The dialogue in this book is based on interviews, letters, diaries, memoirs, contemporary newspaper articles, magazine features, film footage, and official reports of the people involved. Whenever possible, I used contemporary sources. While reconstructing the exact words used in a particular conversation some seven decades after it took place is nearly impossible, Ive worked hard to accurately reflect the nature of the conversation and the words used that the participants themselves recalled or wrote about at the time.

March 3, 1943

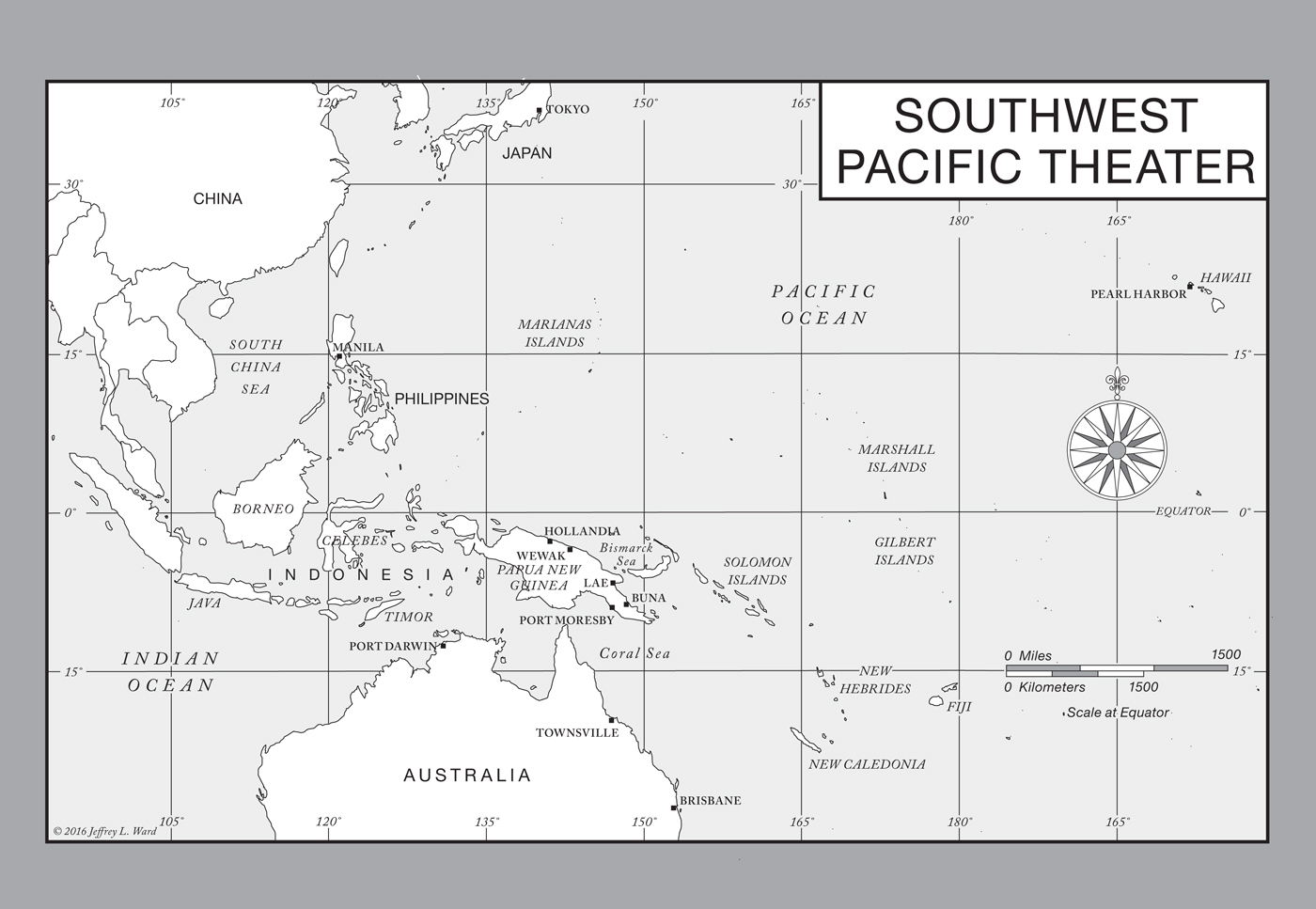

Thirty miles off the Northern New Guinea Coast

T he sharks fed, and men screamed. Those who could fought back, kicking and punching in desperation as the great whites and hammerheads reared up from the depths, their jaws snapping off limbs or tearing men in half. The dead lay floating around the living, blood so thick on the whitecapped swells that those who bore witness to the scene swore the Bismarck Sea turned red that day.

