FRONTLINE BOOKS, LONDON

Bayonets and Scimitars: Arms, Armies and Mercenaries, 17001789

This edition published in 2013 by Frontline Books, an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

Copyright William Urban, 2013

Foreword copyright Dennis Showalter, 2013

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-84832-711-5

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47383-087-5

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47382-971-8

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47383-029-5

The right of William Urban to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior

written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in

relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for

damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

and the Library of Congress

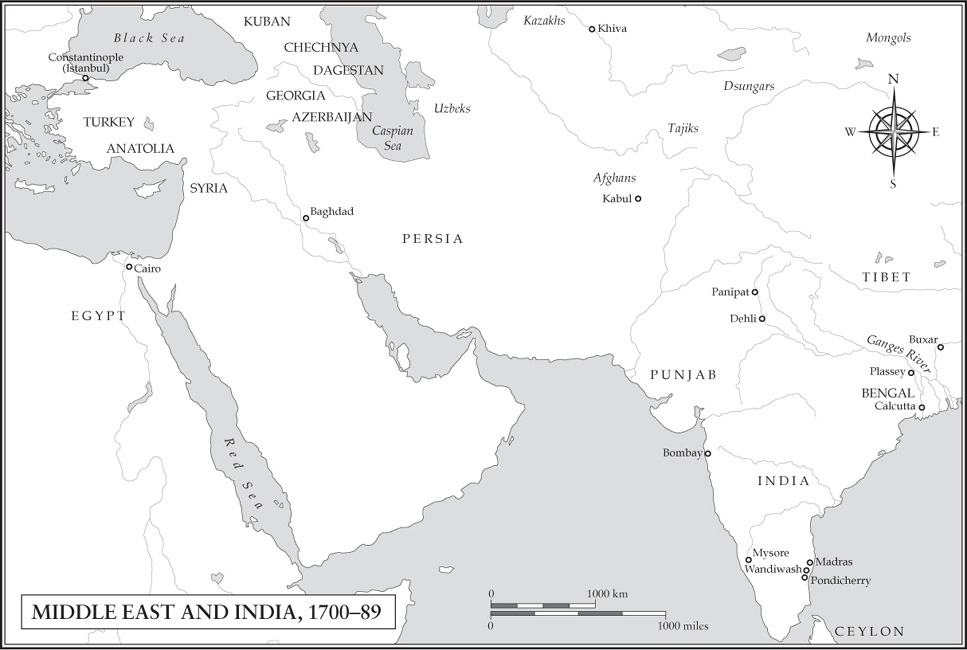

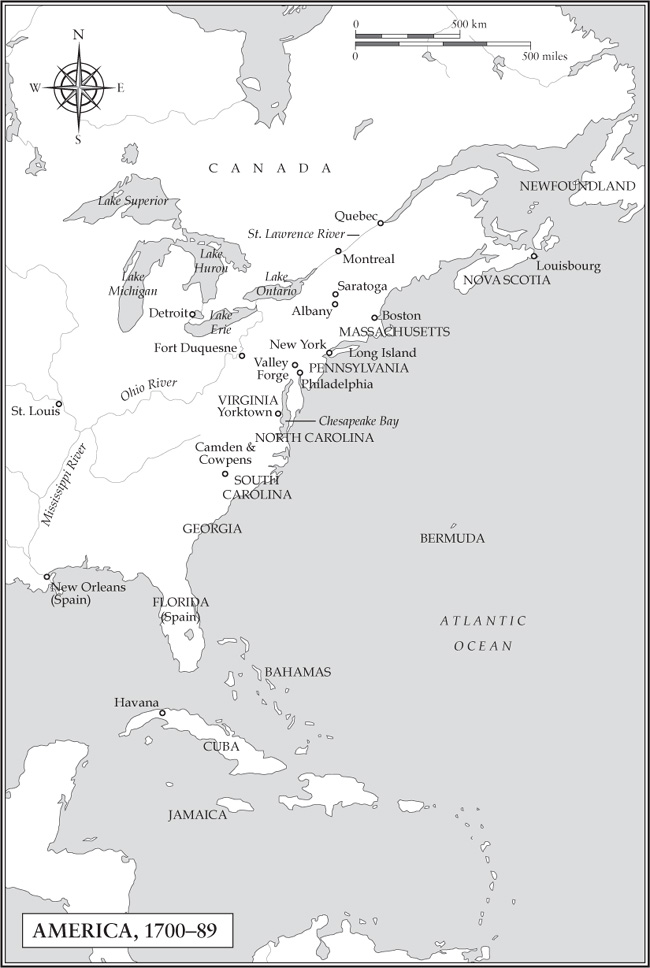

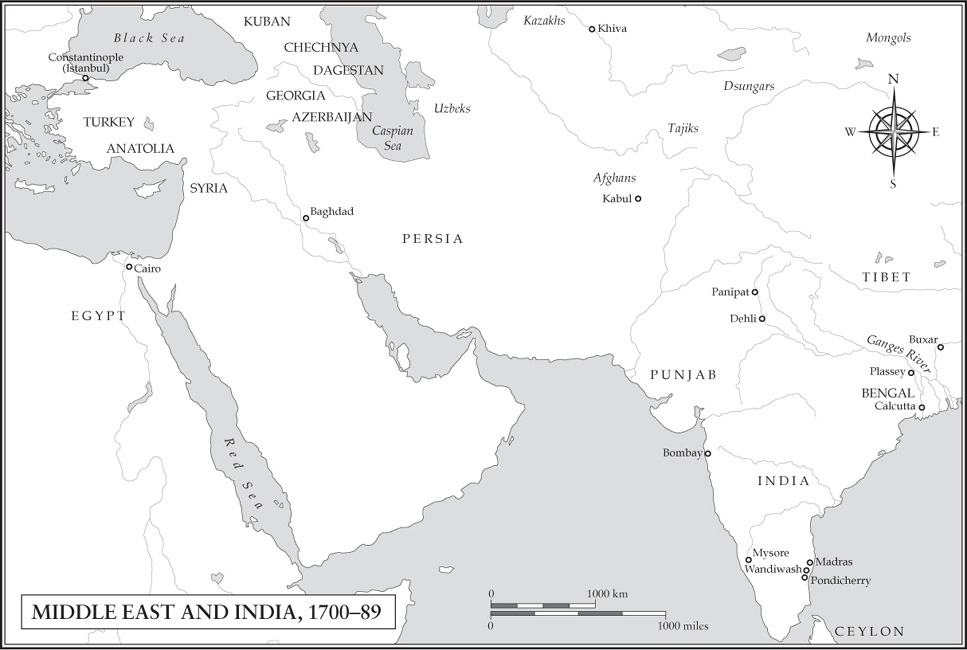

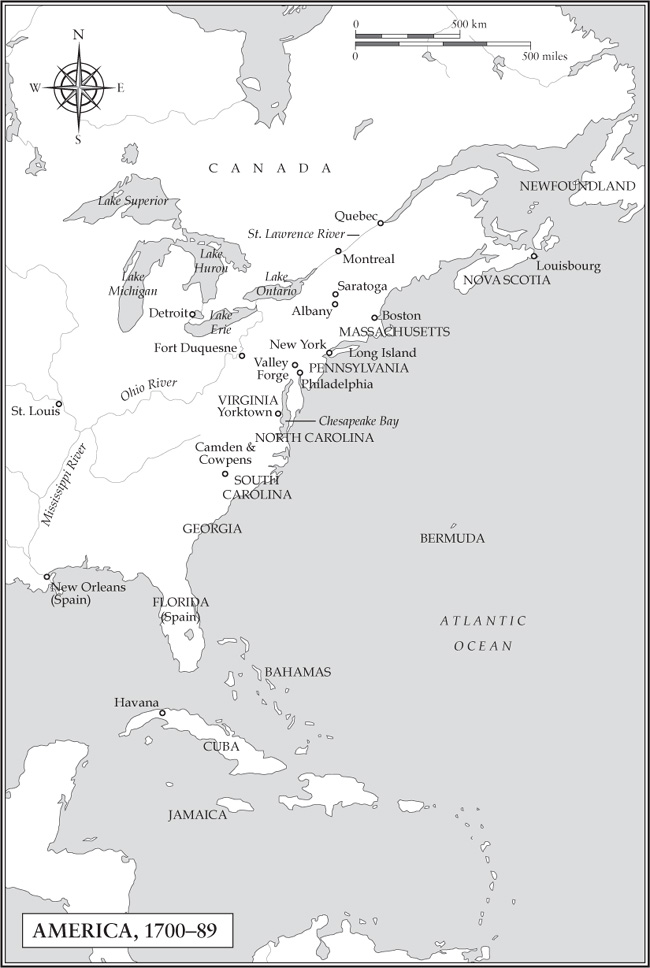

Maps created by Alex Swanston, Pen and Sword mapping department

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com,

email

or write to us at the above address.

