| TOUCHSTONE

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020 |

Copyright 2007 by Nancy Mathis

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

T OUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mathis, Nancy.

Storm warning : the story of a killer tornado / Nancy Mathis.

p. cm

Includes bibliographical references.

1. TornadoesOklahomaOklahoma CityHistory20th century. 2. Tornado warning systemsOklahoma. 3. National disaster warning systemsUnited States. I. Title.

QC955.5.U6M38 2007

363.34'923097663809049dc22 2006051237

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-3921-6

ISBN-10: 1-4165-3921-2

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

For my mother

The close-knit world of the tornado and severe thunderstorm forecaster often seems somewhat demented to those not knowledgeable in this discipline. This apparent derangement is based on our seemingly ghoulish expressions of joy and satisfaction displayed whenever we verify a tornado forecast. This aberration is not vicious; tornadoes in open fields make us happier than damaging storms and count just as much for or against us. We beg your indulgence, but point out the sad truism that we rise and fall by the blessed verification numbers. There is a fantastic feeling of accomplishment when a tornado forecast is successful. We are really nice people but odd.

T HE LATE C OL . R OBERT C. M ILLER ,

U.S. A IR F ORCE METEOROLOGIST

And, behold, there came a great wind from the wilderness, and smote the four corners of the house, and it fell upon the young men, and they are dead; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee.

J OB, I:19

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

O N THE FIRST WARM DAY OF each spring, an elderly American Indian woman would grab a hoe and a flashlight and head down into the storm cellar. This six-foot-square concrete bunker doubled as a frost-free refrigerator for the canned beans, peaches, and assorted other fruits and vegetables she had harvested the previous fall. Wielding the hoe like a makeshift guillotine, she cleared the room of any hibernating rattlesnakes, copperheads, or other small creatures that might have found their way into the shelter during the winter.

With the cellar swept clean, the spiderwebs and animal carcasses removed, my grandmother was now ready for the tornadoes and thunderstorms that would surely come in April, May, and June. Well, almost. She had one more weapon in her arsenal. At the first sign of a dark cloud rumbling in from the east, she would take an axe, point it at the clouds, and swing the blade hard into the ground, certain that this bit of native magic would cause the storm cloud to split and keep us safe from the tornadoes. I always suspected there was more to tornado safety than that, but in the 1960s and 1970s, an axe in the ground was just as accurate as the next days forecast.

I spent many hours as a child in my grandmothers dank cellar, listening to the winds whistle through the cinder-block vents and the hail hammer the tin door, imagining what was happening outside. My grandmothers fear of tornadoes was hardly unique and not at all unwarranted. The small eastern Oklahoma town of Tahlequah, where I grew up, was the capital of the Cherokee Nation. The site was chosen in a valley because it was believed to be protected from tornadoes. Thats one of many myths about the twister; in fact, there are no safe locations.

The tornado remains a great puzzle, its many myths steeped in folklore. This book is the life story of one tornado on one day and its consequencesnot just any tornado, but the most powerful twister ever to strike a metropolitan area. It is the life story of a tornado researcher and his legacynot just any researcher, but the most brilliant meteorological detective of the twentieth century. And it is the story of the lives touched with such a harsh hand on May 3, 1999.

Meteorology is one of the most complex of the sciences. Indeed, it took a meteorologist to develop one of the new fundamentals of science: chaos theory. The breakthrough happened in 1961 while American Edward Lorenz was working with a numerical computer model for weather predictions. While attempting to repeat one weather pattern, in order to save time, Lorenz entered only three decimal places, .506, instead of the six, .506127, the computer could store. He entered his sequence of numbers expecting to see the same weather pattern take shape on the screen in front of him. What appeared was a radically different prediction. Hed assumed that the difference of one part in ten thousand would be minimal, that the picture that emerged would be at least similar to what hed seen before. Instead, the two patterns bore no resemblance to each other.

In 1979, Lorenz wrote a landmark research paper exploring this phenomenon, Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterflys Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas? Eventually, chaos theory also became known as the Butterfly Effect, referring to a small act that creates great consequences. Like a small break in the clouds over Oklahoma on May 3, 1999. Like a missed target in Japan on August 9, 1945. Like a mothers brief moment of indecision. Like my grandmother burying an axe blade in the ground.

Chaos theory has been much on display since Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans and the Gulf Coast in September 2005. All actionsor lack of actionshave consequences. The hurricane and the tornado are different meteorological animals, but they send us the same message: we are at their mercy, and we ignore them at our own peril.

N ANCY M ATHIS

STORM WARNING

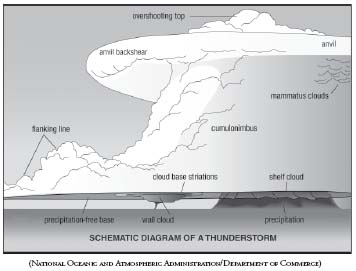

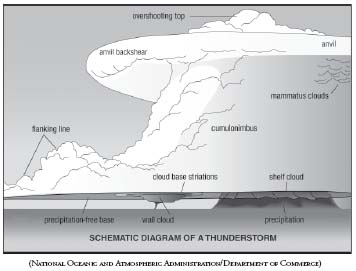

B EFORE THE GREENISH RADAR SCANS, BEFORE blurry photographs from satellites, before television or television meteorologists, and before the snappy twenty-four-hour-a-day Weather Channel, there was this: the faint flicker of lightning and the distant growl of thunder on the prairies horizon. This was what amounted to a storm warning on the plains.

The far, open sky filled with mountainous cauliflower clouds that grew fat with rain and hail, and those dark olive-hued clouds could conceal the most powerful force known in natureor not. No one knew for sure, no mere mortal could; after all, the tornado, or cyclone as it was called on the plains, was an act of God, an Old Testament punishment for ill deeds or a test of faith. It was capricious and deadly, leaving the living to bear witness that the great wind came straight from heaven, or so it seemed.

April 9, 1947, sometimes seems like yesterday for Ramona Kolander. Not that she dwells on the day, but its impossible to forget a day that turns your life upside down. Not even a day really, just a few seconds, and a lifes course is altered forever.

I never would have lived the life I lived without that tornado, she explained. It served as the demarcation in her life, the before and the after.

Ramona was a senior at Shattuck High School at the time. Shattuck was a frontier town in far northwestern Oklahoma, situated at the edge of no-mans-land and the Texas border. It was flat and empty, and the emerald fields that bowed with the winds would soon turn golden as harvesttime approached. The Kolanders, like most of their neighbors, grew winter wheat, a difficult, fickle, and occasionally profitable occupation.