Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Ellen Drury Whitehurst

For Leslie Reingold

A NOTE TO READERS

Eighteenth-century written English is notoriously cluttered with confounding punctuation, capitalized nouns erupting in the middle of sentences, and multiple spellings of the same word, all of which did not become standardized until comparatively recently.

Throughout the following text we have endeavored to present to readers the voluminous writings of our characters precisely as they themselves put those words to paper.

PROLOGUE

H is troops had never seen George Washington so angry. His Excellency, as most of them called him, had always been the most composed soldier on the battlefield. But on this sweltering late June morning in 1778 the commander in chief of the Continental Army could not mask his fury.

He reined in his great white charger and trembled with rage. Rising in his stirrups, he towered over his second in command Gen. Charles Lee, the man he had charged with leading the attack. What is the meaning of this, sir? I demand to know the meaning of this disorder and confusion!

Nearly two years to the day since the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the fate of the American cause lay uncertain, all because the officer cowering before Washington had panicked and ordered a premature retreat. In a sense Washington blamed himself. General Lee had not wanted the assignment in the first place. He should have followed his instincts and left the Marquis de Lafayette in command. Lafayette had been by his side at Valley Forge, had witnessed and absorbed the esprit of the troops who had survived the horrors of that deadly winter. Valley Forge had been the crucible they had all come through together, the very reason the forces of the nascent United States were now poised to alter the course of the revolution. And was that same army now about to be destroyed because of one mans incompetence and lack of faith?

Charles Lee, dust-covered and dazed, gazed up at his superior. His eyes were dull, and his face wore the gray pallor of defeat. Sir? he stammered. Sir? The words were nearly unintelligible. He could find no others. Washington dismissed him and spurred his own horse forward.