Typeset by JCS Publishing Services Ltd, www.jcs-publishing.co.uk

Printed and Bound by CPI Group (UK), Croydon, CR0 4YY

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Plates

Foreword

This is the third volume in a trilogy that is an extended reflection on the changing nature of early modern war. Its ideas and concepts reflect not only the previous volumes, but Urbans long and distinguished career as a scholar of warfare on Europes northeastern margins. His focus is the gradual development, broadly defined and at all levels of war-making, of mercenaries into professionals in eighteenth-century Europe. The basis of that transformation was a military-technical revolution: the simultaneous development at the centurys beginning of the flintlock musket and the socket bayonet. The combination was a weapons system that increased infantrys fighting power to a point where, for the first time since the Roman legions, Europes battlefields were dominated and defined by a single arm of service, with a single kind of soldier able to employ both fire and shock with maximum effect.

The result was a tactical symmetry that fostered battlefield gridlock. Armies imitated each other so closely that eighteenth-century war at the sharp end became a matter of endurance rather than performance. Traditional warrior traits found little place in combat whose intensity made increasing demands on a soldiers capacity to stand firm: to control fear without the anodyne of activity. Campaigns as well, particularly in the relatively barren expanses of East Prussia and central Europe, were exercises in survival, with the pleasures of rapine and pillage severely limited. Optimal use of the musket and bayonet, moreover, depended on extensive, comprehensively synergised training. Cadenced marching, keeping in step to the beat of a drum, was a complex learned skill not to be taken for granted. Eighteenth-century drill was designed in part to condition the individual soldier to collective activity by inculcating automatic physical responses: loading by the numbers, moving according to orders. Drill, however, was more than a means of inculcating reflex behaviour. It was a survival mechanism. A clumsy or self-willed man in a musket-and-bayonet formation could initiate disorder, and that made him a potentially fatal liability. A recruit unable or unwilling to accept that concept was likely to be the subject of unwelcome attention from his fellow soldiers as well as the non-commissioned officers.

Neither conditioned reflex nor self-interested co-operation were enough to hold men in ranks under fire. A soldiers relationship to the system any system he serves differs essentially from all others because it involves a central commitment to dying, as opposed to accepting death as a possible byproduct of other activities like fighting fires or enforcing laws. Much of the time for most soldiers the death clause is inactive. An individual can spend thirty honourable years in any uniform and face only collateral risks such as training accidents. Even in war the commitment is not absolute. Armies incorporate a collective sense of what it is legitimate to expect under given circumstances. As casualty lists mount, soldiers are increasingly likely to begin scrutinising the moral fine print in their agreements, written and unwritten, with the state and society they fight for. Specifically, the infantry on which an eighteenth-century army depended for its effectiveness, depended in its turn on fighting spirit as well as on formal discipline. Compulsion in its varied forms might keep men from running. It could not make them fight. More precisely, it could not keep them fighting in battles that as the century progressed came to resemble nothing so much as feeding two candles into a blowtorch and seeing which melted first.

The seventeenth-century soldier had identified himself in terms of individuality. Becoming a soldier involved being able to carry a sword, to wear outrageous clothing, to swagger among the women in ways denied the peasant or artisan. The eighteenth century witnessed the development of armies as communities. To an extent that development was overlooked as long as historians focused on the socio-economic process. This small-m Marxism stressed military service as based on economic marginalisation, specifically unemployment and underemployment, whether structural or intermittent. Hunger as the best recruiting sergeant became a scholarly meme. Recent research takes an alternative perspective: the search for behaviours cultural origins and manifestations. Boredom, a desire for new experiences and fresh horizons, is emerging as a fundamental source of recruits. Change offered prospects for a different servitude, even for the relatively limited numbers conscripted in various forms. Europes armies in short were, by and large, composed of men willing to fight for something other than the immediate defence of their own homes.

That did not necessarily mean desire for a completely random life. As intrastate conflict became a permanent feature of international politics the period from 1689 to 1815 is regularly described as the second Hundred Years War states found it more economical and more functional to maintain permanent armies as opposed to raising them ad hoc. Soldiers were correspondingly able to find a literal home in the army, serving for years in stable environments, with guaranteed employment, under material and social conditions that more or less paralleled those they could reasonably expect as civilians. British army courts martial, for example, carefully regarded procedure and evidence, with military punishments in general no harsher than those the civil codes provided for similar offences. Prussias uniforms were among the best in Europe. Its soldiers medical care was superior to anything normally available to craftsmen and peasants. Its superannuated veterans had good chance of government employment or public maintenance in a garrison company.

Next page