A lucky few found refuge in battered lifeboats, or had scrabbled atop hunks of debris left over from a dozen shipwrecks. Others floated in life belts, treading water among the corpses and wreckage. Thousands had already died. The wounded cried for help they knew would not come.

A sound rose in the distance. At first, it was weak, a mere buzzing barely heard over the chaos on the waves.

The broken men fearfully turned their eyes skyward. The Americans had returned. A few readied waterlogged bolt action rifles or light machine guns theyd carried over the sides of their sinking ships. Such weapons offered a pitiful defense to the juggernaut fast approaching, but they were all they had left. Their air force had been vanquished. Their navy had either been destroyed or driven off. Now, these men bobbed in the Bismarck Sea and knew there would be no miracle to save them.

The sounds of onrushing engines grew deafening, but the straining men could see no aircraft. In the distance, a few appeared thousands of feet above them. Those made no difference to the men in the water, and they were not the ones whose engines filled their ears. The real threat remained unseen.

The water churned around them as if pummeled by rain from a tropical storm. Lifeboats were torn apart, the debris raked by the bullets from scores of heavy machine guns. Their thunderous reports reached the survivors ears a moment later. Dark, predatory shadows sped over them. The American bombers came in so low and so fast they couldnt be seen until they were practically overhead.

They were new weapons, engineered for a new type of air warfare that had caught the men in the water completely by surprise. There had been no effective defense against them, and their ships were transformed into bullet-riddled conflagrations in mere minutes. In retrospect, the lucky ones had died aboard ship.

The growling engines receded, but only for a moment. They would return for another pass.

Nine thousand feet above the death and misery in the water, the middle-aged pilot, a father of four and a devoted husband who had engineered their fate, watched the scene below through eyes once full of mirth and now devoid of mercy.

All the while, the sharks continued to feed.

