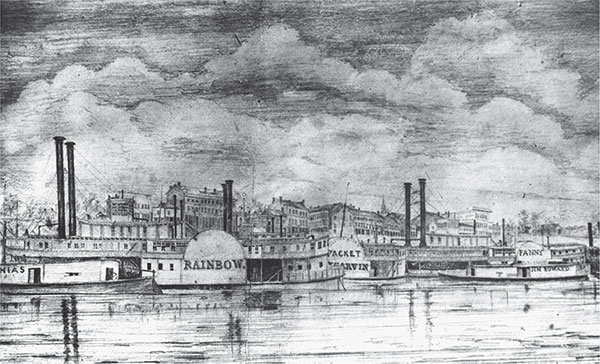

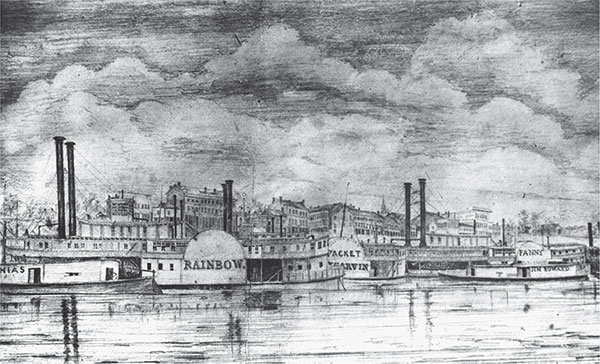

Second, Robert Fultons New Orleans, built in Pittsburgh in 1811, was the first steamboat on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Very few steamboats were built to operate on the Ohio River before 1820 but by 1834, 304 had been built in Pittsburgh, 221 in Cincinnati and Covington and 103 in Louisville and Jeffersonville. The advent of the steamboat coincided with the first significant wave of German immigrants to arrive in the United States, and it enabled immigrants to move from ports of arrival in the East to the interior of the country via the inland waterway system. As a result, cities along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, such as Evansville, Louisville, Cincinnati and St. Louis, experienced a significant influx of German immigrants in the 1830s.

One reason that immigrants chose Louisville was the Falls of the Ohio River. Prior to the construction of the Louisville and Portland Canal in 1830, boats traveling upstream unloaded passengers and cargo at the Portland Wharf, located several miles northwest of Louisville. Anyone wishing to continue traveling upstream would journey on land to Louisville and board another boat at the Louisville Wharf. Of course, the reverse was true for passengers traveling downstream. Many immigrant passengers simply stayed in Louisville rather than traveling on. Even after the canal had been built, both Portland and Louisville remained important stops for travelers along the Ohio River, and many immigrants disembarked at the Falls and settled in Louisville.

In German immigrant enclaves along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, many immigrants wrote letters home, encouraging others to join them in America. And they did. From 1850 through World War I, 5 million German immigrants came to America, with 1.5 million of them arriving in the 1880s. Nearly 7.5 million Germans immigrated to the United States from 1820 through 2010by far the largest number of any nationality.

Next page