FLIES IN AMBER

Pretty in Amber to observe the forms

Of hairs and straw and dirt and grubs and worms.

The things, we know, are neither rich nor rare,

But wonder how the devil they got there!

Alexander Pope, Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot

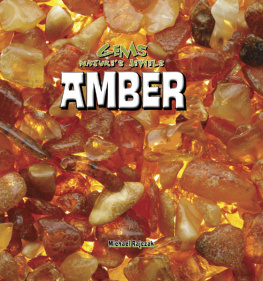

I am standing in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. In a glass case in front of me are some small, irregular beads of dark, honey-coloured amber. Discovered in a Mycenaean tomb in Crete by Sir Arthur Evans, they date from between 1700 and 1300 BC , the dawn of classical civilisation. At around the same time, in north Wales, hundreds of amber beads were placed in a stone-lined tomb along with a body wrapped in the spectacular gold shoulder ornament known as the Mold Cape, now in the British Museum. Amber has been found in the tomb of Tutankhamun and in the ruins of Troy . The Etruscans imported large amounts of it, which they used to adorn jewellery, as did the Romans after them.

My fascination with the substance began as a child. My father had a small piece of opaque, tawny amber, about an inch long, crescent-shaped and holed in the middle like a bead. I have it on the desk in front of me as I write. It was a relic of his days as an apprentice telephone engineer in pre-war Germany, and he would use it to demonstrate its electrostatic properties. After suspending the amber from a length of thread, he would rub it on his sleeve and hold it over an ashtray, so that flakes of ash would fly up and adhere to the resin, like iron filings to a magnet. It was the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus, around 600 BC , who first discovered ambers ability to attract seeds, dust and fibres after being rubbed on wool. The ancient Greek name for amber, elektron , is the root of the word electricity.

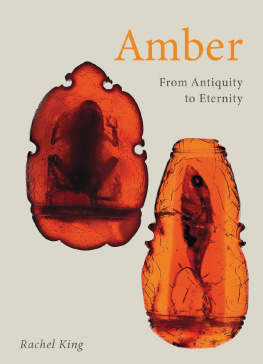

The amber came from the southern and eastern shores of the Baltic, where it was washed up by storms and gathered by local people. It began its existence as resin oozing from the trunks of conifers in the prehistoric forests of northern Scandinavia between 40 and 50 million years ago. Carried downstream by rivers, the resin settled in a layer under what later became the southern Baltic some 10,000 years ago as the glaciers of the last Ice Age receded. In the course of time, it was transformed into amber by the processes of polymerisation and oxidation. Some even made its way into the North Sea to wash up on the shore of Suffolk. Amber is also found in Siberia, the Far East, Mexico and the Dominican Republic. It was Dominican amber that inspired Michael Crichtons 1990 novel Jurassic Park , and the Steven Spielberg film that followed. The premise, that a mosquito trapped in amber could contain a sample of dinosaur DNA, appeared far-fetched at the time, but since the discovery in 2015 of the feathered tail of a small dinosaur in a piece of Burmese amber, it seems slightly less improbable.

It is the Baltic deposits, however, that are the most plentiful, producing around 90 per cent of all the worlds supply, their chemical composition making them easily distinguishable from amber originating elsewhere. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, these golden nuggets had mysterious properties: cool in summer, warm in winter, they often contained glimmering fragments of plants, insects and even small vertebrates, frozen in the moment they were caught in the trickling honeytrap. Amber was attributed with healing powers, and gave rise to myth and legend. In his Historia naturalis , the Roman writer Pliny the Elder dismissed the old tales in favour of a brisk scientific explanation: Amber is formed by the pith which flows from trees of the pine species, as a gum flows from cherry trees and resin from pines. A remarkable understanding that was to be lost for more than 1,500 years.

But how did amber find its way from the Baltic to the shores of the Mediterranean, a thousand kilometres to the south? Pliny stated that the substance came from the islands of the north of the Northern Ocean. So highly was it prized that the manager of Neros games sent an emissary to the far north to collect it. Pliny gave an account of the expedition:

There still lives the Roman knight who was sent to procure amber by Julianus, superintendent of the gladiatorial games given by Emperor Nero. This knight travelled over the markets and shores of the country and brought back such an immense quantity of amber that the nets intended to protect the podium from the wild beasts were studded with buttons of amber. Adorned likewise with amber were the arms, the biers, and the whole apparatus for one day.

In his Germania , written around AD 98, the historian Tacitus mentions a tribe called the Aesti who lived on the coast to the right of the Suevian Ocean and collected that curious substance from the shallows. He noted that the Aesti could not see any use for amber and were pleasantly surprised to be paid for the pieces they gathered. For the poet Juvenal, writing in the early 2nd century ad , the popularity of this luxury item was a sign of Romes decadence: in his Ninth Satire, he associates the fashion for holding balls of amber to cool the hands in summer with effeminacy. The trade was still going in AD 301, when amber was one of the goods specified in the Emperor Diocletians edict regulating prices.

Many people view globalisation as a recent phenomenon and fear it as a threat to national identity. Yet the world has been criss-crossed by trade routes since the Neolithic. Phoenician seafarers traded tin from Cornwall; Roman coins are found throughout India; Arab silver dirhems in Anglo-Saxon burials in England. Amber is an ideal commodity for long-distance trade like silk and spices, it is light, portable, and of high value. But is the written evidence of Pliny and others supported by any physical trace of the route it took?

On a wet and blowy Monday night in February 1925, geographers, explorers, historians and archaeologists gathered at Lowther Hall, the headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society on Kensington Gore in London. The distinguished audience listened transfixed as a young scholar, soldier, archaeologist and poet, J. M. de Navarro, tracked the course of an ancient trade route comparable to the Silk Road from China to the Mediterranean. The sheer length of the route, and its duration, from the Neolithic to the fall of the Roman Empire and beyond, were as thrilling as De Navarros methodical and detailed presentation was convincing.