Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Michael Dekker

All rights reserved

Front cover, top, left to right: Wikimedia Commons, Maine Historical Society, Bowdoin College Museum of Art; bottom: Maine Historical Society.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.574.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015937275

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.775.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For my infinitely patient and understanding family. Kathy, maybe now our schedules and routines will return to normal. Thanks for all you have done to support me in this endeavor. Whit, we have some play time to catch up on. Ellie, thanks for our evening television sessions. They were just what I needed.

Contents

Preface

James Skoglund, my middle school social studies teacher, planted the seed of this book many years ago. Growing up in Thomaston and developing an early interest in history, I was naturally receptive to Mr. Skoglunds intimation that Thomaston had been a battleground among the English, the French and the Indians. Having found an old bayonet in the barn and an arrowhead in the garden as a young boy, my imagination was primed and my interest piqued. Twenty-five years later, I took up reenacting as a hobby, portraying a soldier on the Maine frontier during the French and Indian War. At the time, I knew Massachusetts had built forts along the Kennebec River and provided soldiers to garrison the outposts scattered across the region. While attending a battle reenactment at Fort Ticonderoga, an unknown fellow reenactor asked me Why do you portray a soldier in Maine? Nothing happened there. I distinctly remember replying, That may be true, but the men manning cold, isolated outposts deserve to be remembered in the same way as those who participated in the grand, memorable events of the war. Feeling comfortable with the answer, the question itself left me feeling unsettled. The memory of Mr. Skoglunds words years before gave me pause to consider that perhaps more happened in Maine during the period than I or most people realized.

Combing the records of local historical societies, town histories, the collections of the Maine Historical Society and the Massachusetts Archives, I sought a more complete understanding of the French and Indian War here in Maine. Initially, I began cataloguing incidents and events pertaining to King Georges War (174548) and the French and Indian War (175563). The cursory and incomplete list quickly topped 125 examples of armed encounters between white and native people who called Maine home. It became readily apparent that both the question asked of me at Ticonderoga and my answer were ill founded. Maine was not a quiet backwater on the periphery of the struggle for North America. Rather, Maine, and the midcoast region in particular, was caught up in its own related but distinctly local struggle between competing cultures.

All history occurs within a context. As it was, I began my inquiry at the end of a historic epoch. King Georges War and the French and Indian War were the final chapters in a long, sad story of war, dependence, disease and displacement. The tragedy began with the very first exchanges between Europeans and the native people of eastern North America and would continue in Maine for the next 150 years. Staggering from the effects of pandemic disease, social disintegration and intertribal warfare, the indigenous inhabitants of Maine emerged from the first half of the seventeenth century to find themselves besieged by the effects of exploitative trade and the pressures of relentless land acquisition by ever-increasing numbers of European settlers. The result was decades of nearly endless conflict and violence. As one historian of the period sardonically commented, Every once and awhile peace broke out on the Maine frontier. It is impossible to estimate the number of lives lost or calculate the effects of suffering endured by the people of Maine during the darkest period of the regions history. What began as an inquiry based on historic curiosity evolved into an eye-opening journey that has become this book.

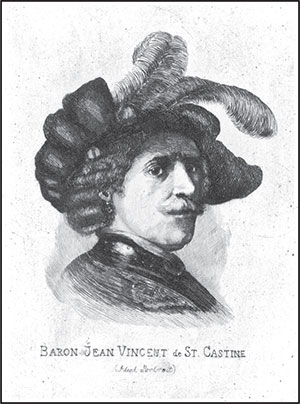

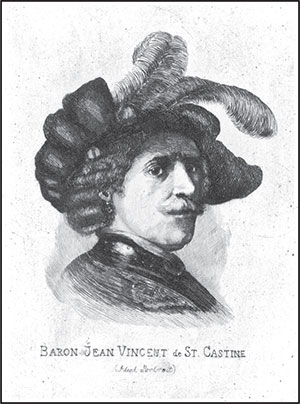

Admittedly, this is not a definitive work on the French and Indian Wars in Maine. The focus of this book is on the midcoast region from the eastern portions of Casco Bay to the Penobscot River. The midcoast and Kennebec Valley was the cauldron in which resentment, misunderstanding and tensions between the native people and their white neighbors simmered and boiled over in waves of repeated violence, ultimately engulfing all of Maine. The stories of attacks against the communities and outposts of southern Maine during King Philips War (167578), King Williams War (168899) and Queen Annes War (170313) could fill the pages of a book in their own right. Likewise, several topics of interest and historical relevance have been omitted in an effort to streamline this narrative. The story of Jean Vincent dAbbadie de St. Castin or Baron St.-Castin is one such omission. Castin was a French military officer residing at Pentagoet (Castine) offering the Penobscot trade goods, political council and military leadership. Castin assimilated into the culture of the Penobscot people and married the daughter of the powerful sagamore Madockawando. Carrying on the family legacy, Castin the Younger, Baron St.-Castins son and Madockawandos grandson, later wielded considerable influence among the Penobscot as a military and political leader.

Baron St.-Castin. Castin was a French military officer, trader and councilor among the Penobscot people. Like many early Acadians, Castin embraced many aspects of the native culture and intermarried with the local population. Castin married the daughter of Madockawando, a chief sagamore of the Penobscot people. Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

The role of the Mohawk and the Iroquois Confederacy in the diplomatic exchanges between Massachusetts and the eastern tribes has also been glossed over in this work. Years of bitter warfare between the Iroquois and the Abenaki during the beaver wars resulted in Abenaki submission to the covenant chain, a web of peace understandings among the Iroquois, the English and the Algonquian people of the Northeast. Throughout the period of the French and Indian Wars in Maine, Mohawk and Iroquois delegates regularly met with the eastern tribes on behalf of Massachusetts to remind them of their commitment to the covenant chain and cajole or strong-arm them into submission. Despite their traditional fear of the Iroquois, the Mohawk in particular, the native people of Maine routinely dismissed their entreaties and threats. With no particular stakes in the unfolding situation on the Maine frontier, the Iroquois, believing they had in good faith fulfilled their obligations to Massachusetts under the covenant chain, refrained from taking up the hatchet, as they threatened, against the eastern tribes.

Next page