Copyright 2015 by Kay Frydenborg

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file.

ISBN 978-0-544-17566-2

eISBN 978-0-544-55693-5

v1.0415

To all people living in cacao-growing regions, both in our own time and in the past, who sacrificed everything in the name of chocolate.

And to those who have found pleasure and comfort in a taste of the worlds most perfect food.

The Worlds

Most Perfect Food

Chemically speaking, chocolate really is the worlds most perfect food.

Michael Levin, nutritional researcher, as quoted in The Emperors of Chocolate, 2000

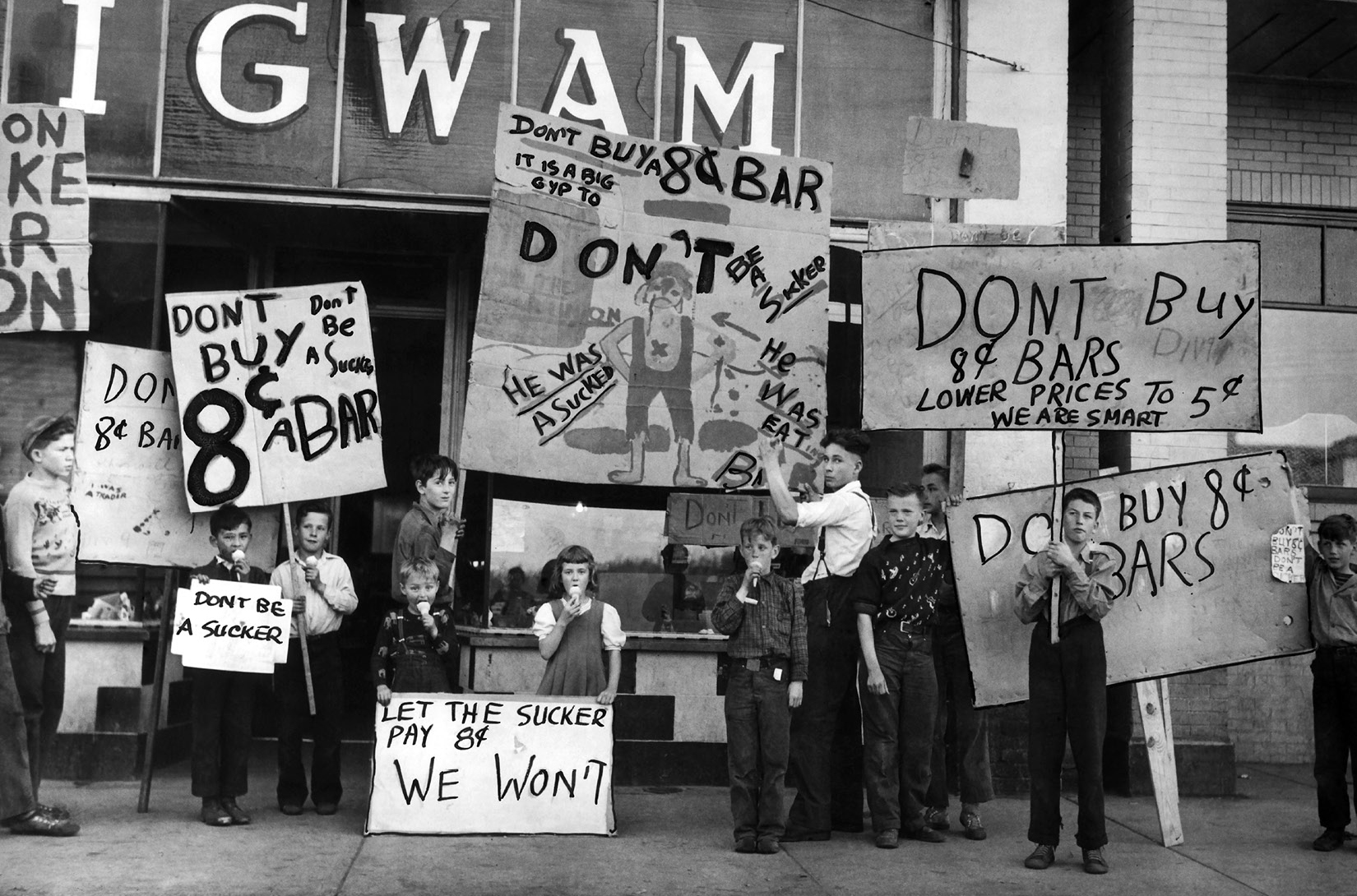

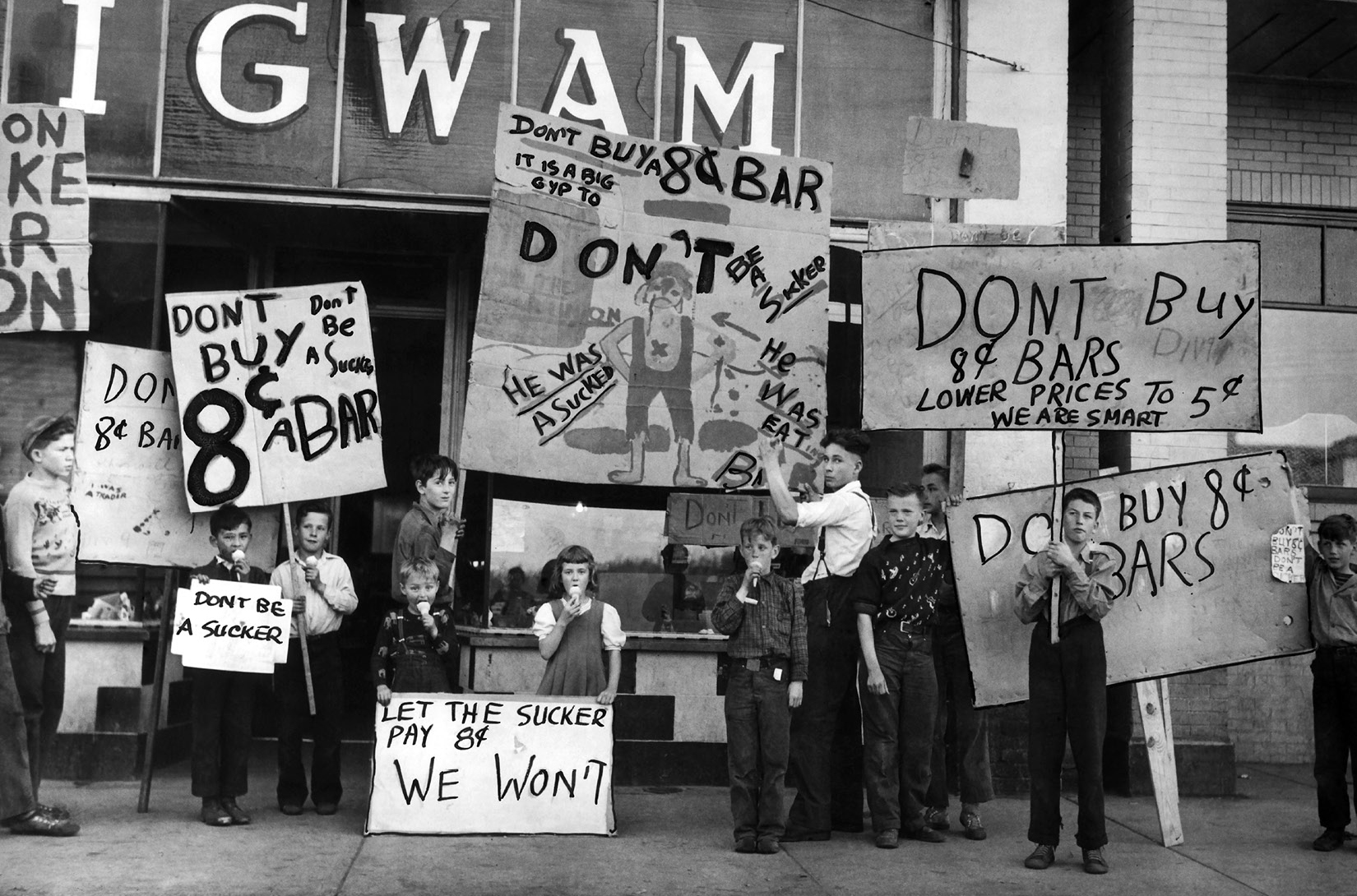

On April 25, 1947, four boys in the sleepy town of Ladysmith, British Columbia, on Canadas Vancouver Island, decided to take matters into their own hands. Theyd discovered that the spare change theyd set aside to buy their favorite chocolate bars from a local ice cream parlor called the Wigwam would no longer be enough to buy the bars. One member of the group, seventeen-year-old Parker Williams, had entered the shop in eager anticipation and had come out empty-handed. Overnight, the price of chocolate bars had risen from five cents to eight centsa 60 percent increase for a three-ounce bar. Parker could hardly believe his eyes. It was outrageous.

In 1947, children and teens walked picket lines to protest a sudden hike in the cost of chocolate bars.

