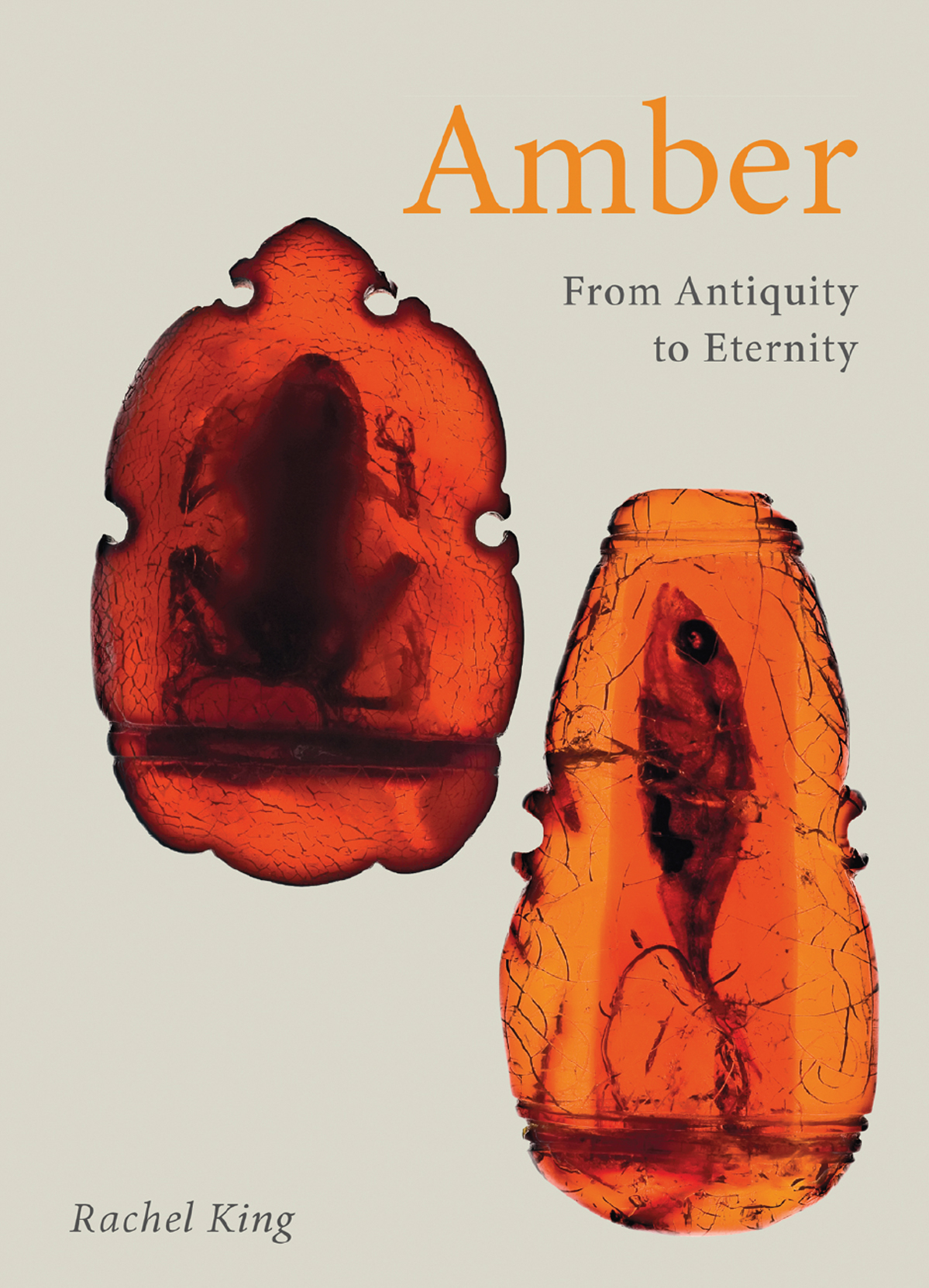

Amber

Amber

From Antiquity to Eternity

Rachel King

REAKTION BOOKS

For Iris, for Benot, for Thilo

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2022

Copyright Rachel King 2022

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789145922

Contents

one

Amber: What, When, Where?

two

Legend and Myth

three

Ancestors and Amber

four

Unearthing Amber

five

Making and Faking Amber

six

Accessorizing with Amber

seven

Artistic Ambers

eight

Lost Ambers

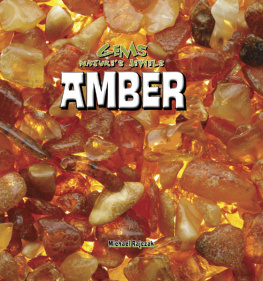

1 Specimens of amber in their myriad colours from a private collection in Gdask, Poland.

2 Notable deposits of ambers and subfossil resins. The locations named on the map above are discussed in this book.

one

Amber: What, When, Where?

