Medieval Mercenaries

A Greenhill Book

Published in 2006 by Greenhill Books, Lionel Leventhal Limited

www.greenhillbooks.com

This paperback edition published in 2015 by

Frontline Books

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

For more information on our books, please visit

or write to us at the above address.

Copyright William Urban, 2006

The right of William Urban to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-854-9

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-857-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-855-6

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-856-3

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

CONTENTS

by Terry Jones

ILLUSTRATIONS

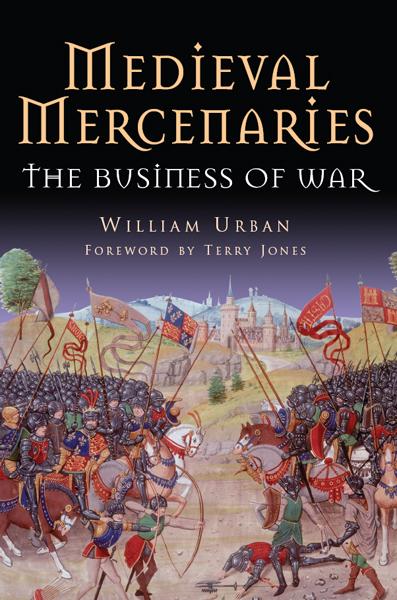

Endpapers: Flemish School, Predella with the Taking of Jerusalem, Ghent Museum voor Schone Kunsten 1990, Photo Scala, Florence

FOREWORD

In 1980, I wrote a little about the mercenary armies of the fourteenth century and how their proliferation throughout Europe was regarded by contemporaries as a catastrophe on a par with the Great Plague itself. It seemed then as big a threat to civilisation as the Atom Bomb does to us today: a Sword of Damocles hanging over us all a genie that has been let out of the bottle and that can never be put back in.

Well, I can only say that I wish Id had this book back in 1980.

Bill Urbans Medieval Mercenaries puts the events of the fourteenth century into a vivid historical context. He provides an astonishingly clear overview of the whole subject of mercenaries and he does so with tremendous authority and wit.

It makes a thrilling read.

Starting with the professional armies of Rome, he traces the rise of mercenary troops in the tenth and eleventh centuries, until their dominance of the battlefield during the Hundred Years War. He writes amusingly about the way Renaissance Italians turned the business of war into a minor art form, realising that both victory and defeat were equally unwelcome to the professional soldier: defeat bringing death and victory unemployment.

Bill Urban also provides a review of the literary treatment of mercenaries from Chaucer to Mark Twains A Connecticut Yankee At The Court Of King Arthur and Conan Doyles The White Company .

His conclusion is that though mercenaries seem like the problem they are, in fact, merely a symptom. And I would agree with that.

However, I also feel that the real business of war is less to do with the institution of professionalised armies and more to do with those who employ them. It is true that, in the fourteenth century, the ordinary professional soldiers got out of hand, forming themselves into freelance armies during periods of peace, and bringing death, destruction and mayhem to large swathes of Europe.

But in England, by the late fourteenth century, the real perpetrators of war were not the common soldiers, but the barons. Men like Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, and Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, needed warfare because their only hopes of gaining wealth and expanding their retinues lay in prosecuting the war with France. The ruin, death and destruction that this brought upon the civilian population meant nothing to such men, just so long as they profited from the chaos. To these two must be added Richard, Earl of Arundel, who although wealthy enough himself not to need to go to war, seems to have been of such a bellicose nature that warfare was his natural preoccupation.

These were the men whom the French writer and crusade activist, Philippe de Mzires, described as great Boars, black and bristling, sons of that mighty Black Boar who so many times destroyed the vineyards of France. ( Le Songe du Vieil Pelerin I, 117)

The barons adamantly opposed Richard IIs policy of peace between France and England out of their own self-interest and in despite of the interests of the people. Perhaps little wonder that Philippe should characterise King Richard as a miraculous white boar working for the common good.

Today the situation seems pretty similar except that there is no miraculous white boar on the horizon as yet. The hawkish barons have been replaced by the revolving door between the militaryindustrial complex and the policymakers the precise mechanism that President Eisenhower warned about in his departing speech to the nation. In the twenty-first century war has been firmly and publicly espoused by administrations on both sides of the Atlantic.

As always, there are pretexts put forward for waging war didnt Attila the Hun claim he was invading Europe in order to rescue a damsel in distress? She happened to be the Emperors sister Honoria, who had smuggled out her ring to Attila and begged him to rescue her from a life of boredom!

Today other pretexts are found that are no less flimsy, but who cares as long as there is profit to be made out of warfare? It is not the mercenaries themselves, however, who propagate a state of perpetual conflict, but their employers the politicians connected to the construction, servicing and arms industries, who stand to make handsome bonuses and future incomes out of a thriving war economy. The deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent people count as little to these people as the misery of the peasantry did to the barons of the fourteenth century.

As long as there are people and companies who make vast profits out of war, war will continue to plague our world. But we should not blame the mercenaries and the professional soldiers they are merely the messengers of death.

Terry Jones, 2006

PREFACE

IT IS TIME for a survey of medieval mercenaries that describes how they created in Juhan Kreems elegant phrase the business of war. Although textbooks often pass over mercenaries, they were present throughout the medieval era. Moreover, the textbooks and surveys have neither the personal details that make narrative history interesting and exciting, nor analyses of what mercenaries actually did. These deficiencies are part of what this book intends to address.