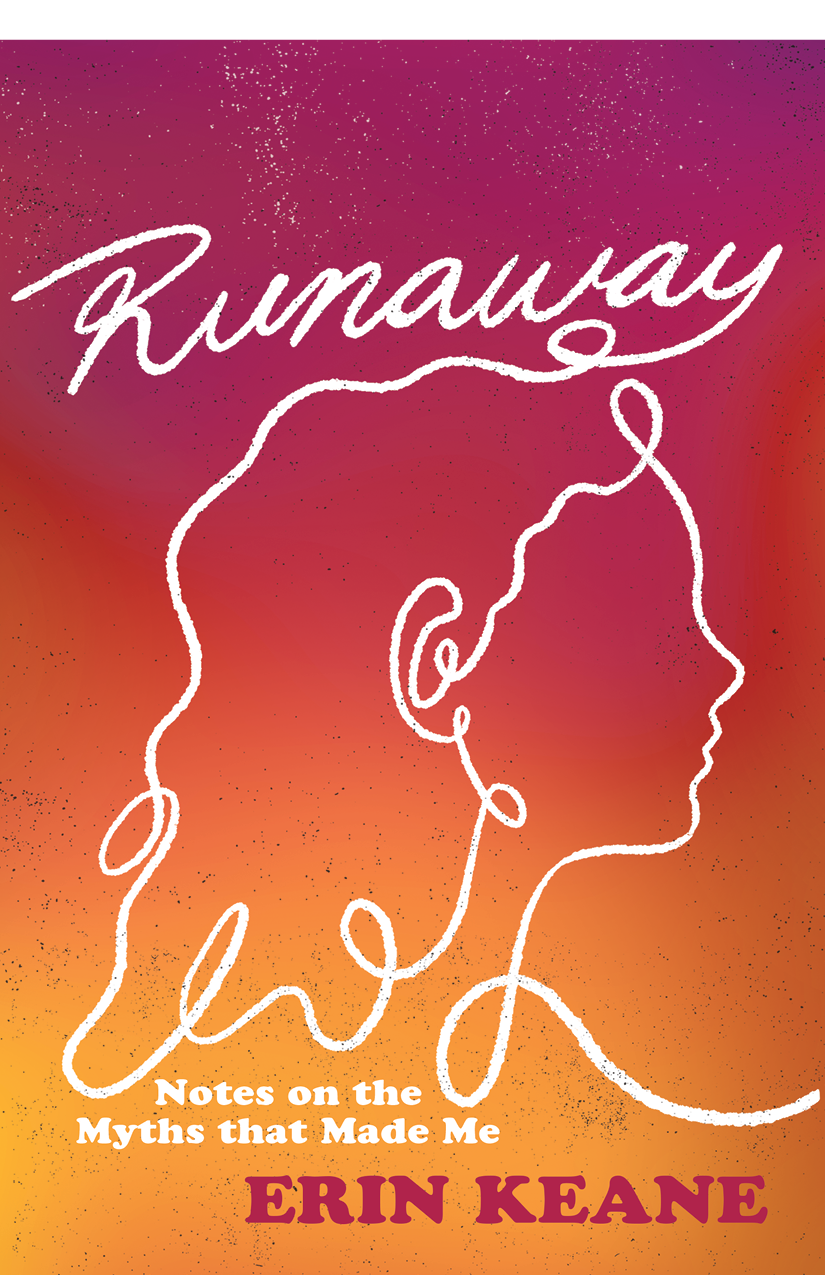

Copyright 2022 by Erin Keane

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief

quotations in a book review.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition 2022

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-953368-32-4

Belt Publishing

5322 Fleet Avenue

Cleveland, Ohio 44105

www.beltpublishing.com

Cover art by David Wilson

Book design by Meredith Pangrace

Authors Note:

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names have been changed and are so noted in the text. Some personal details have also been obscured to protect privacy. Conversations, scenes, and situations have been recreated and dramatized using the best recollection of interview subjects, and supported, when possible, with media accounts, public information, and other research.

For my mother and my brother,

and for Megan and Alexis.

1

Shes a Bright Girl

Of all the lies I once believed about my mother and father, the biggest was the one I told myself. For most of my life, I reveled in my origin story as a daughter of the grittier, downtown version of Woody Allens Manhattan , a movie I loved fiercely, perhaps because it too demanded a certain amount of self-deception. In 1972, my mother was fifteen years olda beautiful runaway from a respected military family, living as an adult under a fake name in New Yorks East Villagewhen she met my father at Googies, her favorite bar. They fell in love and married that year. He was a recovering heroin addict, sporadically employed and with a criminal past, a self-taught, bullshitting Renaissance man who drove a cab and wooed her with barstool poems. He was also the same age as her father.