W here do I usually begin when I am describing amber to somebody else? Colour. I mostly find that people have some sort of sense of one or some of its many hues: cream, honey, caramel, cherry, claret and even coffee. Many are so familiar with the golden variety as to be able to approximate a colour when amber is used as a descriptor. Whether noun or adjective, the word amber calls to mind clarity, warmth, polish, transparency and beauty (). Ambers irresistible appeal to the senses has been explored for thousands of years. This book is about the fascination and excitement surrounding amber and how it has attracted people of all backgrounds down the ages. It is about the approaches taken throughout history to some quite simple questions: what is it, where does it come from, why is it as it is?

Much of the modern literature dealing with amber has focused on certain aspects of this fascinating material. These works ask and answer specific questions, usually related to the background of their authors or the purpose of the exhibition they accompany. In recent years, the number of monographs has grown. Yet, in many cases, the approach is still the traditional one whereby books assemble information in siloed chapters rather than uniting, confronting and interweaving. The chapters in this book set out to bring different understandings and approaches together, showing the richness, longevity and depth of humanitys engagement with amber. They trace elaborate ideas, personal stories, political and scholarly disputes, questions of national and personal identity, and touch on amber in religion, art, literature, music and science.

For centuries, the story of amber in English and other European languages has privileged the history of amber in what is now called the Global North. New sources of amber are being discovered with ever-greater frequency, and the study of amber worldwide has developed rapidly in recent decades. This book casts its net further to Africa, Asia, Central and South America and Australasia, shedding light on their long histories of human interaction with amber and highlighting common features of human engagement, as well as those which are unique. It is a modest attempt to test the boundaries of traditional histories of amber and endeavours to reimagine what it means to present the story of this enthralling material in the twenty-first century. As will become clear throughout, thorny ethical and moral questions cannot be avoided. These issues not only shape the ways in which humans connect with amber today but affect its future.

DEFINING AMBER

There has never been a monolithic definition of amber in world history and there can be no single definition of amber in a study of this scope. It seems likely that humans have wondered about its nature for as long as it has been known. An inability to neatly and cleanly define amber has always been one of the challenges. Throughout history, how amber was and is understood has changed dramatically as knowledge standards have themselves shifted. There are no fewer opinions as to what amber may be than there are names for it opined the German doctor Georg Bauer (pen name Agricola) back in the sixteenth century. Amid all the ideas, there are sometimes moments of wide-ranging agreement among like-minded parties. The Encyclopedia Britannica defines amber from a scientific perspective, specifically in relation to the earth sciences, the history of time and fossils. In other words, it presents the definition used by such professions as geologists, botanists and organic chemists: amber is a fossilized resin produced in a geological era long before this one. Amber is, in effect, an ancient tree resin.

YOUNG AND OLD RESINS

Trees produce resin when they have been damaged by fire, climactic or environmental disruption, disease or insects. It is their natural way of sealing wounds (). Of all the substances plants secrete, resin is the only substance that has the potential to become amber. However, not all resins will fossilize, as fossilization which means the process by which a once-living thing or traces of it become preserved only occurs when the resin molecules fully link and cross-link (polymerize). This process of chemical change starts the moment the resin is extruded and meets the light. It continues as the resin matures, usually buried by soil or sediments where it is affected by the different elements, temperatures and pressure of the local environment, as well as the oxygen content thereof. Amberization, as this process of maturation is sometimes called, ends when the substance has lost all of its volatile constituents and become completely stable. Confusingly, both the resin and the plant and animal remains it entombs are referred to as fossils.

3 Resin oozing from a tree trunk, Dalkeith Country Park, Midlothian, Scotland.

Young, recently hardened resins are called copals. The word copal derives from the Nahuatl word copalli, and, like amber, has a complicated history. In pre-Columbian Meso-America, the word had a locally specific meaning. Over the last five hundred years, the word has expanded to mean a variety of subfossil resins. In copals, the molecules are incompletely cross-linked and some are still volatile. A drop of alcohol makes their surfaces tacky; a flame melts them. Copals can be polished, but they will quickly craze and crack as the freshly exposed oils, acids, alcohols and volatile aromatic components evaporate. These components will gradually be lost if copals are left in the soil and the conditions are right. There are, in effect, many ambers because everything along the sliding scale of hardness can be, or may at one time or other have been, perceived to be amber. Culturally and historically speaking, amber is the name for a wide variety of scientifically diverse yellow-looking resins.