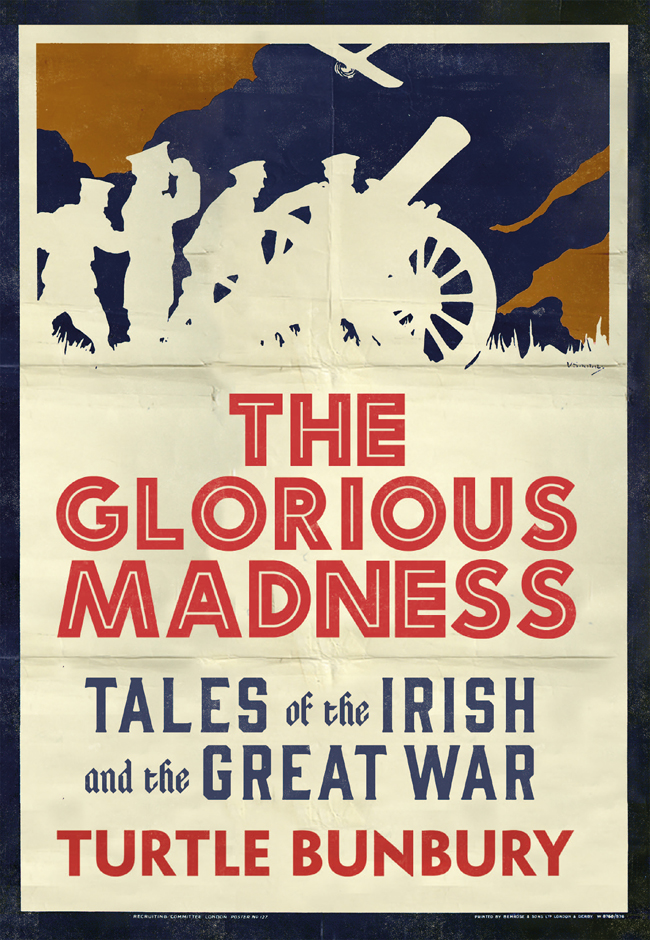

THE

GLORIOUS

MADNESS

TALES of the IRISH

and the GREAT WAR

TURTLE BUNBURY

Gill & Macmillan

DEDICATION

Every morning, as I set off to work on this book, my two small daughters would pounce upon me like clockwork and ask: Are you writing about dead people again, Daddy? Such is the lot of a historian! But war is not an easy subject to share in a family home. Not unlike those who returned home from the front lines, I was inclined to keep my thoughts to myself for the most part. Therefore, I dedicate this book to those with whom I live my beautiful wife Ally, my gorgeous daughters, Jemima and Bay for keeping our home full of laughter and merriment and love while I wrote and dreamed of grim and ghastly war.

The book is also for Alan Appleby Drew, Guy Finlay, Bobby Finlay and all the other souls who lived and died during the time of the Great War.

CONTENTS

To every life that God hath given, he hath allotted a work the fulfilment of that work comes naturally, and its proper accomplishment should form the sole ambition of that life.

ALAN APPLEBY DREW (18841915)

WASTE

Waste of Muscle, waste of Brain,

Waste of Patience, waste of Pain,

Waste of Manhood, waste of Health,

Waste of Beauty, waste of Wealth,

Waste of Blood, and waste of Tears,

Waste of Youths most precious years,

Waste of ways the Saints have trod,

Waste of Glory, waste of God War!

REV GEOFFREY STUDDERT KENNEDY,

AKA WOODBINE WILLIE (1919)

INTRODUCTION

MY HAIRBRUSH ONCE BELONGED TO A MAN CALLED ALAN APPLEBY DREW, AN UNCLE OF MY paternal grandmother, who was working as a teacher at Mostyn House School in Cheshire when the Great War broke out. Alan was a man who liked to sing and entertain. He had travelled a good deal and spent a few years in Shanghai. His father was on the Scottish team who took on England in the worlds first rugby international. Alan evidently felt sufficiently Scottish to join the Cameronians, aka the Scottish Rifles. Lieutenant AA Drew arrived on the Western Front in February 1915 and lasted four weeks. The 31-year-old was killed at Neuve-Chapelle, alongside most of his fellow officers from the Cameronians. I found his grave in the Royal Irish Rifles cemetery at Laventie and I thanked him for his hairbrush. After his death, his distraught family gifted a carillon of 31 bells to Mostyn House, one bell for every year of his life. When that school closed a few years ago, the bells were offered to Charterhouse in Surrey, where Alan had been at school. Considering that Alan was one of a staggering 687 past pupils from Charterhouse who died in the war, the school was very keen to take the bells. And so it was that on a sunny afternoon in May 2014, I stood beneath a belfry at Charterhouse, alongside my father and my oldest brother, listening to the clanging melodies as AA Drews carillon rang anew.