Googies is where I thought my familys story started, when he was thirty-six and nobody knewor more likely, nobody caredthat my mother was a child, claiming to be in her twenties with a name and a backstory that had nothing to do with being the daughter of an Army officer and a mother in bespoke beaded dresses who saw cotillion and college in her daughters future, not hitchhiking across the country, sleeping in subway stations, hanging around bars with penniless actors and artists, drinking for cheap. After all, in Manhattan , we dont see what seventeen-year-old Tracy was doing before she starts dating Isaac, the twice-divorced protagonist who is her fathers age and who cracks self-conscious jokes about it in front of his friends. Were not actually supposed to care. A girl becomes visible to the world, stories like Manhattan taught me, when a man appears next to her in the frame.

It is embarrassing now to admit how much I believed in Manhattan and for how long it remained one of my favorite films. And yet I know Im not alone. A movie doesnt become a perennial best-of without a certain cultural consensus behind it. (See the 2007 critical outcry from New York magazine after the doddering American Film Institute dropped Manhattan from their Best 100 Films list. The magazine protested that the movie is an absolutely perfect film, one of the few that, a hundred, two hundred years from now, theyll still be watching, list or not. Call me impressionable, but 2007 was the year I started my own career as a culture writer, and I gave a lot of weight to what New York s critics wrote.) That same consensus has long positioned mens narratives as the worlds de facto serious stories, even when the fictions they contained were wildly self-indulgent. After Allens adopted daughter Dylan refused to stay silent as an adult about her allegations that he molested her when she was a child, the cultural consensus now about Woody Allen is, to quote actor Wallace Shawns defense of him, that he is a pariah. As a supporter of survivors of abuse and exploitation, I have no appetite for his work anymore. But I cant pretend I never did. If you had asked me ten years ago if I thought there was anything wrong with the relationship Allen wrote for his stand-in Isaac and the teenaged Tracy, a role that garnered Mariel Hemingway an Academy Award nomination, I would have waved away the question with a noncommittal shrug. To make great art, we must create space and empathy for characters who make bad choices, right? And that grace we extend to fiction has long bled over to include the arts makers and their misdeeds.

At long last, thats beginning to change. Prominent men in numerous industries have been exposed, denounced, and diminished over their exploitations of power, including with teenage girls. Headlines treat those men as powerful outliers. But I dont believe theyre special. Their choices were formed by a culture that romanticizes men who have big appetites that shape their allure and cause their downfall, all while casting aside the unruly girls left in their wake as damaged goods.

I am also of that culture, a product shaped by it. My father, the complicated seeker; my mother, his beautiful life raft. I never questioned their marriages power imbalance, how it tilted everything in his favor. He died when I was five, which transformed him into a romantic figure in absentiaa fantasy, a celebrity of sorts, intimately knowable and shrouded in mystery all at once. My mother outlived him, moved on from his death, and built a new life for herself and us. But I remained loyal to him in the most childlike way, nurturing the hole his absence left in me, tending its jagged borders as a memorial to his tragic ruin. Flawed male protagonists and their dissolute creators, self-destructing musicians with sordid reputationsI welcomed them into that space. I craved their voices because I couldnt hear his.

On their first date, my father took my mother to a seafood restaurant on Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village that I think must have been the original Captains Table. Red, as he was called because of his ginger hair and beard, was tall, barrel chested, and blue eyed. As he steered her toward their table, he leaned over to murmur in her ear, Mafioso hang out here. My mother believed him. He had a way of saying things that made them sound true. She had wide green eyes, high cheekbones, fair skin, and long dark hair that hung straight down the middle of her back. She could two-finger whistle a cab down from a block away. That night, she was wearing her favorite dressa halter-top maxi, midnight blue swirled with purple clouds and moonsand platform sandals that made her taller than five-nine. At this point, my father still believed she was twenty-four years old and that her name was Alexisboth lies. She had heard hints of his past too. Only some of them turned out to be true. As they ate and talked, a cop in street clothes approached their table, with its bottle of wine and two glasses, flashed his badge, and asked to see her ID.

I left my purse at home, she lied without hesitation.

The cop stared, unimpressed. Clearly, he suspected she was too young to be drinking on a date with this man who was old enough to be her parent. He must have noticed they werent acting like father and daughter. Maybe he was part of the NYPDs recently formed Runaway Unit, tasked with keeping an eye out for minors who werent supposed to be living on their own, grilling them for identification, and arresting them if their stories didnt line up. To a cop, she was a potential criminal. The graves of twenty-seven boys murdered by a serial killer in Houston, their disappearances initially written off as runaway cases, were still a year from being found. That discovery would lead to the Runaway Youth Act being passed in 1974, federal legislation designed to help, rather than criminalize, street kids. By then my mother had been married to Red for almost two years and my big brother was four months old. According to his birth certificate, she was nineteen when he was born. But that was a lie as well.