Contents

Guide

Page List

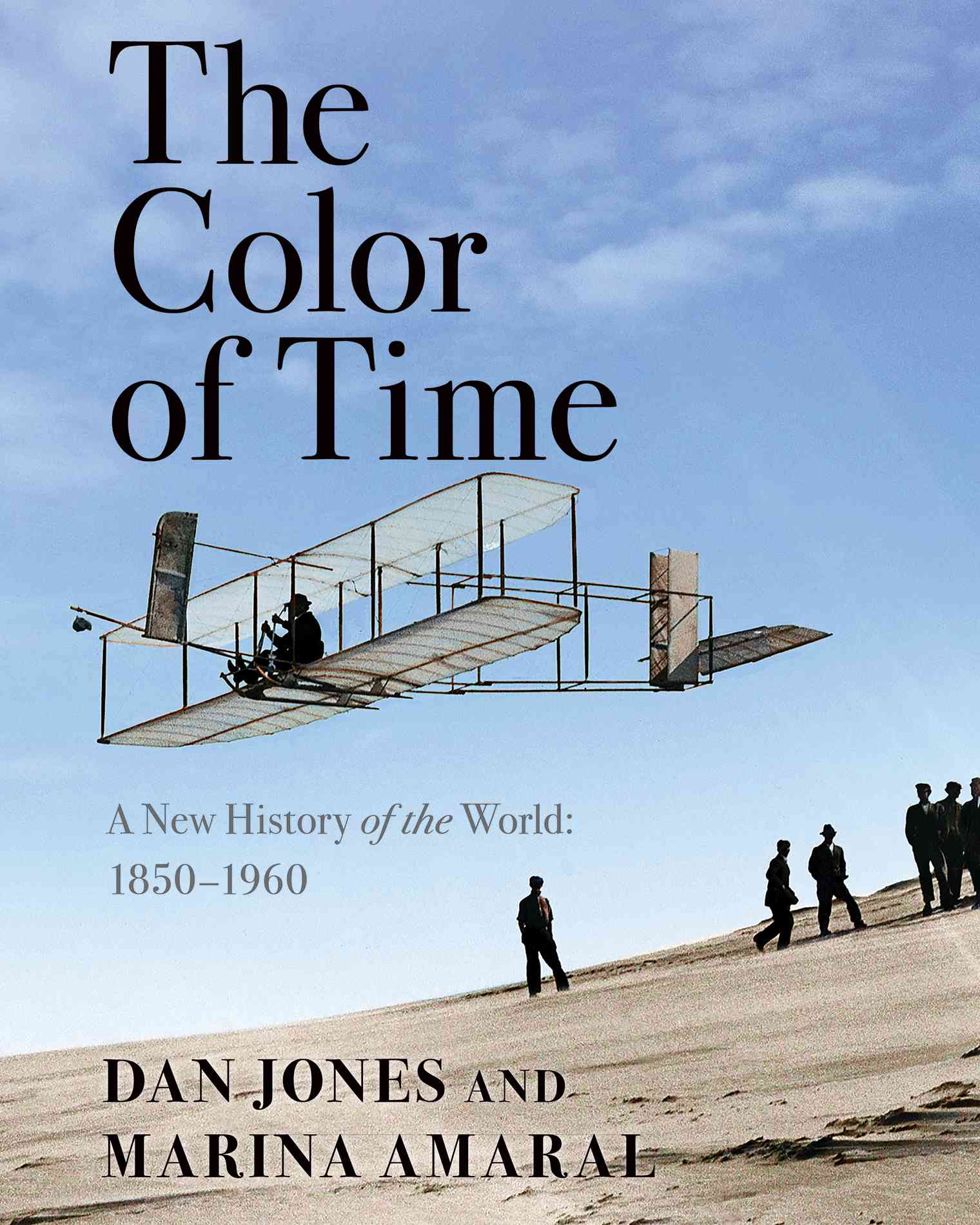

Dan Jones

&

Marina Amaral

The Color of Time

A NEW HISTORY OF THE WORLD:

18501960

John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier photographed by Toni Frissell at their wedding reception, Hammersmith Farm, Newport, Rhode Island: 12 September 1953

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following for their invaluable help in creating this book:

Charlotte Araya Moreland, Alastair Bruce, Georgina Capel and all at GCA, Phil Curme, Ned Donovan, John Ford, James Holland, Dr Dan Jackson, Eloise Jones, Mads Madsen, Professor Jonathan Parry, Dr. Fern Riddell, Andy Robertshaw, Saad Salman, Robin Schfer, Dr Gajendra Singh, Simon Sobolewski, Dr Phil Weir and Alex Winkworth.

Particular thanks to Anthony Cheetham and the whole team at Head of Zeus including Georgina Blackwell, Dan Groenewald, Clmence Jacquinet, Claire Kennedy, Richard Milbank, Suzanne Sangster and Isambard Thomas.

