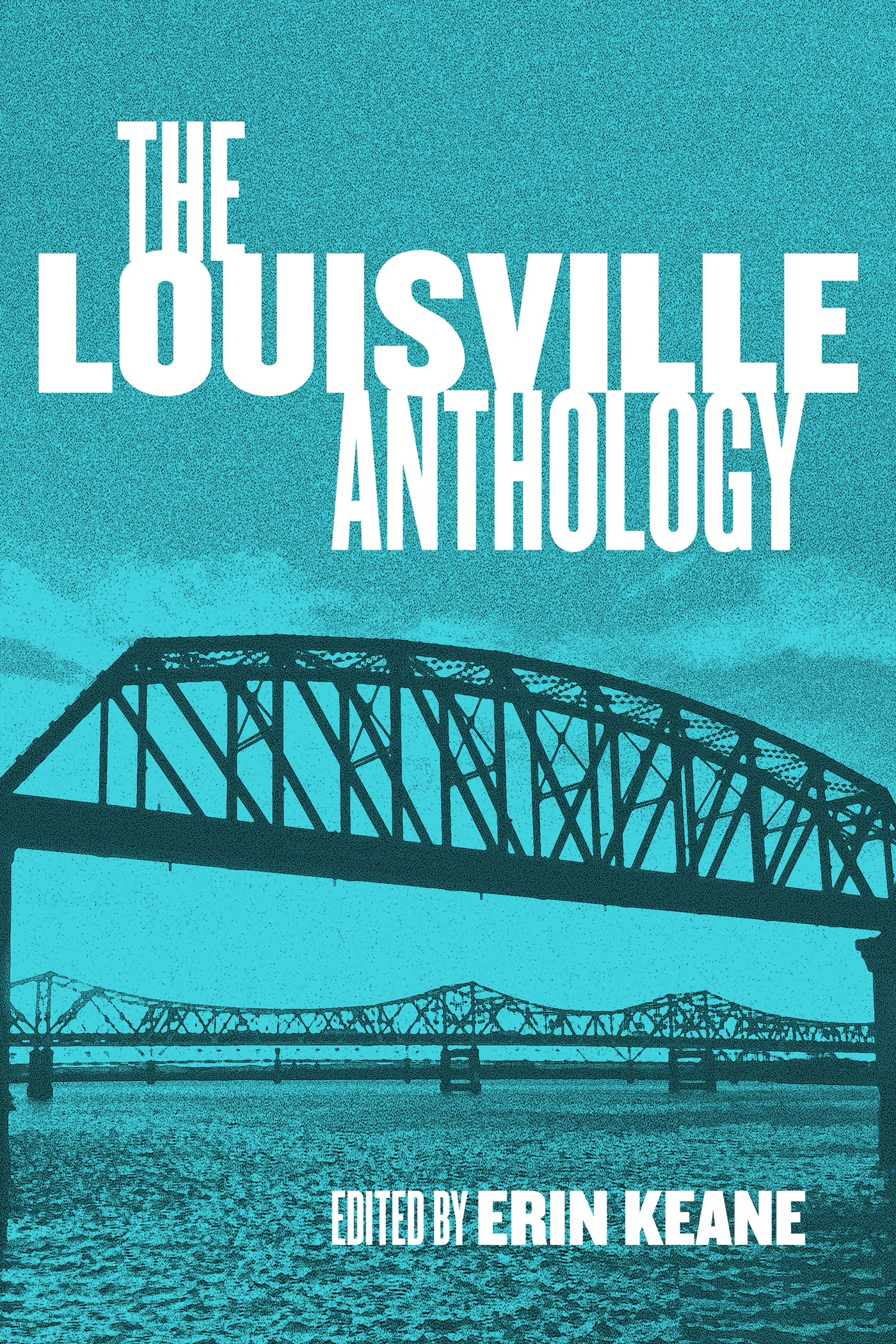

THE

LOUISVILLE

ANTHOLOGY

THE

LOUISVILLE

ANTHOLOGY

EDITED BY ERIN KEANE

Belt Publishing

Copyright 2020, Belt Publishing

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

First Edition 2020

ISBN: 9781948742702

Belt Publishing

3143 W. 33rd Street, Cleveland, Ohio 44109

www.beltpublishing.com

Book design by Meredith Pangrace

Cover by David Wilson

CONTENTS

Erin Keane

Emma Aprile

Richard Becker

Ellen Birkett Morris

Brenda Yates

Ben Gierhart

Derek Mong

Andrew Villegas

Andrew Villegas

Asha L. French

Idris Goodwin

Martha Greenwald

Amy J. Lueck and David James Keaton

Almah LaVon Rice

Kathleen Driskell

Patrick Wensink

Dana McMahan

Nancy McCabe

Michael L. Jones

Tim Harris, Tara Key, and James Nold, Jr.

