Leisure & Pleasure

For my sister, Sarah, with love

COVER AND FULL -PAGE PHOTOGRAPHS

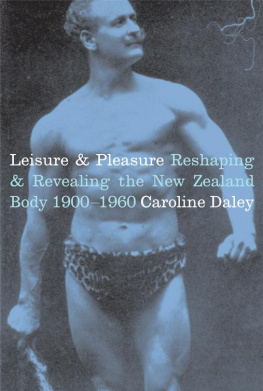

FRONT COVER

Taken in Melbourne just before his only New Zealand tour, Eugen Sandow poses for his public. Reproduced in his book Body-Building, or Man in the Making: How to Become Healthy and Strong, London, 1904.

BACK COVER

Dulcie Deamer, physical culturist and nudist, made headlines in 1908 when, at the age of sixteen, she wrote about the sex problem and won a short story contest in the Sydney monthly magazine, the Lone Hand. She soon left her home in Featherston, eventually settling in Sydney where she continued to advocate the need to do your daily dozen and to exercise in the nude. Health and Physical Culture, 1 October 1929. Mitchell Library, Sydney.

PAGE

Eugen Sandows 14-inch chest expansion. This photograph is credited to the Auckland photographer Herman John Schmidt, though it is unlikely that it is a Schmidt original. G-1837-1/1, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

PAGE

Crowds gathered outside Wellingtons James Smiths department store to look at the mannequin dummy dressed in a bikini. The sign on the window reads The Battle of the French Fashion Banned Bathing Suit. Sun Soakers. James Smith Ltd Collection, PAColl-3332-3-2, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

PAGE

E. H. Garland as Greek god, c.1919. Like most men who displayed their bodies at this time, Garland was smooth and hairless, his flesh mimicking the marble of classical statues. G-13963-1/1, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Contents

In the late 1990s, when I began this project, I expected to write a journal article on strongman Eugen Sandows tour of New Zealand. But as I researched that tour, and found out more about the father of modern body building, my interest grew. In large part this was due to the work of Sandows biographer, David Chapman. David has been incredibly generous in sharing his knowledge about Sandow and the wider physical culture movement of the early twentieth century with me, and in opening up his archive to me. I thank him for all of his support and help, and hope he enjoys Leisure & Pleasure.

Doing the research for this book has been very pleasurable indeed, in no small part because of the expert assistance I have received from librarians and archivists. At the University of Auckland I would like to give particular thanks to the incredibly helpful and efficient team in the interloans section, and Giles Margetts in the microtext room. Down town, David Verran, Kirstie Ross and the staff of Special Collections at Auckland City Libraries were wonderful. Patrick Jackson, at the Auckland City Council Archives, aided my research in many ways. In Wellington I enjoyed the usual high standards of assistance and advice at the National Library and the Alexander Turnbull Library, and although my time at Archives New Zealand was sometimes frustrating, it was ultimately rewarding. Jo-Anne Smith at Canterbury Museum, the New Zealand room staff at Christchurch City Libraries and the librarians at the Macmillan Brown Library at the University of Canterbury were always helpful, as were the staff at the Hocken Library in Dunedin. In Sydney I would like to thank the librarians at the State Library of New South Wales and the Mitchell and Dixson libraries. I would also like to acknowledge the warm welcome and assistance I received at the American Nudist Research Library in Kissimmee, Florida.

The picture research for this project was most enjoyable, and I am grateful to all of the libraries which provided me with images. I would especially like to thank Auckland City Libraries, the Alexander Turnbull Library, and the Hocken for waiving reproduction fees.

Needless to say, I could not have undertaken these research trips, nor ordered the many photographs illustrating this book, without financial assistance. I am most grateful to the University of Auckland for providing me with two Research Grants and awarding me short leave with a grant-in-aid, as I worked on this book.

Alongside the help of librarians, archivists and my university, researching this book was pleasurable thanks to the support and help of friends and family. For putting up with me, and putting me up, I thank Angela Pearce in Wellington, Doreen and John Endacott and Philippa Mein Smith and Richard Tremewan in Christchurch, and Pauline and the late Joe Ryland in Florida. For listening to me talk about the book and offering me advice and references, I thank Judith Binney, Peter Boston, Barbara Brookes, Malcolm Campbell, Tim Frank, Helen Laurenson, Charlotte Macdonald, Malcolm MacLean, Dot Page, Bobby Petersen, Kim Phillips, Barry Reay, Grant Rodwell, Greg Ryan, Terry Ward, and Matt Wilcox. In the course of this project I have given conference papers throughout New Zealand and Australia on various aspects of the modern body at play. I would like to thank the conference organisers and participants for listening and responding to my work. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank my immediate family for the interest they have shown in this project, and the support and love they always give me and my work. Ive dedicated this book to my sister, Sarah, with whom I spend much of my leisure time. Thank you for always being there.

If researching the book was pleasure, writing it was pure hard work. The task was lightened by the wise counsel of Elizabeth Caffin, the Director of Auckland University Press. As always, Elizabeth has been incredibly supportive of this project and of me, and I am most grateful. Working with the award-winning team at AUP is always pleasurable. I would like to thank Katrina Duncan for making my words look good, Annie Irving for keeping the administration under control, and Christine OBrien for her marketing expertise. I would also like to acknowledge AUPs anonymous reader, for being so favourably disposed towards the book, Sarah Maxey for her beautiful cover design, and the History Group at the Ministry for Culture and Heritage for awarding the book a publication subsidy.

Three other people deserve special mention (and medals) for the support they offered me as I wrote up my research. Two of my colleagues read my entire manuscript and offered careful, helpful suggestions. I can only apologise to Deborah Montgomerie and Joe Zizek for not following through on more of their recommendations. They are wonderful friends and very dear to me. Finally, I want to thank my partner and best friend, David Braddon-Mitchell, for listening to me, reading my work, offering a non-historians perspective on the text, and making me dinner. Your love and support mean the world to me.

August 2003

In 1955 Daisy Martin, a farmers wife in Nelson, received an interesting Christmas present: a bronze statue of a naked strongman, holding a barbell. The sculpture had belonged to her father, Harold Robinson. As a young Lancashire lad Harold had been a seemingly hopeless cripple, but at the age of 21, walking with the aid of a stick, he sought help from the famed physical culturist, Eugen Sandow. Despite having one shortened leg, under Sandows expert guidance Harold became well-known as a cyclist and swimmer. Indeed, it was claimed that he was Sandows star pupil, and was given the statue in recognition of his success.

By the beginning of the twentieth century Sandow was an international superstar. His well-developed body and his system of exercises had gained him attention throughout the British Empire and the United States. He was famous enough to have his own magazine, and to hold The Great Competition, a search for the most perfectly developed man. To reward those who followed his system, gold, silver and bronze statuettes of Sandow were given to the first, second and third place-getters in the contest. Harold had raised his daughters as Sandow girls, physical culturists who reshaped their bodies and were proud to reveal the results for all to see.