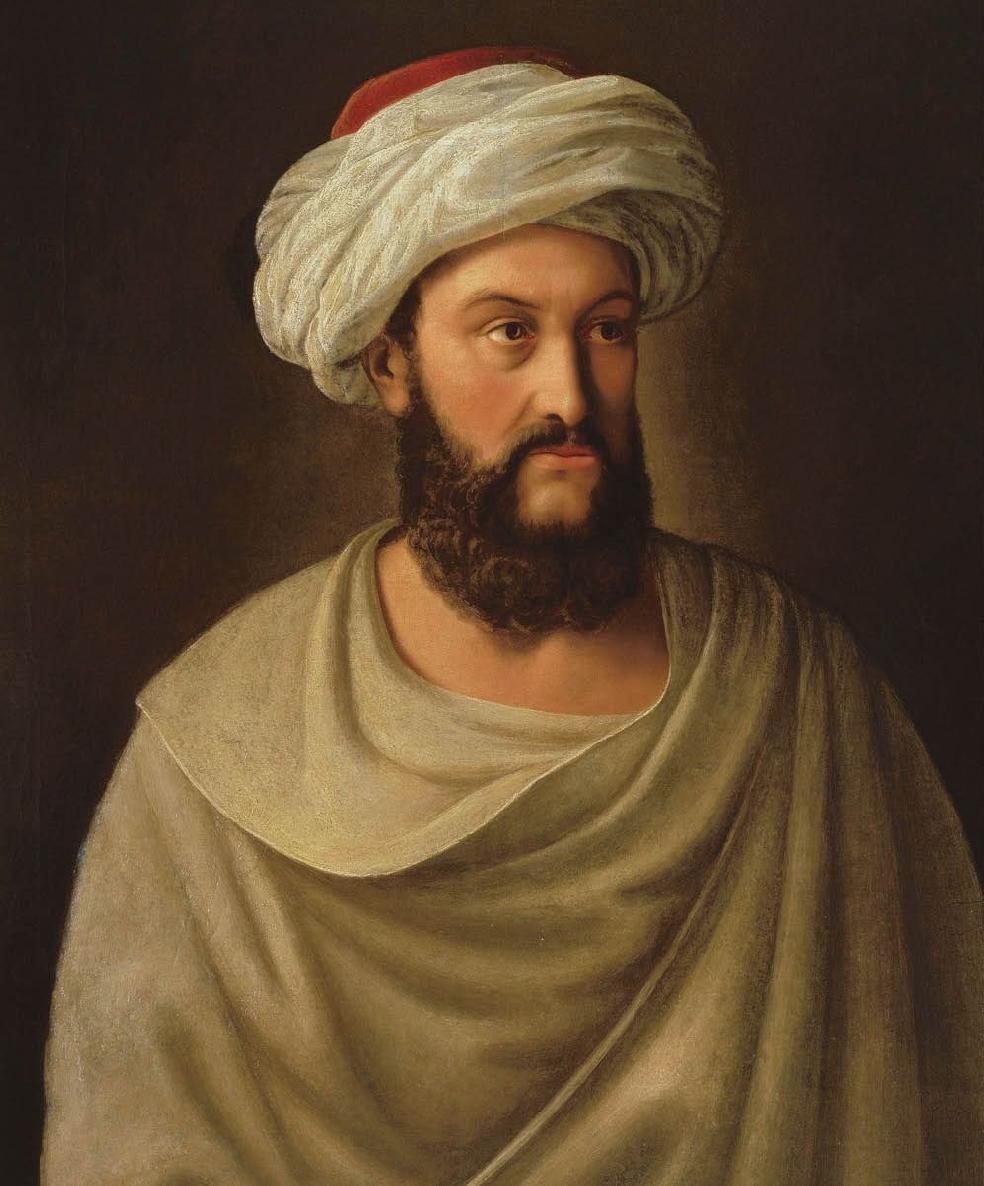

The famous explorer Johann Burckhardt, who became fluent in Arabic and spent years venturing into the desert in disguise.

The remarkable hidden enclave of Petra in the Jordanian desert. Burckhardts were the first Western eyes to see it.

Egypts ruthless ruler Pasha Muhammad Ali was struggling to establish the country as a modern nation. He was quite happy to exchange the past for the present. Ali cunningly played the consuls of the worlds two most dangerous and predatory nations off against each other for Egyptian gain.

Belzoni was the most unlikely Egyptologist in the world, but Burckhardt saw beneath the surface: this was a very determined man with a range of rare skills, particularly when it came to engineering. Belzoni delighted in the explorers stories, one of which concerned the head of the Young Memnon, which lay separated from its colossal body in the burning sands on the west bank of the Nile. It was an effigy of Ozymandias, the Greek name for Ramesses II, and the inspiration behind Shelleys sonnet.