My maternal grandmother also lost two uncles in the war. Guy Finlay and his younger brother Bobby grew up at Corkagh House near Clondalkin, County Dublin. Their father was Lieutenant Colonel of the 5th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and, not surprisingly, both sons joined the regiment. So too did their eldest brother, Harry, who succumbed to dysentery in the Anglo-Boer War. Bobby was killed in Flanders during a failed attempt to capture the German trenches at Aubers Ridge in May 1915. Fourteen months later, Guy fell at the Somme, caught out by the German counter-attack at Bazentin Ridge.

Three years ago, my brother and I went to find our great-great-uncles graves on the Western Front. Before we left, I dashed into the woods of Corkagh Park on a whim, seeking something from the old family home that I might place on the Finlay brothers graves, should we find them. Rather pathetically, the best I could come up with were two leaves from a majestic old horse chestnut tree that they had perhaps played beneath as boys. The bodies of Guy and Bobby were never found, so they had no graves. However, I found their names on the memorial walls at Ploegsteert and Pozires and I wedged the chestnut leaves alongside them.

It was exceptionally moving to find Alan Appleby Drews grave and the names of the two Finlay brothers. But it was at the cemetery in Tyne Cot in Flanders that the immensity of the war overwhelmed me. I walked alone down a path through line after line of those proud white headstones, with a wall blocking the view to my left. I thought I might have become immune to all the death by then, but any jauntiness in my stride vanished and I found myself walking ever slower until I ground to a halt just at the point where the wall beside me ended. And then I turned my eyes to the left and I slumped. Behind the wall, the field of graves was replicated again and again as far as I could see, like the saddest dream ever dreamt. Endless rows of white upright slabs, 12,000 all told, framed at one end by the Memorial to the Missing upon which were written the names of another 35,000 whose bodies were never identified.

Most veterans of the Great War felt compelled to submerge their experiences in grim silence, creating an emotional void that would torment their wives and their children to such an extent that I think the repercussions of that war will be felt by unknowing generations for many decades to come.

For those who returned to Ireland after the war, the horror of their experience was magnified by the realisation that everything they fought for amounted to naught and that anyone who thought otherwise was no longer welcome. Although many of those who won independence for the Irish Free State had formerly served in His Majestys forces, there were powerful elements within the new order that would oblige the country at large to throw an unforgiving eye on ex-servicemen of the British Empire. In time, the hostility became amnesia and the Ireland of my youth in the late 20th century seemed to have a history in which the only war the Irish ever fought was for freedom from Britannias rule.

Tom Kettle was one of Irelands most brilliant nationalist politicians when the war erupted. He chose to fight because he believed the Kaisers army would destroy the very fabric of Europe. And yet he was also intuitively aware of how the truth could coil upon itself. In the wake of the Easter Rising, he wrote: Pearse and the others will go down in history as heroes, and I will be just a bloody English officer. When the Irish President Michael D Higgins addressed the Houses of Parliament in Westminster in the spring of 2014, he spoke of Kettle specifically, and acknowledged all of the other Irish men and women who served. It was another coming-of-age moment for Ireland, an end to decades of silent schizophrenia.

There are no clear-cut figures as to how many Irish actually fought. By the time you combine all the Irish or half-Irish who served in the British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and US armies, there was probably more than a quarter of a million. Tempers tend to rise during the guessing game of how many Irish-born actually died but a figure of between 35,000 and 40,000 seems to be increasingly accepted. The Irish war dead remain almost entirely forgotten in most of the towns and villages from whence they came. In the small town of Tullow, County Carlow, where I wrote this book, at least 63 men perished in the war but I suspect that very few people in the town have ever heard of those 63 dead men.