The boys vowed to do something about it that very day. Theyd organize a strike! With the friends, classmates, and younger brothers and sisters they had recruited, they scrawled their objections with markers on cardboard. They chalked slogans all over Parkers old Buick, too, and later that day he drove this protest-banner-on-wheels slowly up and down the street in front of the Wigwam, while other kids hung off the sides of the car or marched behind. Lifting their signs high, a growing line of youthful militants snaked past shops and passersby, singing lyrics they had just composed:

We want a 5-cent chocolate bar.

8 cents is going too darn far

We want a 5-cent chocolate bar

Oh, we want a 5-cent bar!

World War II had come to an end, and nations around the globe were rebuilding their economies. In the West, free-market capitalism was rushing back after years of government-mandated wage and price freezesincluding a freeze on the price of chocolate. Parents were worried about rising prices too.

Most parents in Ladysmith supported their childrens protest effort. Many adult-led community groups also began helping out, printing signs and pledge cards, providing snacks for kids on the frontlines, and lending moral support. Chocolate bars, in 1947, seemed like a fundamental right.

Ladysmith was a small town and news traveled fast. Soon nearly every kid in town had joined the chocolate bar strike. A photographer from the local paper snapped a photo of the protesters circling in front of the Wigwam; the next day, kids across Canada began picketing their own corner stores.

What this country needs is a good 5-cent bar! said some of their signs. Candy is dandy, but 8 cents isnt handy!

On April 30, two hundred kids marched on British Columbias capitol building in Victoria and shut down all business in the city for a day because of chocolate. Similar actions were repeated in Burnaby, in Toronto, and on Ottawas Parliament Hill. The movement swept through the country. Police were called in to break up the crowds. More than three thousand kids signed pledge cards promising to boycott the sale of chocolate until the price returned to normal. Within days, sales of chocolate bars in Canada had dropped by a staggering 80 percent.

Candy companies, caught off-guard, defended the higher price. They, too, were struggling with postwar inflation. The cost of milk, sugar, and cocoa-processing labor had all risen with the lifting of government price controls.

The young protesters were unmoved by this logic. This was about freedom, prosperity, and fairness! It was simple. They wanted their chocolate bars; they deserved their chocolate bars. But they would boycott eight-cent bars. By raising their collective voices, they aimed to hold the line on runaway prices. They planned their biggest event yeta march on Torontofor May 3. But then the adult world of international and domestic politics, big business, and postwar paranoia intervened.

On the eve of the Toronto march, an anonymous source told a reporter at the Toronto Evening Telegram that the entire candy strike was being orchestrated by a pro-labor organization with alleged ties to the Communist Party, and the ultraconservative newspaper concluded, in print, that the childrens chocolate crusade was nothing more than a front for Communists in Moscow.

Communism was widely feared at that timemany in North America believed that Communists, called Reds for their supposed allegiance to the red Soviet flag, were planning to overthrow democracy.

Suddenly, formerly supportive organizations disowned the strike. Emotions were running high, but no one wanted to be seen as a Communist sympathizer. Parents forbade their children to participate further in the demonstrations. The strike fizzled out, and the price of a chocolate bar never returned to five cents. This was deeply disappointing to the kids, for whom communism was an abstract concept that had nothing to do with their spontaneous protest.

By the time U.K. chocolate maker Divine ended production of Dubble Bars in May 2014, more than 11,000 bars had been sold, contributing more than $162,000 to Fair Trade farmers and development programs, underscoring their slogan, Changing the World Chunk by Chunk.

But they werent ready to give up chocolate. Whether allowances were raised by sympathetic parents or extra chores were completed to earn the money, kids continued to buy their favorite bars. By 1947, life without chocolate had become unthinkablechocolate had already changed the world.

The truth is, the world has changed chocolate, too, in surprising ways. Its all part of the long, strange history of this remarkable food. In its original liquid, unsweetened form, it was a key element in the culture, diet, religious rituals, and economies of several major Mesoamerican civilizations for more than two thousand years before anyone in the Western world had ever heard of it, let alone tasted a drop.

It wasnt until August 15, 1502, during his fourth and last voyage to the Americas, that Christopher Columbus encountered a large dugout canoe near an island off the coast of what is now Honduras. It was filled with local goods intended for trade, including fine cotton garments, a variety of weapons, and copper bells. But perhaps the most valuable item was a large cache of cacao beans, which Columbus and his men had never seen before and mistook for almonds. Columbus directed his crew to seize the canoe from the Indians and retained their leader as his guide.

Later, Columbuss son Ferdinand described the encounter. He was struck by how much value the Native Americans placed on the strange-looking almonds. They seemed to hold these almonds at a great price, he wrote, for when they were brought on board ship together with their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all stooped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen.

Next page