Armed with Burckhardts information, Belzoni rampaged around Egypt, trying to stay one step ahead of Drovetti and his sidekick, the military deserter Jean-Jacques Rifaud. The French had been granted a licence to excavate at Thebes, and the remarkable complex at Karnak that the Egyptians knew as Ipet Issu (the most select of places) a fact that infuriated Salt, who knew that they had stolen a march on him.

Burckhardt and Belzoni persuaded Salt that the Young Memnon, stuck in the desert near Thebes, should be resurrected and given to the British Museum. Napoleons army had already tried to move the statue, using gunpowder to blow off its wig, and found it an impossible task.

Unfortunately for Belzoni, Drovetti was one step ahead of him. When he asked the local Bey for permission to remove the statue, Drovetti arrived in person. He told Belzoni that no labour would be made available to help in the enormous task. Undeterred and ever-resourceful, Belzoni realized that the best way to move the statue was to use the Niles waters. He also realized that there was a ticking clock: the great river would flood in a months time. The race was on. Belzoni found the statue and proceeded to hire 80 labourers of his own. With 14 wooden poles, four palm-leaf ropes and four sledge rollers, he set about moving Ozymandias.

He often worked at night avoiding the daytime heat: he levered rollers underneath the statue front and back. Some dragged, some pulled; no doubt Belzoni added his great strength. Then everyone hauled the pink granite statue inch by inch towards the river, moving the back roller to the front as they progressed.

After a month of waiting for Salts promised boat to turn up, Rifaud arrived aboard a large boat bound for Aswan. He refused Belzoni use of the boat. Every day, the Nile was getting lower, and even Belzonis bribes had ceased to have any effect on the locals: he could not get out of Thebes. Until Drovetti made the mistake of presenting another local dignitary, the Casheff of Erments, with a jar of sardines. The Casheff was outraged by such a pathetic gift. Heaping Belzoni with lavish praise, he invited the strongman and his English wife, Sarah, to a feast. The Great Belzoni would get all the help he wanted, could take any boat he wanted any statues, for that matter. Never one to turn down an opportunity, Belzoni grabbed a few statues from Karnak for good measure, built a mud ramp down to the Nile where for one heart-stopping moment the Young Memnon sank into the mud and set off with Sarah for Cairo.

No easy task: the Great Belzoni and his workmen haul away at the Young Memnon.

Belzoni had caught the bug. Using methods that would make a modern archaeologist scream he thought nothing of opening sealed tombs with a battering ram he plundered everything of value in sight. He dug through 20 ft (6 m) of hardened sand to get at the monuments of Abu Simbel, rediscovered the entrance to the Great Pyramid and found five tombs in the Valley of the Kings, including that of Seti I, thereby paving the way for a long series of important excavations that others could now undertake.

In 1844, the American vice-consul, George Gliddon, made an emotional appeal. All this pillaging had to stop: Words cannot express our rage about all the demolition that has taken place here [at Karnak].

Fortunately, there were signs of a new, more thoughtful approach developing among individuals who would approach Egypts majestic past with greater respect. The new cast included a French artist named Frdric Cailliaud, who would diligently copy hundreds of ancient documents and papyri. William Bankes also copied thousands of inscriptions, in situ , including the name of Ramesses II. The efforts of these two men, one French and one English, eventually helped a young man called Champollion to decipher the Rosetta Stone.

Giovanni Battista Belzoni (17781823)

Born in Padua, the son of a barber, Belzoni had a varied career, first studying hydraulics before working as a barber in the Netherlands. A meeting in Malta with Ismael Gibraltar, an emissary of Muhammad Ali, the Khedive of Egypt, took him to Egypt where, on the recommendation of Johann Burckhardt, he began work for Henry Salt. He is most noted for his work at the Ramesseum at Thebes, the great temple at Edfu and Abu Simbel and Karnak.

Greece and the Democratic Ideal

Together, the pen and the sword galvanized the first ever formal excavations in Greece.

When Johann Joachim Winckelmann wrote his influential History of the Art of Antiquity he portrayed Classical mainly Greek art as the pinnacle of European civilization. The German cobblers son was riding a wave of intellectual curiosity fed by Greeces isolation under Ottoman rule.

To European societies, the Classical civilizations of Greece and Rome embodied the best of civic and artistic virtues. Indeed, the excavations of Pompeii, which had begun in the mid 1700s, had become a significant tourist destination. Democratic ideals were the silent symbolism behind many of the new public buildings in France, Britain and the fledgling USA. Winckelmann added to that the notion that a societys civil success was pinned to the quality, or nobility, of its art. The evolution of art, he argued, paralleled the life cycle of civilizations.

Pro-Greek sentiment was exploding across Europe, fuelled by accounts of atrocities committed by the occupying Ottomans. The British colonel Martin William Leake was sent on a spying mission: he brought back booty which is now mainly in the Fitzwilliam Museum, in Cambridge.