The Calling of History

Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of Truth

DIPESH CHAKRABARTY

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Dipesh Chakrabarty is the Lawrence A. Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor of History and South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. He is the author of several books, including Habitations of Modernity: Essays in the Wake of Subaltern Studies, also published by the University of Chicago Press.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10044-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10045-6 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24024-4 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226240244.001.0001

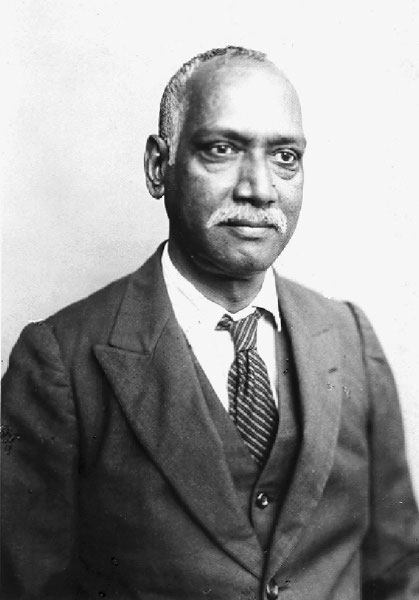

Illustration on page ii: Jadunath Sarkar (ca. 1926). Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Archives, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. Used with permission.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh, author.

The calling of history : Sir Jadunath Sarkar and his empire of truth / Dipesh Chakrabarty.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-226-10044-9 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-226-10045-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-226-24024-4 (e-book) 1. Sarkar, Jadunath, Sir, 18701958. 2. HistoriansIndiaBiography. 3. IndiaHistoriography. 4. Historiography. I. Title.

DS435.7.S26C53 2015

907.202dc23

[B]

2014041928

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To those who showed me the way:

the late Barun De and Asok Sen in Calcutta;

Anthony Low and Ranajit Guha in Canberra; the late Greg Dening in Melbourne

And to Rochona, who shares the journey every day.

Contents

DCL, Deccan College Library

GOI, Government of India

IHRC PROCEEDINGS, Indian Historical Records Commission, Proceedings of the Meetings

IHRC RETROSPECT, Indian Historical Records Commission: A Retrospect, 19191948

IRD, Imperial Record Department

JSP, Jadunath Sarkar Papers

NAI, National Archives of India, Delhi

NL, National Library, Calcutta

SP, Sardesai Papers (Kamshet), digital copies in the authors personal collection

Rhetoric is the dialectic of the public square, the agora, in contrast to the dialectic of the lyceum or the academy.

CARL SCHMITT, The Nomos of the Earth

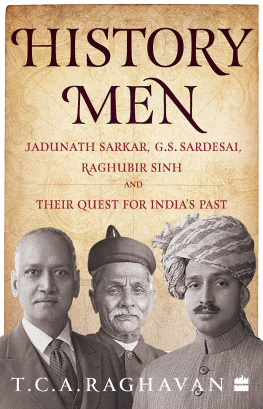

The book in your hands, dear reader, comes out of a chance encounter in the library. I would not be the first person to report an experience of stumbling upon material that gave rise to a research project. A gifted New Historicist might even make something theoretical of what may be called librarial luck. But let me be more modest and just recall, in a gesture of gratitude to the very existence of physical libraries in this digital age, how one day sometime in the mid-1990s and as someone new to the riches of the Regenstein Library at the University of Chicago, I came across a book with an appendix excerpting about 250 letters exchanged between two Indian historians, Sir Jadunath Sarkar (18701958) and Rao Bahadur Govindrao Sakharam Sardesai (18651959). The letters covered the years from 1907 to 1952. The book was a collection of essays edited by Dr. Hari Ram Gupta and published from Punjab in 1958 as a tribute to Sir Jadunath in the final year of his life. As a physical object, the book was not particularly attractive. The font seemed too large for serious prose, the paper coarse, the general appearance ordinary, and the printing uneven. But Jadunath Sarkar was once a name every educated Indian knew. A Bengali by birth, he was easily the most highly regarded Indian historian, and he had a very strong public presence in late-colonial India. Sardesai, his correspondent, was similarly a well-known and respected historian, from what is now the state of Maharashtra in India. Browsing these excerpted letters in the library, I vaguely sensed their importance. Here were two of Indias pioneering historians writing to each other for decades about issues crucial to historical research, and yet I had not seen any significant discussion of these letters by scholars of South Asia. I felt fortunate in having stumbled upon them. It is only now, after I have finished writing this book, that I have some sense of exactly how fortunate I was. I now know that the publication of Hari Ram Guptas book was dogged by financial uncertainty. And I would not even know this factoid except through a second stroke of luck in October 2012, when some colleagues and I discovered, in a heap of waste paper in the locked-up residence of Sardesai in Kamshet (near Poona), some letters from another historian, Dr. Raghubir Singh, a princely historian from what used to be the native state of Malwa and a student of Sarkars. In a couple of these letters, Dr. Singh spoke of the financial uncertainty that once threatened the publication of these excerpts. Dr. Gupta did not know until near the very end, it now seems, that there would be money available to pay the expenses of including a large appendix containing these extracts. Finding Sardesais house was an adventure in itself, which I briefly describe in chapter 2.

There was, however, nothing particularly serendipitous or surprising about why I found the excerpted letters arresting. Barring the prominent exceptions of Damodar Dharmanand Kosambi (19071966) and Ranajit Guha (1923) in the twentieth century, there are not many known instances of Indian historians discussing, in a truly sustained and original manner, methodological issues involved in the production of historical knowledge. History has been an important subject in India from the colonial times and is among the most successfulalong with economics and anthropology (often folded into sociology in India)of the social sciences that have flourished in the country since the attainment of political independence in 1947. India has been blessed with many gifted historians. Yet on questions pertaining to methods or epistemology fundamental to the disciplineand I should make it clear that I am not speaking of historiography hereeven the best Indian historians have usually been content to let Western savants make pronouncements from time to time on what history was, while they, the Indian scholars, busied themselves with producing learned and good histories that, though attentive no doubt to global methodological debates, did not aim to contribute in any fundamental way to the issues being debated.

It was therefore intriguing to come across letters between two prominent Indian historiansone of them recognized generally as one of the greatest modern historians that India has produceddiscussing in private, and with passion and fury sustained over a period spanning the entire first half of the twentieth century, questions of critical importance to the very procedures that make history an academic discipline: What did it mean to do research in history? How would one weigh historical evidence? What would be a defining distinction between facts and the raw materials of history? How might one go about collecting sources for writing history in a context where no effective public archives were available? How would one explain the historical absence of public archives in India and make a case for building them? And other related questions. The letters did not produce any new philosophical or methodological insights as such, but the unflagging energy, intensity, and interest with which Sarkar and Sardesai pursued these questions was impressive. They were, moreover, not asking the questions in an abstract vein; it was clear that the questions were integral to their own research and to the debates they were actually engaged in with their contemporaries in India. Given the absence of any vigorous discussions of these issues in the scholarly world of Indian history today, I felt curious to understand why they seemed so urgent to these Indian historians in the first half of the twentieth century, what provisional answers the two fashioned for themselves, and why. The larger narrative of this book addresses that initial and immediate curiosity that Guptas book sparked in me as I stood riveted to those epistolary excerpts in the immense and overwhelming presence of books in the famed Regenstein Library.