Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Keven McQueen

All rights reserved

First published 2010

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.160.8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McQueen, Keven.

The great Louisville tornado of 1890 / Keven McQueen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-892-7

1. Louisville (Ky.)--History--19th century. 2. Tornadoes--Kentucky--Louisville-

History--19th century. I. Title.

F459.L857M38 2010

976.944041--dc22

2010002063

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to Ronda Foust and her son Eli Stansberry.

May they never reap the whirlwind!

Contents

They Contributed, Whether They Know It or Not

Laura All, Geneta Chumley, Drema Colangelo, Eastern Kentucky University Department of English and Theatre, Eastern Kentucky University Interlibrary Loan Department, Lee Feathers, Julie Foster, Rosie Garcia-Grimm, Tom Grazulis, Ken Grimm, Joe Hardesty, the Louisville Courier-Journal, the Louisville Free Public Library, the Darrell McQueen family, Kyle and Bonnie McQueen, Pat New, Amy Purcell, Gaile Sheppard, Mark Taflinger, Mia Temple, the University of Louisville Archives and everyone at The History Press. Also: the Conductor.

This book was edited by Lee Feathers of the Green Pine editorial services. www.greenpineeditorial.com.

PART I

Before

As is well demonstrated by Thomas Grazuliss website The Tornado Project, Americans have always had to fear death dropping from above in the form of natures most terrifying and violent storm. The earliest recorded American tornado struck Massachusetts on July 5, 1643and its all been downhill from there.

Part of the charm of reading old newspapers is seeing how our ancestors tried to explain and prevent these storms. A Mr. Barham, writing in the scientific journal Nature in 1877, opined that tornados formed when winds from the north and south pass[ed] each other on the left hand respectively. In the same year, Professor John H. Tice explained in a truculent article in the St. Louis Republican that, contrary to what other scientists and laypersons thought, a tornados destructive force came not from the wind it generated. Tice felt that tornados bent metal by somehow converting it to a semi-fluid state. In April 1890, General A.W. Greely, the head of the United States Signal Corpsthe nineteenth-century equivalent of the National Weather Servicetheorized that large, well-built cities would serve as barriers to a cyclones winds: [T]he writer believes a number of closely built brick or stone blocks, where each structure is so substantially built as to withstand tornadic winds without support from the adjacent buildings, may be considered tornado-proof. Farmers could ward off tornados by planting trees as windbreaks, thought Greely. (Sad experience has taught us, of course, that tornados can and will strike large, well-built cities if they feel like it and consider large trees hors doeuvres rather than barriers.) The idea that tornados could be thwarted if large walls were built west of major cities appealed to many; in 1896, Sergeant Dunn of New Yorks Signal Corps office pointed out the absurdity of this idea, which would require a wall about as high and broad as a mountain range, and its cost would make the national debt look insignificant by comparison.

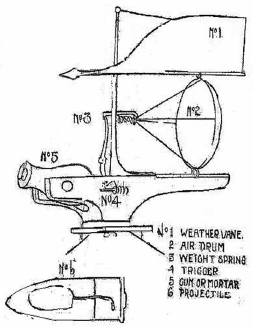

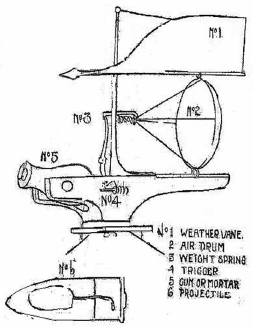

But perhaps tornados could be blown up with dynamite? Such was the plan of Professor H.A. Hazen of the Weather Bureau. In 1896, Hazen proposed that a line of lookout stations be placed in areas that were apt to be hit by the storms. Hazen believed that touching off dynamite at the stations by means of wires would blow approaching funnel clouds to smithereensor, at the very least, the explosions would deprive tornados of the electricity he thought necessary to fuel them. Fifty years hence, not a big town in the southwest will be without a tornado trap, Hazen confidently predicted. In 1899, Chicago artist E.D. Betts released a diagram of his invention, the cyclone annihilator, which he claimed would dissipate a tornado. The device was a cannon with an attached weather vane and air trigger. When a wind of over sixty-five miles an hour hit the vane, it would pull the trigger and fire a projectile into the approaching tornado, which was expected to throw it off its balance and scatter it into a harmless zephyr. The imaginative artist-inventor added, I should not hesitate to face the most destructive twister with a common pistol. It is possible that somebody tried Bettss scheme and found it uselessif the experimenter survived, that is.

Diagram for E.D. Bettss cyclone annihilator. Try it if you want to. Louisville Courier-Journal, June 25, 1899. Courtesy of the Courier-Journal.

Scientists still do not fully understand the atmospheric conditions that cause tornados to form, but it is known that the most powerful of the storms develop from supercell thunderstorms. Supercells contain a rotating column of air called a mesocyclone far above the earths atmosphere. The trouble begins, it is believed, when heavy descending air forces the rotating mesocyclone down to the earths surface. The rotating air column sucks up dirt and debris, darkens and becomes recognizable as a tornado. Some are long, thin and rope-like; some are hidden behind a wall cloud; some assume the classic funnel shape; and some take on the intimidating wedge shape. Luckily, most violent thunderstorms do not produce tornados; most of the twisters that are formed are weak and dissipate after doing minimal, if any, damage. The average tornado is 250 feet wide and produces winds of between 40 and slightly over 100 miles per hour. Most travel a few miles, lose their strength and disappear. The more formidable tornados, however, can be 1 mile wide, stay on the ground for hours, travel many miles and produce winds of over 200 miles per hour. The highest recorded wind speed from a tornado was 310 miles per hour, measured during the storm that devastated Moore, Oklahoma, on May 3, 1999.

All fifty of the United States have had tornadic activity, though residents of certain regions (especially the Midwest) have a lot more to worry about. Despite not being located in the nations infamous Tornado Playground, Kentucky has received its fair share of these violent storms. Richard Collins noted in his 1874 History of Kentucky:

The tornado is the highest manifestation of the irresistible force of the raging elements, and even in Kentucky, we experience enough to know that only the most substantial of structures or the everlasting hills can defy its power. It is, however, a source of consolation to know that its visitations in Kentucky are not very frequent, [and]

Next page