Brett Eugene Ralph

Brett Eugene Ralph

Dan Canon

Joy Priest

Joy Priest

Joy Priest

Joy Priest

Joy Priest

Gwen Niekamp

Aaron Rosenblum

David Serchuk

Svetlana Binshtok

Kimberly Garts Crum

Beth Newberry

Ashlie D. Stevens

Fred Schloemer, with Susan E. Lindsey

Ashlee Clark

Caleb Brooks

David Harrity

Norman BuzzMinnick

Olga-Maria Cruz

Steven Carr

Introduction: A Letter from the Borderlands

ERIN KEANE

After living in Louisville for more than twenty-five years, Ive learned that one of the fastest ways to start an argument here is to ask any group of peoplelocals, newcomers, curious bystanders alikeif this is the southernmost midwestern city or the northernmost southern town. Some declare with certainty that Kentuckys borders define it as southern by default, while others argue that Louisvilles position on the Ohio River gives the city more kinship with its immediate neighbors in Indiana than with the Commonwealth as a whole. This shouldnt come as a surprise. Borderlands tend to defy easy characterizations. But the arguments on both sides reveal much about how Louisville straddles two worlds, and how the city does and does not reconcile its contradictions.

Louisville has a story it likes to tell itselfthat being from Louisville, not Kentucky is a possibility, a point of pride even for some. Invoking Lyman T. Johnsons bifurcated view of the city never goes out of style, it seems: I break Kentucky into two parts, Louisville and the rest of the state, Dr. Johnson, a prominent twentieth-century African-American educator, famously said. Louisville is oriented to the North, culturally and commercially. The rest of Kentucky looks to the South.

Somewhat less popular is this assessment, made by Omer Carmichael and Weldon James in The Louisville Story, a book about desegregating the public schools in the 1950s: Louisville, like Kentucky, seceded after Appomattox.

Of course, both things can be true at once. That doesnt make it any less ironic when the occasional not-quite-tongue-in-cheek calls for Louisville to secede from Kentucky bubble up, in hopes of forming an independent urban fortress where discerning denizens claim only the marketable products of the statebluegrass music, bourbon, biscuitswith the surrounding countryside relegated to a sort of storage closet for the destructive policies, histories, and attitudes the city wishes for its visitors not to see.

Here I have to confess: I am not from Louisville. If I said this to a person hailing from anywhere else they would be right to be confused. After all, I have taught classes and worked in offices and written books and danced to bands and fallen in and out of love here; learned how to drive, how to grow tomatoes, how to put two dollars across the board on the long shot, how to drink bourbonand, crucially, how to know when to stopall right here in this pocket of the Ohio River Valley, where a chenille blanket of pollen drifts over our heads a full ten months out of the year, for a quarter of a century now and counting, and surely that makes it official. But to be from here, as I learned at seventeen when I moved into a residence hall on the Bellarmine College campus in the Belknap neighborhood of the Highlands, is to be able to claim roots that run deeper than a college ID and the inevitability of committing the Twig & Leafs twenty-four-hour diner menu to heart.

In shallow terms, I have neither high school allegiance nor home parish. My opinions on college basketball are weak. I have missed crucial events that imprinted on my generationNational Guard soldiers overseeing the busing program to fully desegregate the public schools, the tragic Standard Gravure shooting, the sewers blowing, certain local bands playing live who have since passed into legend. I lived here for at least eight years before I finally learned where the old Sears building, a weirdly specific navigational lodestar, had once been. And to this outsider at least, the part of Louisville that wants to be recognized as culturally different from the small towns around itfacing outward and upward, always moving in the direction of progressseems forever at odds with the part of Louisville that struggles with contextualizing those who were not raised by its specific local ghosts.

Live in a city caught between onward and remember-when long enough, though, and you develop a personal palimpsest map almost in spite of yourself: Lets meet at the new place that used to be the other place that moved in after Flabbys, the Schnitzelburg bar with the legendary fried chicken, where the burn of an oyster shooters hot sauce christened one of my most important apartment moves.

A sign hanging outside a Newburg Road restaurant known, despite all past or future name changes, as Kaelins, encourages passersby: If you cant stop, please wave. The Highlands institution has long claimed to be the birthplace of the cheeseburger, invented there in 1934 by founder Carl Kaelin. Periodically, the veracity of this claim comes under review, and the conclusion is usually a variation on, So they say. We may not always share an undisputed truth of a place, the Kaelins sign suggests, but we can acknowledge our myths and legends and accept them on their own terms.

I may not be from Louisville, but I have spent a quarter of a century learning about it, starting with a college friend pointing out how close we lived to Daisys house from F. Scott Fitzgeralds The Great Gatsby, after an afternoon of coffee and browsing at Twice-Told Books on Bardstown Road. Daisy Buchanan the It Girl had been unmarried Daisy Fay when a poor soldier, Jay Gatsby, courted her during a brief stint at Louisvilles Camp Taylor, where Gatsbylike Fitzgerald himselfhad trained during the first World War. Fitzgerald describes Gatsby and Daisy sitting on her porch and taking romantic walks in a Louisville neighborhood that on the page sounds very much like the Cherokee Triangle. But the longer I lived in Louisville the more I learned about the distance between what we want to believe and what we can prove. Several houses are in fact believed, separately, to have been the true Daisy homethe Moonie house, the Hilliard House, the old Emma Longest Moore home, each the designated pinnacle of twinkle-lit wealth, careless comfort, and doomed beauty in someones yearning heartand on each of those porches it is equally possible, on a warm spring evening, to glimpse from the sidewalks safe distance a flash of streetlight reflecting off an unseen diamond. And if the true model for Daisys home is now believed to have been a house outside of Chicago where another rich girl lived once upon a time, so what? This combination of wishcasting and hustle is how we know Gatsbys unobtainable Daisy, that apparition who manages to be both southern and midwestern at once, must be at home here after all.

Next page