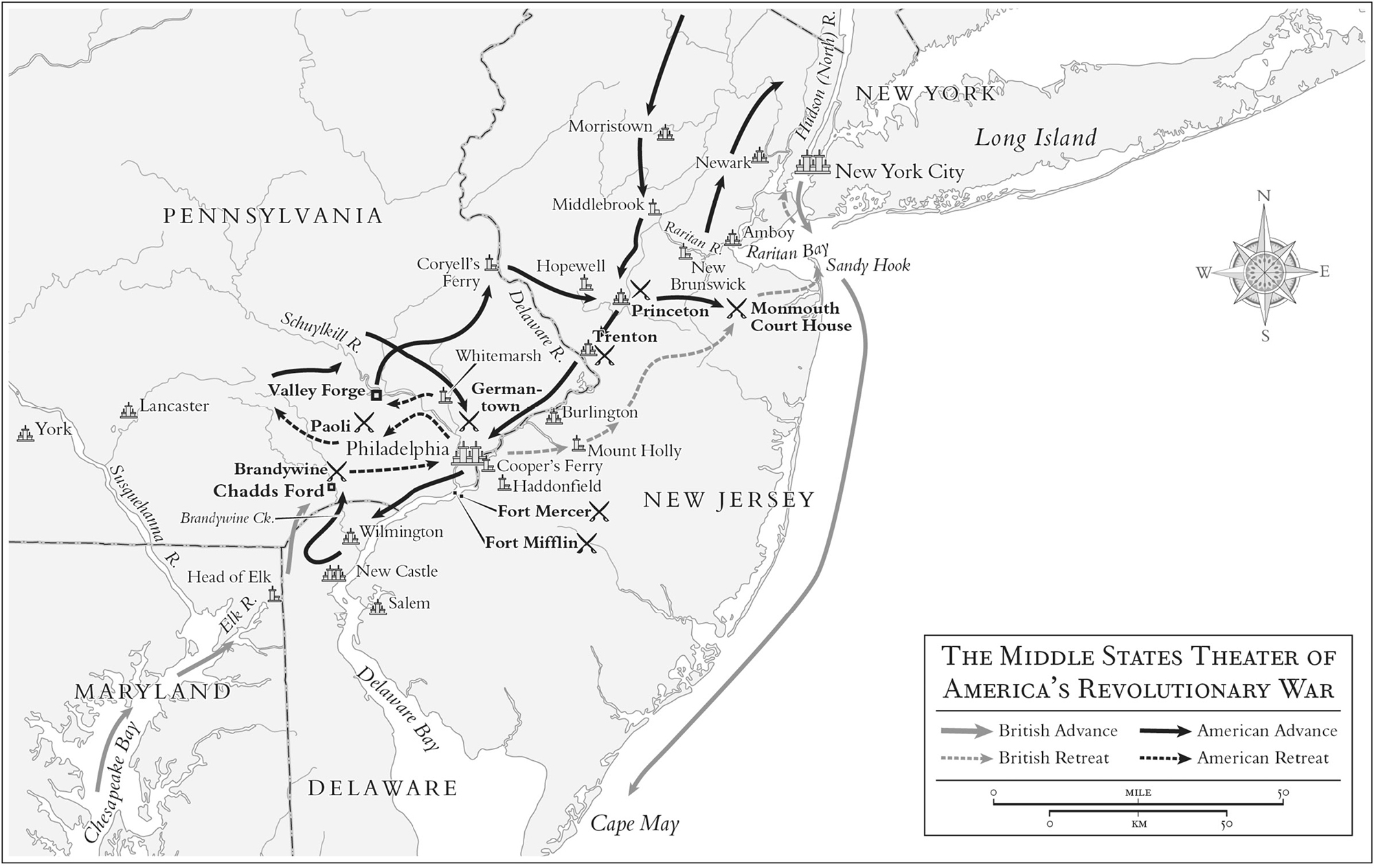

As hed approached the rolling green hills and swampy culverts surrounding the small New Jersey village of Monmouth Court House, an astonished Washington had demanded of each brigade and regimental commander he encountered to know why his unit was falling back. None could give a coherent answer, other than that Gen. Lee had ordered it. Now, as Washington galloped up and down the lines before his weary and bedraggled soldiery, the determination on his face was evident. Those who witnessed it would never forget it. A gallant example animating his forces, one veteran artillery officer later recalled.

Less than a mile to the east, 10,000 elite British troops had shed their packs, fixed bayonets, and were driving hard in counterattack. The British generals Henry Clinton and Charles Cornwallis could hardly believe their good fortune. After 12 months of a stalemated Philadelphia campaign, here was an opportunity to crush the colonial rebellion. If past was prologue, the mere sight of an endless wall of British cold steel would send the Continental rabble fleeing in disarray. A glorious rout would restore the transatlantic equilibrium. King George III would be ecstatic.

Washington knew otherwise. The hellish winter at Valley Forge had taught him so. He and his army had not endured the mud and blood of that winter encampment only to be turned back now. Half hidden in the smoke and cinders of battle, he ascended a rise and gathered about him the remnants of his exhausted army. It was the critical juncture of the war, and the tall Virginian exuded a sense of urgency and inspiration. Thirsty men who had wilted in the hundred-degree heat rose to their feet in anticipation.

Will you fight? Washington cried. Will you fight? The survivors of Valley Forge responded with three thunderous cheers that reverberated across the ridgeline. Lafayette, riding with Alexander Hamilton beside the commander in chief, was overwhelmed. His presence, the young Frenchman wrote, seemed to arrest fate with a single glance.

The skies darkened with cannon shot just as Washington raised his sword and pointed it toward the approaching sea of red. He was about to spur his horse again when Hamilton jumped from his own steed and shouted, We are betrayed, and the moment has arrived when every true friend of America and her cause must be ready to die in their defense!

Washington, his aristocratic reserve regained, replied in a calm voice. Colonel Hamilton, he said, get back on your horse.

PART I

The Enemy were routed in the greatest Confusion several Miles, we passd thro their Encampments & took some pieces of Cannon, in short we were flatterd with every appearance of a most glorious & decisive Action when to my great surprize Our Men began to give way, which when the Line was once broke became pretty General & could not with our utmost Exertions be prevented & the only thing left was to draw them off in the best manner we could.