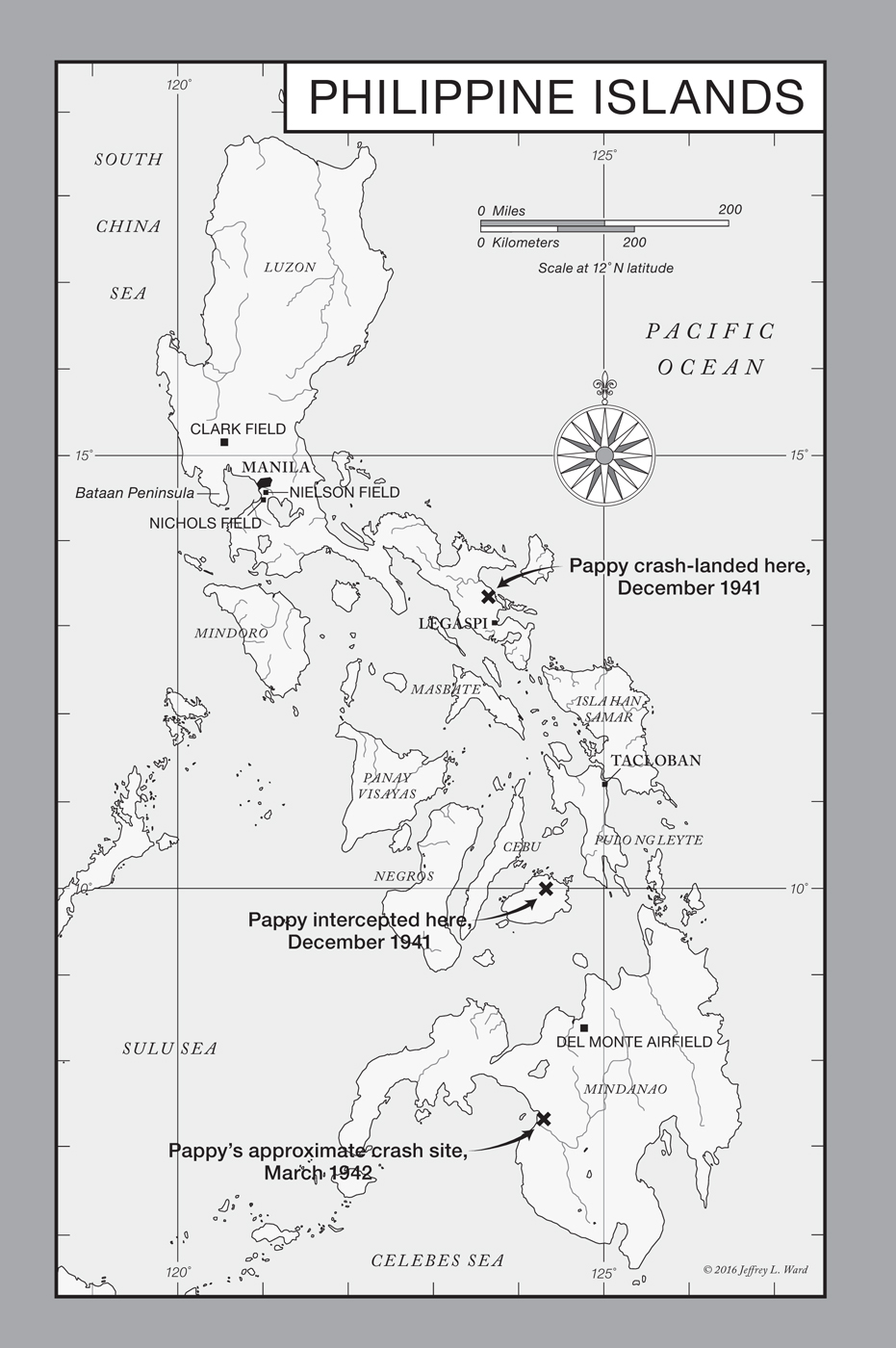

December 1941

Manila, Philippines

I n a handmade four poster bed, beneath a white, homespun quilt, Paul Irvin P.I. Gunn lay beside his wife of twenty years. Pollys almond-colored hair, always meticulously braided, adorned her pillow. They slept close, paired as lovers whose fire for each other never ebbed. Other couples came and went. These two had thrived despite everything a hard and dangerous life threw at them.

On P.I.s nightstand rested a standard U.S. Navy BUSHIPS Hamilton wristwatch, a legacy of a career now four years in his rearview mirror, but still worn every day. Slim, solidly built, and scuffed from countless adventures, the timepiece matched P.I.s own physical traits perfectly. Over the years, both man and watch survived everything from raging ocean storms to plane crashes and combat missions over Nicaragua in underpowered biplanes. The watch had become part of the man long ago. The tiny second hand spun out another minute until the watch showed precisely four thirty.

In the bed, P.I.s gray-blue eyes shot open. He flung back the quilt and sat up like an uncoiling spring. For him, there was no slow transition between sleep and consciousness. Like the flip of a light switch, he went from dormant to full power every morning at exactly 0430. He never needed an alarm clock; his own internal one was better than anything even the Swiss could produce.

His bare feet found the polished hardwood floor, which the familys servants buffed with coconut husks they strapped to their feet. That weekly process was a source of fascination for P.I. and Pollys two young boys.

Hit the deck! P.I. called out, his voice booming through the house. A moment later, he padded into the bathroom to put in his teeth. Long ago, while pioneering the use of float planes on Navy warships, hed landed his aircraft beside a cruiser and taxied up alongside it. A crane swung out over the side and hooked his aircraft with a cable. As the crew winched the craft aboard, a huge swell slammed broadside into the vessel, which caused it to list sharply, before rolling back on an even keel. The sudden movement flung P.I.s plane like a pendulumdirectly into the cruisers side. The force of the impact threw P.I. face-first into the instrument panel so hard it permanently damaged his teeth. Later, he had a dentist pull them all and make him a set of dentures.

His morning routine was short and to the point. He turned the shower on, waiting impatiently for the hot water to come. He had stuff to do and patience never suited him. The water warmed and he stepped inside. He showered quicklyno lingering there to enjoy the water on his middle-aged muscles. Showers were functional necessities, not indulgences. He finished and pulled a towel off the nearby rack.

Long ago, back when he wore leather and silk to work every morning, he learned to shave at night. It was an old pilot trick, passed from one generation to the next in the era of the open cockpit biplane. Silk scarves helped protect a pilots neck from chafing against leather collars, but the wind would whip raw freshly shaved skin. Those who dared the early fabric and wood flying machines were uncomfortable enough in basket seats and freezing environs, so they took to scraping their stubble before bedtime in order to give their flesh time to toughen back up.

Though his open cockpit days were long past, P.I. was nothing if not a creature of habit.

He finished drying off and grabbed his clothes. Despite the tropical heat, P.I. always favored long-sleeved khaki button-down shirts for work. Part of this was a sense of professionalism. Mostly, though, it was a way of hiding an indiscretion from his past life.