1. Introduction

There is a popular refrain about the First World War: everything that could possibly be said has been said already. A quick glance at the military history shelves in any Australian bookstore would seem to offer superficial confirmation of this view. Scores of pages have been written about the mud, the trenches, and the barbed wire of France and Belgium, and, of course, scores more have been written about Gallipoli. But the ubiquity of such publications should not be mistaken for breadth of knowledge about the war. As the National Commission on the Commemoration of the Anzac Centenary suggests, despite the staggering amount of information available regarding Gallipoli, there is a corresponding lack of understanding about its history. If that applies to Gallipoli, one could reasonably expect the gaps in knowledge about other aspects of the war to be at least as great.

One factor that may have influenced this idea of nothing new to say is a saturation of what Australian military historian Jeffrey Grey has described as compartmentalised histories; histories that examine the minutiae of specific battles, leaders and experiences, often through a stridently national lens. Such studies are typically oversimplified, repetitive and clichd, and seem to dull the enthusiasm of people seeking to understand more about the complex nature of the First World War. However, the recent transnational turn has the potential to revitalise this history. Reconceptualisation of the war as a global conflict enables the foregrounding of multiple connections and contexts that bring to the surface experiences, perspectives and voices that are often marginalised in traditional compartmentalised accounts.

This approach is one that pre-eminent First World War scholars Hew Strachan, Keith Jeffery and Jay Winter have long enjoined others to put into practice. In the revised introduction to his landmark history of the war, which was republished in 2014 at the beginning of the centenary period, Strachan makes the very clear point that contemporary perceptions of the First World War do not reflect the diverse lived experience of the conflict: it is trench warfare, it is shaped by artillery and machine gun fire, it is wet and muddy, and it is overwhelmingly in Europeand disproportionately in Western Europe.

In Australia, several scholars have responded to this call to internationalise First World War history. For example, Joan Beaumonts 2013 book Broken Nation brings the Australian battlefield and home front experience of the war into a wider narrative sweep, while Peter Stanley and Vicken Babkenians pioneering study of the relationship between Australians and the Armenian genocide, Armenia, Australia and the Great War , focuses on the Australian response to this genocidal event in the Ottoman Empire and the resulting large-scale humanitarian crisis. These recent histories mark something of a departure from traditional Australian interpretations of the war, which have tended to be inward-looking and float free of any broader context. In the immediate post-war period Australian historians of the conflict, beginning with the official historian Charles Bean, focused primarily on the battlefield as they located within the soldiering experience a sense of national exceptionalism and distinctiveness. The next generation of scholars shifted focus to the home front, applying traditional labour history tools of analysis to the study of social conflict, economic disturbance and industrial unrest within the nation. This approach dominated Australian historiography until the rise of cultural history methodologies in the 1980s brought into the analytical frame themes such as grief and bereavement, trauma and memory, and commemoration. While these cultural histories broke new ground, they continued to examine the war in national isolation.

This collection builds on the recent work of scholars such as Beaumont, Stanley and Babkenian (among others) by teasing out Australian connections to the global First World War and situating them within an international context. The book maps out a broader, more nuanced canvas by considering how Australians engaged with the war overseas through military and volunteer service, and through the echoes and reverberations of international events at home. Such connections and engagements often turned on human mobilities, the crossing of boundariesphysical, racial and genderedand the transplanting and reshaping of cultural contexts. Through this localglobal framework, a diverse cast of historical actors comes into clear view: Indigenous Australians; foreign-born soldiers; prisoners of war (POWs); Red Cross volunteers and others. At the same time, varied cultural forms of the war and its memory that transcend the traditional written canon of historical practicein this case, literature, commemorative patterns and documentary filmare able to be explored.

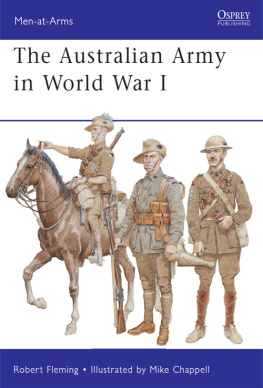

Drawing on the work of a varied group of contributors, the book is conceived as four thematic sections. The first is focused on rethinking the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Karen Agutter explores the experiences of foreign-born soldiers (from allied, neutral and enemy nations) to reveal the multinational nature of Australias fighting force, and the ways in which the problems foreign-born soldiers encountered were representative of attitudes towards the other in wider Australian society. Meleah Hampton offers operational insights into the conduct of the AIF in the last year of the war. Her chapter examines the Australians participation in, and contribution to, the systematic application of a wide range of weaponry and tactics as part of the integrated British effort to advance, and eventually succeed, on the Western Front in 1918.

In Part II, contributors make explicit the crossing of boundaries as Australian military personnel and volunteers were faced with the complexities of a global war. Kate Ariotti explores the cross-cultural encounters of Australian POWs in the Ottoman Empire, and argues that the prisoners interacted with those they encountered in captivity according to pre-war Australian conceptions of racial and cultural hierarchies. In doing so, her chapter contributes to a growing understanding of the experience of captivity as a reflection of the multinational nature of the war. Victoria Haskins focuses on several Australian army nurses at a hospital in Deolali, India, and documents their response to charges of inappropriate relations with patients and hospital staff. Her analysis reveals how, by inhabiting a confined cross-cultural space, anxieties about Australian womens intimate contact with non-white men were intensified by the First World War. The theme of womens experience of the war is continued by Melanie Oppenheimer in a chapter assessing how patriotic Australian women engaged with the conflicteither at home or overseasthrough the Red Cross. Oppenheimer argues that by taking up a range of opportunities, both voluntary and paid, these women were able to feel more actively connected to the imperial war effort.

The third part of the collection explores the impact of the war on Australians at home, including its historiography. In the first of these chapters, Frank Bongiorno interweaves the many and varied threads of Australian home front histories of the First World War. He argues that recent histories have increasingly brought labour and cultural history strands into dialogue with each other, particularly as scholars have sought to link the battlefield with the home front. The other contributions to this thematic section can be read as responses to Bongiornos identification of a renovated approach to home front history insofar as they each discuss the resonances and ripples of overseas events and their implications for the domestic context. The point of departure for Stephanie James chapter is the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, the British response, and the reverberations of this watershed event in Australia. James begins with the well-documented arrest and internment of seven Irish-Australians accused of links to the radical Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1918. Through extensive use of government security agency files, she examines the less familiar story of ordinary Irish-Australians whose contacts and communications suggest a wider network of potentially subversive activity aimed at resisting wartime Australias pro-British and anti-Irish atmosphere. Indigenous connections with the First World War have been the subject of increasing attention from historians in recent years, but so far the emphasis has been predominantly on battlefront experiences. Sam Furphys chapter broadens the lens by considering the effects of the war on Aboriginal peoples at home, focusing on a wide range of themes: employment; government policy; imperial loyalty; repatriation and soldier settlement. Lastly, Bart Ziino offers a reassessment of Australian home front history through analysis of private sentiment. Ziino claims that traditional studies of the Australian home front centred on division and unrest have been less interested in how Australiansso distant from the main theatres of the warmaintained their commitment to total war for the duration of the conflict. He argues that examining the mobilisation of human and emotional resources helps to locate Australian civilian commitment within the same processes that sustained the war at its centre.