GEORGE WASHINGTON TO GEN. ISRAEL PUTNAM, OCTOBER 8, 1777

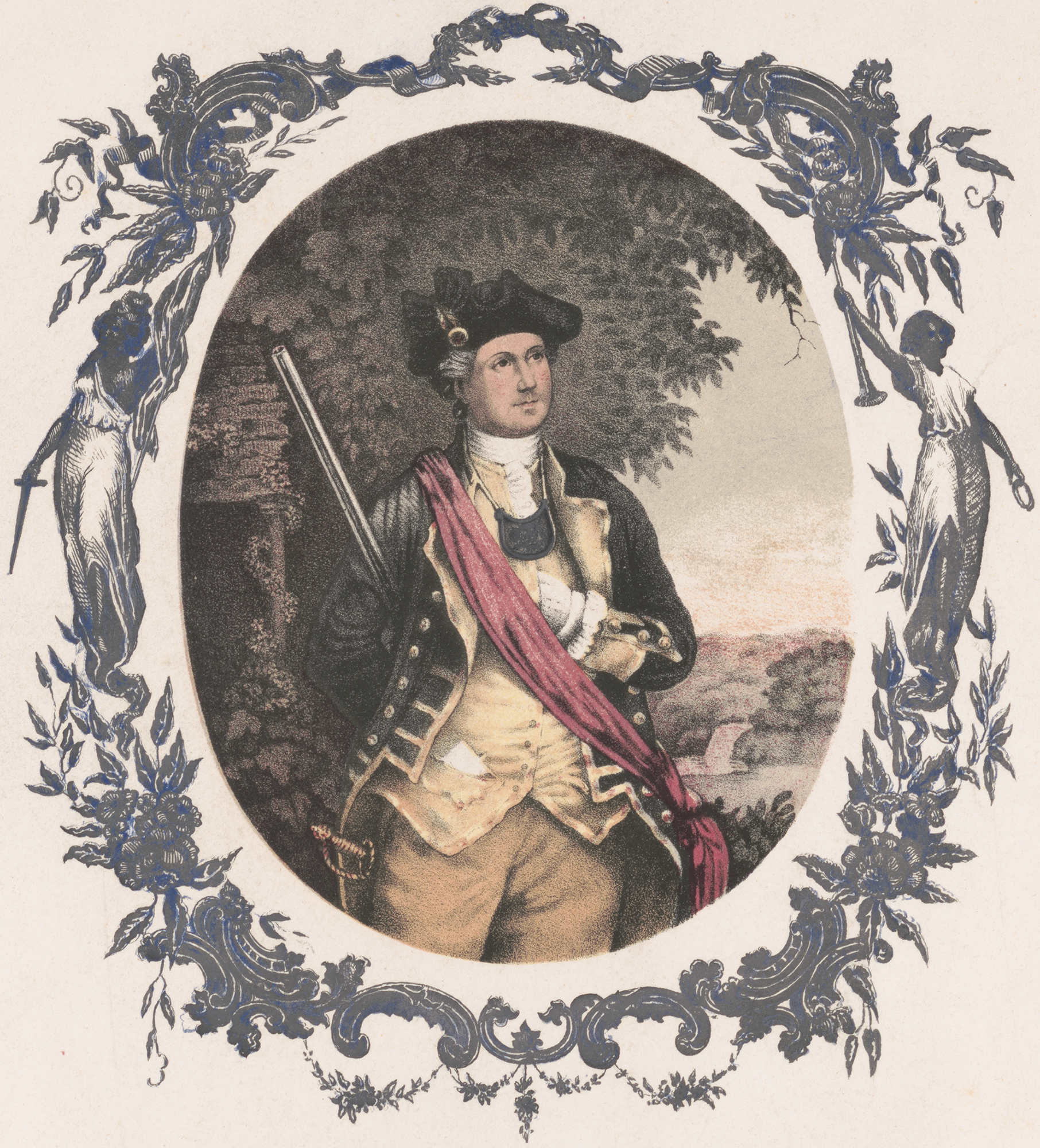

George Washingtons experiencesboth good and badas a young officer in the Virginia militia fighting alongside British forces in the French and Indian War served him well as commander of the American forces.

ONE

A SPRIG OF GREEN

T hey marched in parade formation through the heart of Philadelphia, 12,000 strong. Down Front Street and up Chestnut Street they came, the heroes of Trenton and Princeton, the survivors of Long Island and Harlem Heights and White Plains, and they constituted a panoply foreshadowing the diversity that would define a future nation. The Grand Army, they were called: Irishmen, Germans, and Poles; French and disaffected Brits and Scots; a company of African American freemen, all now newly minted Americans. A multiplicity of interests, as James Madison would call them, forging a distinct national identity. Every man wore a sprig of greenery affixed to his hat or woven through his hair. It was a symbol of hope and victory.