PICTURE CREDITS

The photographs in this book are reproduced by kind permission of Getty Images, with the exception of the following:

(Library of Congress)

(Wikimedia Commons)

(Bibliothque Nationale de France)

Note: We have ordered this e-books content to match the physical version of the book. The printed version of The Color in Time sometimes places photographs before the text captions describing them; other times, photos are placed after the text descriptions. To eliminate confusion, we have placed  symbols above any text paragraph that comes before the photo it describes. Otherwise, text without a hand symbol will always come after the photo it describes.

symbols above any text paragraph that comes before the photo it describes. Otherwise, text without a hand symbol will always come after the photo it describes.

The archaeologist Howard Carter examines the coffin of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun (

c.13321323 BC), whose tomb he discovered (virtually intact) in the Valley of the Kings in 1922

E arly in the 16th century Leonardo da Vinci jotted in his notebook a few lines about perspective. As objects get further away, he wrote, three things seem to happen. They get smaller. They become less distinct. And they lose colour.

Da Vinci was writing about painting, but his words can be applied literally to photography and metaphorically to history. We understand that the world has always been as vivid, immediate, colourful and real as it seems to us today. Yet vivid and colourful is seldom the way we see the past now. Photography, which became part of the historical record with the popularisation of the Daguerreotype in 1839, was for its first century a medium that operated almost exclusively in black and white. The view behind us is partial and faded. We see history, to repurpose St Pauls phrase to the Corinthians, through a glass, darkly.

This book is an attempt to restore brilliance to a desaturated world. It is a history in colour. Among the following pages are collected 200 photographs taken between 1850 and 1960. All were originally monochrome, but they have been digitally colourized with the effect we hope of making us look afresh at a dramatic and formative age in human history.

Each picture included here is interesting in its own right. Together they have been selected and organized as a collection, accompanied by extended captions that flow one from another to form a continuous narrative: a story that takes us from the Crimean War to the Cold War and from the steam age to the space age. We begin in an age of empires and end in an age of superpowers. Here is a stage on which dance titans and tyrants, murderers and martyrs, geniuses, inventors and would-be destroyers of worlds.

The photographs come from a wide range of sources. Some were originally albumen prints, created through a complicated process involving long exposure-times, glass sheets and collodion, egg whites and silver nitrate. Others were shot on medium-format or even 35mm film roll. Some were created for private pleasure, others for sale as postcards or for publication in mass-market magazines. Some have an astonishing sharpness of definition; others bear the inevitable and irresistible patina of age. All ended up being preserved, digitized, and made available through modern picture archives, from where they can now be downloaded in high resolution.

Conscience dictates that before you sit down to colourize a historical photograph, you must do your homework. A portrait of a soldier, say, will contain uniforms, medals, ribbons, patches, vehicles, skin, eye and hair colours. Where possible, each detail must be verified: traced via other visual or written sources. There is no way of knowing the original hues just by looking at the different shades of grey. The only course of action is the one familiar to every historian, whatever their speciality: dig, dig, dig.

With as much information as possible to hand, you start to colourize. Although the canvas on which you work is a computer screen, every single part of the picture is coloured by hand. Theres nothing algorithmic in the process. The tools may be digital, but the basic artists technique has not changed since Leonardos day: slowly starting to apply colours over colours, mixing them through hundreds of layers, trying to capture and reproduce a specific atmosphere that is (in this case) consistent with the photo itself. Lighting matters. So too texture. Tiny details are of the utmost importance. Patience is a virtue. A single photograph can take anything between an hour and a month to colourize. And sometimes, after all that work, you must still accept that for a whole variety of reasons, the result is unsatisfactory. It just looks wrong. Back to the archive with it. Some things must remain black and white.

This book is the product of two years collaboration. In selecting the photographs we have tried to spread our gaze across continents and cultures, and to commingle the famous with the forgotten. We have tried to honour the dead and do justice to their times. We looked at perhaps 10,000 photographs. We agonized, and changed our minds. We tried to pack in as much as we could, knowing all the while that out of the 10,000 possible options 9,800 were destined for the cutting-room floor.

That ratio alone confirms that this is not a comprehensive history how could it be? There are many more omissions than inclusions. But it is, we hope, a new way of looking at the world during a time of monumental change. It has been a privilege and a pleasure to create. We hope you enjoy reading it.

Marina Amaral & Dan Jones April 2018

Sometimes of course, digging proves fruitless. At this point the colourizer needs to make artistic choices, just as the historian uses his or her judgment. What might this have looked like? You follow your instinct and never pretend to know everything for sure.

symbols above any text paragraph that comes before the photo it describes. Otherwise, text without a hand symbol will always come after the photo it describes.

symbols above any text paragraph that comes before the photo it describes. Otherwise, text without a hand symbol will always come after the photo it describes.